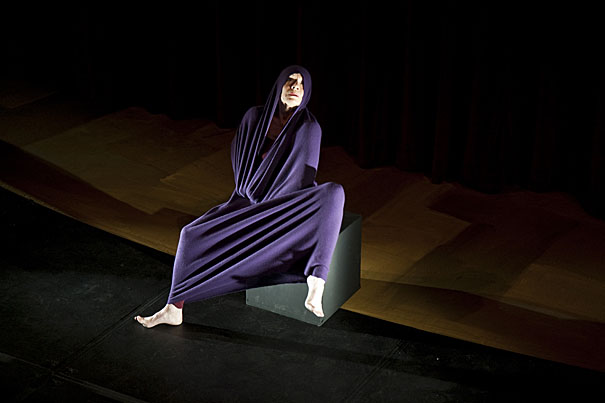

Dancer, former Radcliffe Fellow, and Martha Graham protege Christine Dakin presents the keynote performance/lecture at a two-day Radcliffe conference on gender and space.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Of men, women, and space

Radcliffe conference explores gender’s measurable dimensions

Space, the three-dimensional expanse in which the world rests, is everything that is not you.

On the other hand, space is everything that is you — everything under your skin and everything in and on your mind. Space is all.

Space is also something we share with other people (which can be difficult). Sometimes those other people represent the other gender (more difficult).

Welcome to the kind of tangled, terror-making, topical issues the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study likes to tackle in its annual conferences on gender, a staple since 2003. Previous events have looked at the intersections of gender and what seem like third-rail basics: war, race, reproduction, the law, food, and religion.

Now come gender and space. This year, Radcliffe tapped international scholars from various disciplines to puzzle over “Inside/Out: Exploring Gender in Life, Culture, and Art.”

Though there was a lot of talk (eight events over two days), there was also some quiet exploration — space flights, of a sort, as artists chimed in on the issue.

In a first for these Radcliffe conferences, said Dean Barbara J. Grosz in opening remarks April 15, an artist was explicitly included in every session.

Simon Leung — whose eclectic art has interpreted everything from surfing to Edgar Allan Poe — lent perspective to a panel on exteriors.

During a session on borders, Yael Bartana, an Israeli independent artist, showed vignettes from a film in progress. She is trying to capture a fantasy: Polish Jews, post-Holocaust, stream back to their native land by the millions.

On the first day, New York City dancer Christine Dakin, RI ’08, followed a panel on gender and space with a wordless contribution: Martha Graham’s 1930 “Lamentation,” in which writhing and suffering seem to transcend gender. “It was her art,” Dakin said to her audience afterward, perched alone on a stool on stage at the Agassiz Theater. “It wasn’t men and women.”

Still, she added, “Lamentation” was never performed by a man. Graham, whose views of gender ran to the conventional, meant it as a spatial picture of the feminine.

Both genders share a nongendered obligation in art, said Dakin, who once took the stage with dancer Rudolf Nureyev. There is “the necessity to move the air, to fill the space.”

On the second day, during a morning session on interior space in the Radcliffe Gymnasium, visual artist Janine Antoni, a tightrope walker and onetime MacArthur Fellow, moved the air with a wordless and kinetic “lecture.” In a test of intimacy within a public space, she walked through the audience on the backs of chairs, relying for balance on the outstretched hands of men and women.

“That was so happy,” said panel moderator Nicholas Watson, RI ’09, a professor of English at Harvard. “One barefoot person … transfixes a whole room.”

“Artists offer us another mode of thinking,” said Ewa Lajer-Burcharth during the conference’s first session. She is Radcliffe’s senior adviser in the humanities and Harvard’s William Dorr Boardman Professor of Fine Arts.

Issues of space and gender are not new. But the conference was intended to expand that discourse, she said. It brought up gender- and space-related issues of migration, non-Western perspectives on personal space, architecture, borders, sexual violence, and new digital communities that for better or for worse test gender’s meaning.

During the panel on interior space, Judith Donath, a Berkman Faculty Fellow at Harvard Law School, said the Internet has not lived up to the ideal that it would usher in a new age on post-gender space, in which men and women could roam freely without the burdens (or expectations) of gender identity.

For one, she said, the Internet is a place that people — suddenly bodyless — can lie about gender for excitement, comfort, or fun. But their words may betray them, said Donath. Even online, men remain more aggressive than women.

Space is a battleground in the gender wars, in part because of a cultural norm accepted for centuries: Men filled up space like Zeus, and women like a quiet wraith.

The feminine was to be either invisible, or, as University of Leeds social critic Griselda Pollock put it, “equated with what cannot be thought.” The feminine was not just meant to be invisible, but was a signal of absence, even of death.

The conference was informed by a notion of the shy female that persisted well into the 19th century, when American feminists awoke. They had to fight the cultural norms of retiring demeanor — near absence — that Emily Dickinson captured in an 1862 letter to a male friend. “I have a little shape,” she wrote. “It would not crowd your desk, nor make much racket as the mouse that dens your galleries.”

Women felt the weight of the same norms in the 20th century. In the keynote panel on April 15, “Conversation on Gender and Space,” Princeton University design professor Beatriz Colomina told the story of architect Eileen Gray (1878-1976) and her run-ins with architect and artist Le Corbusier (1887-1965).

In 1938, Le Corbusier was given the use of Gray’s remote seaside house near Nice, and proceeded to paint eight murals that Gray came to view as invasions of her personal domestic space, and an affront to her own design. “The mural for Le Corbusier,” said Colomina, “is a sort of weapon against architecture, a bomb.”

The act matched the violence of the later occupation of the house by German troops, said Colomina, and was rapelike, done with the arrogance of a conquerer. She said of Le Corbusier’s unwanted art: “Like all colonists, he does not think of it as an invasion, but as a gift.”

The effect of the murals, and their sexualized context, said Colomina, was heightened by the fact that Le Corbusier apparently painted them while naked. Her presentation included the only images of an undressed Le Corbusier known. (Historians take note: He is not someone easily seen naked.)

The controversy of gendered space reaches into the realm of science, too. On the same April 15 panel was Temple University psychology researcher Nora S. Newcombe, Ph.D. ’76. She was out to bust a few myths, among them the idea that males — by virtue of biology — have superior abilities to females.

Such differences in ability show up as early as age 4, in part because boys seem to gesture more. “Gestures take up space,” said Newcombe, and enable boys to develop a better sense of themselves as spatial actors. By middle school, the gap in spatial ability means that boys are more likely to stream into what she called “the stem occupations,” such as engineering and mathematics.

But spatial ability is plastic, not fixed, and can be improved by training, by restoring spatial equality between the genders. Such training “is not just part of a gender agenda,” said Newcombe. “It’s part of a social agenda.”

“Inside/Out” was also the beginning of a collaboration between Radcliffe and Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Dean Mohsen Mostafavi helped to moderate the first panel.

A Harvard professor of visual and environmental studies got the last word, with the impossible task of summarizing the conference at a final April 16 gathering.

Space is a place of transformation, said Giuliana Bruno, a place to test our senses of travel, dwelling, borders, privacy, and the act of living with others. Examining the notion of space, personal and private, is a way to test ourselves in the world, and our relation to it, like a tightrope artist walking on the backs of chairs.

“I would invite Janine to every conference we have,” said Bruno of Antoni, the visual artist. “After all, space is a fabric.”