In 2007, Harvard researchers Hugo Garcia (from left), Reina Flores, Vicky Karas, Barbara Fash, and Citlali Sanchez were in Yaxchilan, Mexico, bringing new technology to the archaeological site.

File Justin Ide/Harvard Staff Photographer

Beyond boundaries

As the pace of globalization quickens, Harvard embraces the world as its classroom

Shortly after being named Harvard’s vice provost for international affairs in 2006, Jorge Dominguez looked around and decided to declare victory.

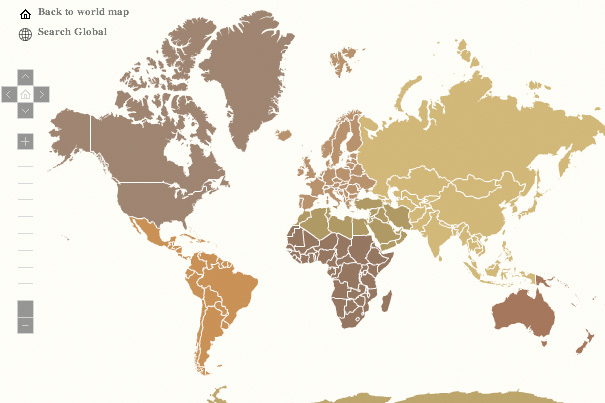

What Dominguez saw was a university that recruits the best scholars, regardless of nationality. He saw classes that teach 70 languages and topics ranging from Middle Eastern studies to world music to global fish diversity. He saw international students from more than 120 countries, who make up nearly 20 percent of the student body, and whose numbers grew 35 percent in the past decade.

Dominguez also saw a faculty that pursues the most important research questions, regardless of borders, and whose work takes them to the Earth’s far corners, from the Large Hadron Collider’s caverns in Switzerland to the Maya ruins in the hills of Honduras, to colonial-era archives in Kenya that recount historical atrocities.

He saw that there are 47,000 alumni abroad in nearly 190 countries, many holding pivotal positions. These include the sitting presidents of Liberia, Taiwan, Mexico, Mongolia, and Colombia, as well as the prime minister of Singapore and the secretary-general of the United Nations.

And Dominguez saw a university that encourages its undergraduates to venture abroad as a fundamental part of their education and as necessary preparation for leadership in a globalized world. As a result, in 2007-08 nearly 1,300 Harvard students studied or worked abroad, in 93 countries. By the time the 2009 Commencement neared, 58 percent of graduating seniors had traveled abroad while at Harvard.

“I did not have to make Harvard an international institution. My colleagues had already done the job,” Dominguez said. “We are vastly international. It is stunning and just simply amazing what the faculty, staff, and students do.”

But globalization speeds ever faster, so Harvard now must adapt to fresh challenges. In an intertwined world, issues involving business and economics, health and government, science and the humanities routinely cross borders. Technology has made the world smaller at the same time that its problems — from climate change to global pandemics —have become larger.

With those realities in mind, Harvard is ramping up efforts to help its students become global citizens of the 21st century, so they will be prepared to confront the knotty problems looming just beyond the horizon.

Harvard President Drew Faust has embraced Harvard’s international image in both practical and symbolic ways. Faust, whose appointment was celebrated around the world as an example of what women now can achieve, has traveled to China, Botswana, South Africa, Western Europe, and is now on a weeklong trip to Japan and China.

Her current visit bolstered Harvard’s long-standing Japanese relationships through meetings with government and university officials, and with some of Harvard’s Japanese graduates, whose international alumni club is the third largest behind those of the United Kingdom and Canada. Faust also visited a Japanese girls’ school, a familiar practice for her.

Faust then headed for Shanghai to speak at the official opening of the Harvard Center Shanghai, which has operated since 2008. The facility, the result of a partnership between the Harvard Business School and the Harvard China Fund, taps into Harvard’s and, more specifically, the Harvard Business School’s long relationships in China. It provides space for conferences and workshops in cooperation with Chinese universities, researchers, government, and public and private organizations.

Enriching student experiences

Harvard College began emphasizing undergraduate study abroad a decade ago, Dominguez said, when faculty and administrators realized that, with globalization on the march, international experience was becoming a critical part of a well-rounded education.

Andrew Gordon, now the Lee and Juliet Folger Fund Professor of History, studied in Japan as a Harvard undergraduate in the 1970s, taking a year off to do so. The experience fostered his interest in Japan, and helped prompt him to become a scholar in its modern history.

