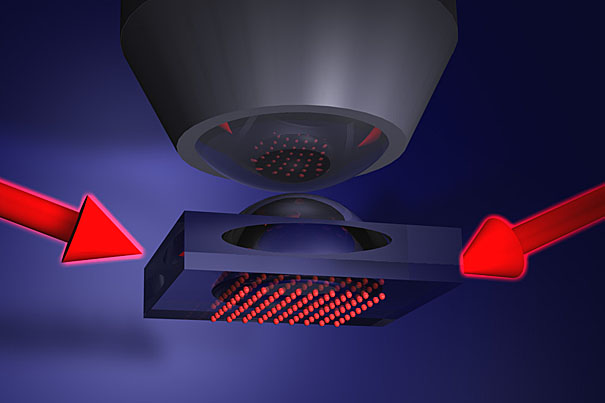

A sketch of a quantum gas microscope that images individual ultracold atoms in an optical lattice. It’s part of scientists’ efforts to use ultracold quantum gases to understand and develop novel quantum materials.

Markus Greiner/Harvard University

Quantum gas microscope created

Offers glimpse of quirky ultracold atoms

Physicists at Harvard University have created a quantum gas microscope that can be used to observe single atoms at temperatures so low the particles follow the rules of quantum mechanics, behaving in bizarre ways.

The work, published this week in the journal Nature, represents the first time scientists have detected single atoms in a crystalline structure made solely of light, called a Bose Hubbard optical lattice. It’s part of scientists’ efforts to use ultracold quantum gases to understand and develop novel quantum materials.

“Ultracold atoms in optical lattices can be used as a model to help understand the physics behind superconductivity or quantum magnetism, for example,” says senior author Markus Greiner, an assistant professor of physics at Harvard and an affiliate of the Harvard-MIT Center for Ultracold Atoms. “We expect that our technique, which bridges the gap between earlier microscopic and macroscopic approaches to the study of quantum systems, will help in quantum simulations of condensed matter systems, and also find applications in quantum information processing.”

The quantum gas microscope developed by Greiner and his colleagues is a high-resolution device capable of viewing single atoms – in this case, atoms of rubidium – occupying individual, closely spaced lattice sites. The rubidium atoms are cooled to just 5 billionths of a degree above absolute zero (-273 degrees Celsius).

“At such low temperatures, atoms follow the rules of quantum mechanics, causing them to behave in very unexpected ways,” explains first author Waseem S. Bakr, a graduate student in Harvard’s Department of Physics. “Quantum mechanics allows atoms to quickly tunnel around within the lattice, move around with no resistance, and even be ‘delocalized’ over the entire lattice. With our microscope we can individually observe tens of thousands of atoms working together to perform these amazing feats.”

In their paper, Bakr, Greiner, and colleagues present images of single rubidium atoms confined to an optical lattice created through projections of a laser-generated holographic pattern. The neighboring rubidium atoms are just 640 nanometers apart, allowing them to quickly tunnel their way through the lattice.

Confining a quantum gas – such as a Bose-Einstein condensate – in such an optically generated lattice creates a system that can be used to model complex phenomena in condensed matter physics, such as superfluidity. Until now, only the bulk properties of such systems could be studied, but the new microscope’s ability to detect arrays of thousands of single atoms gives scientists what amounts to a new workshop for tinkering with the fundamental properties of matter, making it possible to study these simulated systems in much more detail, and possibly also forming the basis of a single-site readout system for quantum computation.

“There are many unsolved questions regarding quantum materials, such as high-temperature superconductors that lose all electrical resistance if they are cooled to moderate temperatures,” Greiner says. “We hope this ultracold atom model system can provide answers to some of these important questions, paving the way for creating novel quantum materials with as-yet unknown properties.”

Greiner’s co-authors on the Nature paper are Waseem S. Bakr, Jonathon I. Gillen, Amy Peng, and Simon Foelling, all of Harvard’s Department of Physics and the Harvard-MIT Center for Ultracold Atoms. Their work was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Army Research Office, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.