Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Art as cultural backdrop

Series highlights single works to frame eras and their social norms

Visiting an art museum usually means confronting a kaleidoscope of works. Paintings, objects, and installations can flash past like meteorites.

But a Harvard Art Museum lecture series this year invites art lovers to pause and focus on single works. During the “In-Sight” discussions, an art expert shows the audience how one example can open a window onto the culture, society, and history of an age. (The next lecture is March 3.)

The first lecture last fall centered on the left hand of a Japanese Buddha figure. The lacquered wood remnant was an entry point into understanding the sculpture, architecture, and religious traditions of 13th century Japan.

The second lecture looked at an Edward Burne-Jones watercolor. Set in context, it revealed the romantic temper of 19th century England, along with the materials, collecting habits, and reproduction techniques that informed art in that age.

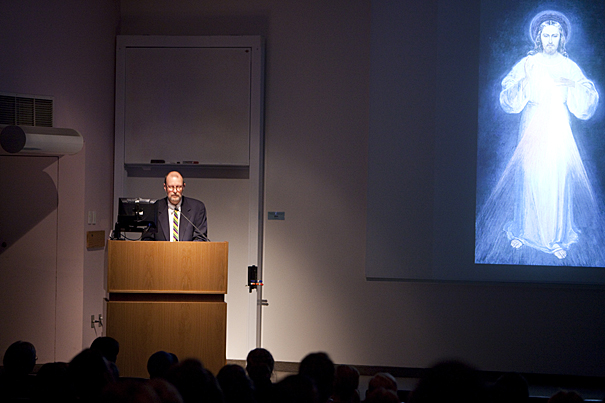

This semester, audiences at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum lecture hall have been guided so far through two disparate works from the 20th century: one an iconic religious image and the other a photograph that documented a social trend.

On Jan. 13, curator and historian Ivan Gaskell led the audience through a nuanced look at “Jesus Christ as the Divine Mercy,” a 1934 oil-on-canvas by Eugeniusz Kazimirowski, an obscure landscape painter and Polish veteran of World War I. That painting today is “among the most widely venerated images in contemporary Roman Catholicism,” and the object of cult-like adoration worldwide, said Gaskell, who is the Margaret S. Winthrop Curator at the Harvard Art Museum.

The shimmering, romanticized image — inspired by a nun’s vision — depicts a robed Jesus, right hand raised in blessing. Two rays, one red and one pale, emanate from his breast. Below, in Polish, is the legend: “Jesus, I trust in You.”

Though art and religion “have parted ways” in the modern West, Gaskell said, “Divine Mercy” is a fine case study on the power and durability that an image may command despite having limited aesthetic value.

In the Feb. 17 lecture, curator Michelle Lamunière used a gelatin silver print from around 1908 to explore how early photography could document social ills. Such pictures had many uses. They were pleas for change, and devices to underscore contrasting middle-class values such as thrift, order, and good hygiene.

“Twins When They Began to Take Modified Milk,” by an unidentified photographer, depicts an impoverished mother holding her scrawny babies. Behind her is a cramped, messy room. The picture was taken for the Starr Centre Association, a social reform society in Philadelphia. It was intended to advertise the benefits of pasteurized milk for infants.

“Twins” is one of about 4,500 photographs and 1,500 graphical illustrations on deposit at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, remnants of a Harvard Social Museum collection started in 1903. By 1907, it was housed in Emerson Hall as an exhibition arm of the new Department of Social Ethics, which in the 1930s was absorbed into Harvard’s sociology program.

The museum’s collection of realistic photographs was the brainchild of Francis Greenwood Peabody (1847-1936), Harvard’s Plummer Professor of Christian Morals from 1886 to 1912. Modeled after the Musée Social in Paris, it was designed to awaken “Harvard students ill-equipped for social challenges of the age,” said Lamunière, the John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Assistant Curator of Photography at the Harvard Art Museum.

But the Harvard Social Museum also displayed the “tension between sentimental appeal and science” that marked realistic photographs of that age, she said. Are “Twins” and photographs like it sentimental glimpses into impoverished parallel worlds? Or are they useful social documents, subject to rigorous scientific examination?

Both ideas appealed to Peabody, said Lamunière. Peabody kept the photographs in strict order by theme. They were documents, after all, intended to help “solve social problems, not to show social problems,” she said. But sentiment appealed to Peabody too, said Lamunière, since it was “critical to engaging students in issues larger than themselves.”

In their lectures, both Gaskell and Lamunière showed that single works of art, examined closely, can become entryways into the past and broader issues of art, politics, history, and culture.

For example, Lamunière used her lecture to survey social photography, starting with the stunning portraits of orphans taken for Thomas Barnardo (1845-1905), an Irish philanthropist who, starting in 1874, opened a series of homes for destitute children.

She acknowledged Jacob Riis (1849-1914), calling him “the father of reform photography,” who preferred sentiment to science. His traveling “magic lantern” shows shocked audiences with images of the poor and helped his reform efforts.

Gaskell showed how modern art slipped away from its old moorings in religious tradition. He identified J.-A.-D. Ingres and Eugène Delacroix as “the last prominent canonical Western artists to have produced devotional works for ecclesiastical use in the normal course of their careers.”

It was with Edouard Manet, a contemporary of Delacroix, that modern art was believed to begin, said Gaskell. At that point, a schism opened in the West between religion and art — or at least art as recognized by museums. Religious art soon met with skepticism or open hostility, attitudes that persist to this day, said Gaskell. (He quoted Picasso on the concept of religious art: “It is an absurdity.”)

But those who are not “art world artists,” said Gaskell, continued to fulfill the needs of religious authorities, creating traditional images readily understood by the faithful, for instance “Divine Mercy.”

The painting is so accessible, Gaskell said, that copies are sold in the gift shop of the U.S. National Shrine of the Divine Mercy in Stockbridge, Mass. Copies of derivative paintings also are available there.

Even a version of “Divine Mercy” downloaded from the Web is said to have the ostensible power to “grant graces to souls anywhere in the world,” said Gaskell, displaying the image on his laptop. That power has a modern ring, said Gaskell. It’s an image that does not require a physical manifestation, he explained, but like contemporary art “is properly conceptual.”

The next “In-Sight” lecture will take place on March 3 at 6:30 p.m. at the Sackler lecture hall, 485 Broadway. Amy Brauer, the Diane Heath Beever Associate Curator of Ancient Art at the Harvard Art Museum, will discuss “Mosaic of Two Figures Seated on a Couch,” A.D. c. 450-525.