Women on the move

Schlesinger Library highlights women’s adventure writing in exhibit open through Feb. 26

Cornelia James Cannon, an 1899 graduate of Radcliffe College and a longtime Cambridge resident, set off with her sister on an automobile camping trip in the summer of 1917.

“Our plan is to leave our homes, our eight young children, our social and domestic responsibilities, and sally forth to see the world, as free lances and comrades of the road,” she wrote later. “A Ford, a tent, a camp stove, and the world is ours for the taking.”

Cannon’s account, “A Middle-Aged Adventure,” is wry and defiant. (“Our consciences were wrenched at the thought of our careless irresponsibility — for about a mile,” she observed.) It was never published, but is now available through a new digital project at Harvard, “Travel Writing, Spectacle and World History.” (The exhibit is on view through Feb. 26 in the Schlesinger Library’s first floor exhibit area during regular library hours.)

The project, accessible through HOLLIS to Harvard students and researchers, collects hundreds of travel accounts by women. The earliest is an 1818 letter describing a family wedding, the start of a nine-year sojourn to England. The latest is a 1972 account of a trip to China.

Along with manuscripts like Cannon’s, there are diaries, sketchbooks, photographs, letters, watercolors, and ephemera, including cruise ship menus and old passports.

The digital archive, which opened in November, was assembled from collections at the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America. The library’s extensive archives, begun in 1943, go well beyond travel writing. But a lot of such writing, evocative of women’s history, is contained in 3,200 collections of family papers, institutional archives, and manuscripts.

The Schlesinger also has set out in its first-floor gallery an exhibit of artifacts called “To Know the Whole World,” which will be on display through Feb. 26.

Cannon (1876-1969), a novelist who traveled the world well into her 80s, is represented in part by hand-colored sketches from her 1929 “Art Awheel in Italy,” an account of a three-month trip by Cannon, her four daughters, and an aunt. (The Italians were surprised to see women drivers.)

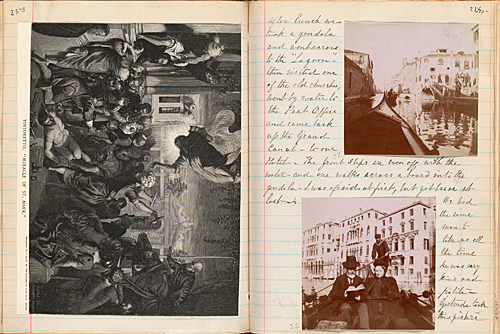

In the exhibit, there is also a travel diary recounting a seven-month tour of Europe by Sarah Shurtleff, who grew up in a wealthy Boston family. The diary, from 1898 to 1899, is a handsome pastiche of handwritten documents, photographs, and printed material.

“Part of my delight in the travel project is seeing the artistic output of women,” said Marilyn Dunn, the Schlesinger’s executive director. Dunn co-authored an introductory essay on the Web site with Ellen Shea, head of public services at the Schlesinger.

The women travelers in the collection display a breadth of time, class, and geography. The writers include Mary Adams Abbott, Chloe Owings, Rowena Morse, Rosamund Thaxter, and Catherine Filene Shouses (who wrote hair-raising accounts of early air travel). All are travel writers you otherwise would not know about.

One of Dunn’s favorites is Tabitha Moffett Brown, a Missouri widow who in 1846 set off on a harrowing wagon trip across prairies and mountains. After facing wolves, Indian attacks, starvation, and deep snow, she arrived in the Oregon Territory with just 6 cents. “In our extremity,” she wrote, “tears could avail nothing.”

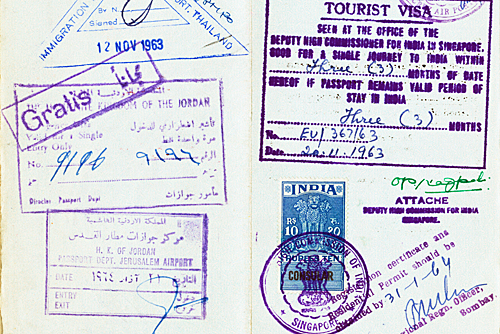

Like the digital collection, the library exhibit reveals the literary, the artistic, and the odd. In one glass case, a passport stretches accordion-style for several feet. It belonged to Edna Rankin McKinnon (1893-1978), a pioneering advocate of birth control whose papers the Schlesinger holds.

Cannon was an early birth control advocate too. The Schlesinger’s collection of travel writing reveals threads of feminist thought. After all, it is drawn from papers that had wider intent, writings and artifacts that in sum illustrate and document a sweep of interests: reproductive health, women’s rights, home economics, sexuality, fashion, war, family life, social justice, politics, and leisure.