Gordon said students who head for Tokyo and Kyoto now tend to have one of two levels of experience. Some have studied the area and are familiar with its language, culture, and history. Others travel earlier in their academic careers, and their experiences may spark enthusiasm for further study.

Some students head off already committed to long-term study of Japan; others come back inspired to study more,” Gordon said.

Foreign experiences for students now come in all sorts of packages. A quick glance at the Harvard Summer School Web page shows programs in archaeology in Honduras, environmental studies in Venice, history in Jerusalem, language programs in nine countries, and science programs in eight. All of these Summer School programs started after 2000.

Harvard also has centers that focus on regional studies, such as the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies and the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, which create communities of scholarship focused on their target regions.

Lisbeth Tarlow, associate director of the Davis Center, said it annually supports 25 to 30 student research projects on the region. This year’s project applications include an ethnography of Muslim life in the Czech Republic and research on a Soviet sanitorium as a prism for environmental, medical, social, and cultural history. Tarlow said the center helps to foster area studies both at Harvard and on site through research funding, through foreign internships, by hosting scholars from abroad, and by providing logistical support for research in the field from a consultant whom the center retains in Moscow.

“All of this is really to foster a vibrant community of students, faculty, and scholars from a variety of disciplines to promote new thinking on the region,” Tarlow said.

Working abroad has always been an integral part of scientific fieldwork. Consequently, Harvard’s scientific faculty, scholars, and students conduct research from the Arctic to the South Pole. Students can participate independently or take classes where fieldwork is integrated into studies. For the past several years, biology professor Gonzalo Giribet has taken his students on a spring break specimen-collecting trip to the Caribbean. This year’s plans called for 14 students to spend the week diving on Panama’s reefs.

“In lab they see live animals, but they have no idea which group predominates in a reef,” Giribet said. While diving, “they see all the corals and sponges and understand where most of the biomass is.” They dive each day, bringing specimens to running-seawater tanks for analysis.

“We do a lot of collecting,” Giribet said. “I tell them they aren’t going on vacation in Panama. You’re going to work.”

Harvard students venture abroad in myriad ways. Members of the Harvard Glee Club performed in Canada earlier this month, while members of the women’s squash team traveled to India over winter break to play top Indian teams, and coach and tutor underprivileged children. Since January, students have worked on malnutrition in Uganda, on illiteracy in El Salvador, and on a clean-water project in the Dominican Republic.

Even as Harvard sends its students abroad, it also draws many international students to its classrooms, more than 4,000 of them in 2008-09. For instance, the Edward S. Mason Program at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) has long prepared talented individuals to address the world’s most compelling development challenges. This year, the program is sponsoring 73 midcareer professionals from 46 developing and newly industrialized nations in the School’s master’s of public administration program.

Paulina Gonzalez-Pose, the Mason Program’s director, said the outreach brings together a heterogeneous group of experienced professionals from the public and nonprofit sectors, and also welcomes those from the private sector who have made a serious commitment to public service. In its 52nd year, the program works to improve the analytical and leadership skills required to achieve major political, social, and economic change around the world.

Nontraditional classes, in the form of executive education programs, also draw midcareer professionals in areas ranging from business to government to law to health to journalism. The programs not only provide education in their fields, but they create valuable networks.

In 2007, a Russian submarine became entangled in fishing nets and was trapped on the ocean floor. While the world watched and tragedy loomed, a Russian admiral called a U.S. counterpart he had met in the U.S.-Russia Security Program, an HKS executive education session. That back-channel phone call jump-started a chain of events that resulted in U.S. and British assistance and the crew’s rescue.

Faculty coming here and working there

To Julio Frenk, the clearest sign of Harvard’s primacy as an international institution may be his own hiring. Frenk, dean of the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) since January 2009, was Mexico’s minister of health from 2000 to 2006 and is an authority on global health.

Frenk said HSPH has an international reputation, with a third of the School’s students coming from outside the United States. HSPH researchers work in 50 countries. In a recent survey, a third of the School’s faculty members said they spend 75 percent of their time working on research projects with a global dimension.

Frenk emphasizes that global health now includes domestic health, since medical problems now easily traverse national borders. In the age of AIDS, SARS, and H1N1, health inside a country can be influenced dramatically by what happens elsewhere.

Major research problems increasingly involve issues so large and broad that they require collaboration from scientists across disciplines and around the world, from the nature of human-caused climate change, to the best way to fight AIDS, to the creation of the world’s most powerful particle accelerator.

“The transition to a global outlook is becoming a unifying element of the work of faculty across the University,” said Frenk.

A portal for exploring Harvard’s worldwide activities »