(Boston, MA – April 13, 2010) Audience members listen as Mickey Chopra, Chief of Health and Associate Director of Programmes at UNICEF speaks about “Nutrition and Achieving the Millennium Development Goals” at the HSPH, Kresge Building. Staff Photo Kris Snibbe/Harvard News Office

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Reducing malnutrition

International goals for 2015 seem out of reach for many developing nations

The world is unlikely to reach the international goals set to reduce malnutrition or maternal and child mortality by 2015, authorities on global health and nutrition say. They believe that improving child nutrition is a key way to lessen all three.

Experts gathered at the Harvard School of Public Health Wednesday (April 14) for a symposium presented by the Harvard Nutrition and Global Health Program at the Harvard Initiative for Global Health. The daylong session drew authorities from around the world to discuss how to improve nutrition and how that would influence areas beyond public health, such as education and the economy.

The event was hosted by Wafaie Fawzi, professor of nutrition and epidemiology, and Christopher Duggan, associate professor of nutrition and of pediatrics.

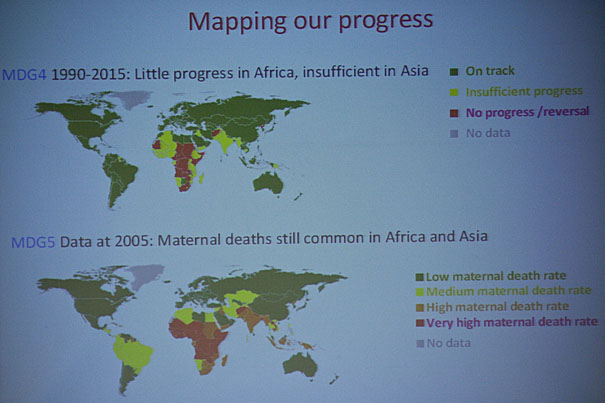

Nutrition Department chair Walter Willett introduced the session by outlining the eight Millennium Development Goals, adopted at a United Nations summit in 2000. The symposium focused on three of the eight goals: halving extreme malnutrition and poverty, and reducing child and maternal mortality. The other goals include guaranteeing universal primary education; gender equality; fighting AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; protecting the environment; and developing a global partnership for development.

Willett said each goal tackles an area of enormous challenge, but nutrition plays a role in achieving all of them. Though some nations, particularly those in East Asia and Latin America, have made progress toward achieving the goals, nations in Africa and South Asia have made little progress.

“It’s pretty clear we’re headed for a major shortfall on many of these goals,” Willett said.

In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the percent of the population that is hungry slipped from 1990-92 to 2004-06, falling from 32 to 28 percent. But that number rose again, to 29 percent in 2008. In 1990, more than half of the children in South Asia were underweight. That number fell a bit by 2007, but still stood at 48 percent.

Willett cautioned, however, that improving nutrition in the early years is not the end of the battle. Mexico, he said, successfully reduced its childhood mortality from undernutrition and infectious diseases, but has seen a rise in chronic diseases to the point where diabetes is the leading cause of death.

Mickey Chopra, chief of health for UNICEF, said the Millennium Development Goals were adopted not out of some concept of charity flowing from rich to poor countries, but rather out of a broader sense of social justice. Today, 195 million children under age 5 in the developing world have stunted growth. Not surprisingly, he said, countries with high levels of child malnutrition also have high levels of child mortality.

Chopra said that the first 1,000 days of life — roughly from conception through age 2 — are the most critical in avoiding malnutrition. Knowing that fact means interventions can be designed and prioritized to the best effect. Some countries such as Nepal and Malawi, though they have continued to experience economic and political hardships, still have been able to make progress toward the goals, through shifting priorities and targeted programs.

But while some countries have progressed without major infusions of cash, Chopra said that most will need to increase spending on health care to improve their situations. Fifty-seven countries have critical shortages of doctors, nurses, and midwives.

“It’s going to be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to achieve the goals without increasing money spent on health,” Chopra said.

Meera Shekar, lead health and nutrition specialist at the World Bank, said India is a particularly troublesome spot. It appears unlikely that India will achieve the malnutrition development goal by 2015. But even if it did, it would only reach the level where many African countries are today, she said. Malnutrition rates in South Asian countries, she said, are nearly double those in some African countries. Statistics show that many underweight children in South Asia were already small when born, meaning that interventions in the womb might be important.

It is generally accepted that poverty can lead to malnutrition, but malnutrition, in turn, can lead to poverty, Shekar said. Malnutrition leads to an average .7 grade loss in schooling and a seven-month delay in entering school. It eventually leads to a 10 percent or greater loss in lifetime earnings.