“While we are a women’s-history repository,” said Dunn, “there is no end of topics.”

The wider topics are accessible, since digital collections are searchable. That too is a form of modern travel, on the back of a computer mouse.

The ease of digital travel is helpful to researchers. “Once a scholar breaks through the initial avalanche, the quality and depth of the material is excellent,” Katherine Stebbins McCaffrey said of the digital archives. “I found things I never would have otherwise.”

She is a history and literature lecturer at Harvard who teaches “Americans Abroad,” a freshman seminar on travel writing. She plans to have her class visit the exhibit soon.

Digital collections allow scholars to share sources and insights more easily, said McCaffrey. For students, the online collections are not a replacement for visiting the archive, but they are an attractive bridge to it.

The travel-writing archive was digitized in collaboration with Adam Matthew Digital. The British-based company digitizes collections at libraries around the world, and then offers them for sale as teaching and research aids. The for-profit path is one model of getting the Schlesinger archives “into the digital arena,” said Dunn. The library is also exploring grants to fund this kind of work.

A for-profit model is acceptable for some collections, but not others, said Dunn. The suffrage collection, for instance, would be better digitized as an open-source archive, available “at no cost,” she said, “for the public good.”

Following that open-access model will be the Schlesinger’s collected papers of Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860-1935), a writer, editor, commercial artist, and social reformer. She is best remembered for “Herland,” a 1915 utopian novel that imagines a peaceful isolated society of women, and for “The Yellow Wallpaper,” an 1892 short story regarded as an early feminist classic. Gilman’s papers will be digitized and available next year, in celebration of the 150th anniversary of her birth.

‘Travel Writing, Spectacle and World History’

Shurtleff travel diary, 1898-1899

By the late 19th century, it was fashionable for many upper-class women to undertake grand tours of Europe. As a member of a prominent Boston family, Sarah Shurtleff traveled extensively, including several trips to Europe. This diary covers a seven-month tour of England, France, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, and Germany. Shurtleff used photographs and printed material from the places she visited to create detailed, illustrated accounts of her travels. Credit: Nichols-Shurtleff Family Papers

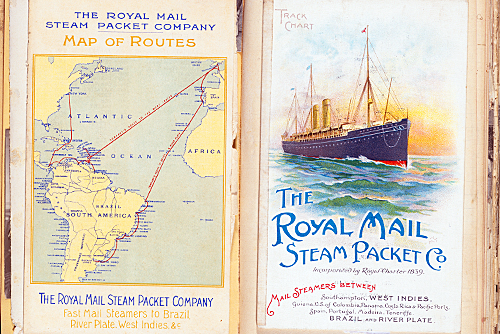

Royal Mail Steam Packet Co. brochure, 1906

Alice Rich Northrop was a botanist who toured Central America with members of her family. This brochure from one of her trips touts the ocean liner’s amenities: “These vessels are fitted with the Electric Light throughout, and all modern improvements, including luxurious saloons, Ladies’ Rooms, Music Saloons, Smoking Rooms, Refrigerating Chamber, &c. They thus offer unsurpassed facilities for Passengers traveling for pleasure and health.” Credit: Alice Rich Northrop Papers

Edna Rankin McKinnon passport, 1960-1965

McKinnon (1893-1978) was a birth control advocate who worked closely with Margaret Sanger. Between 1960 and 1966 McKinnon traveled throughout India, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, promoting birth control as a family planning and maternal health measure. She was instrumental in the formation of many family planning organizations and clinics throughout these areas. Credit: Edna Rankin McKinnon Papers

“Art Awheel in Italy”

Cornelia James Cannon recounts a trip to Europe she took with her four daughters and her sister-in-law. “The plan was to spend three months in Italy sketching for a part of each day. Bags of art material were to be our main baggage and a seven-passenger automobile with a top that could be thrown back at will was to be our conveyor.” This watercolor by Cannon’s daughter Wilma illustrates her mother’s typescript narrative. Credit: Cannon Family Papers

Boit travel diary, 1896-1898

Mary Anderson Boit (1877-1936) grew up in a wealthy Boston family. She was 19 years old when she set out on a European grand tour in 1896. She punctuated her text with illustrations such as this watercolor sketch. She describes rough seas and an uncomfortable journey, but after a few days touring Paris, she is overwhelmed with excitement, “I feel as though I never could write what I have seen there is so much that is wonderful in this city.” Credit: Cabot Family Papers