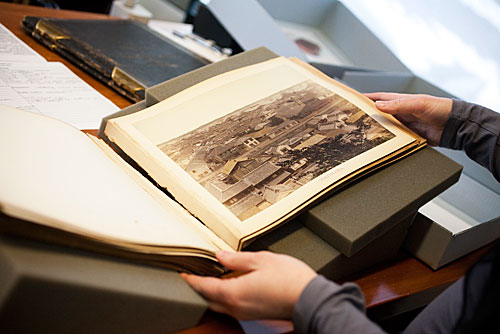

A group of staff members, including conservators, a curator, and a conservation scientist, from RussiaÃs State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg are guests of Harvard UniversityÃs Weissman Preservation Center through a ten-day residency with the CenterÃs renowned photograph conservation program. Tatiana Sayatina (from left), Natalia Laitar, Evgenia Glinka, and Natalia Avetyan examine volumes of photographs together. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Saving snapshots of history

Harvard helps Russian archivists learn to preserve photos

Four curators from the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, received lessons in photo conservation during a 10-day visit to Harvard, as part of a $3.4 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to establish a conservation program at the Hermitage.

The stakes are high. Russia’s signature museum, founded by Empress Catherine the Great in 1764, houses more than 470,000 aging and vulnerable photographs, some bound in fragile, ornate 19th century albums that belonged to the last czar.

From Jan. 20 to Feb. 1, the visitors — already skilled in organic materials, paper, paintings, and other conservation areas — worked with authorities at the Weissman Preservation Center, an arm of the Harvard Library devoted to assessing, treating, and preserving rare photos, paintings, paper artifacts, and other treasures.

During hands-on workshops, the Russian conservators studied photo album terminology and structure; digitization technology and work flows; survey methods; surface cleaning techniques; cataloging and housing; safe-handling strategies; and the ethical and practical considerations of removing photographs from albums and “disbanding” them.

“Albums have context” and should be preserved intact for their historical value, said Peter Kosewski, the Harvard Library’s director of publications and communications.

The visitors concentrated on assessing, treating, and preserving photo albums from the Hermitage collection.

“They had never seen things like book wedges before,” said Weissman Preservation Center Director Brenda Bernier, the Paul M. and Harriet L. Weissman Senior Photograph Conservator, who observed the visitors during their first hands-on workshop on albums. “Now they’re going to take their first solo flight.”

In the Weissman Center’s sunny fourth-floor conservation laboratory, the materials are so rare that elevator access requires a special code. While Bernier looked on, Catherine Badot-Costello, a book conservator at the Harvard Library, stood over a fragile album. It lay on a wedgelike foam cradle to relieve stress on the old binding.

She talked about issues like surface dust, leaf tearing, and planar distortion, the wavelike curl old pages can assume. “There are many problems with this structure,” said Badot-Costello.

That set off a bilingual conversation on the ethics of replacing or adding interleaving, the thin sheets of blank paper between album pages. Such changes can be “provocative,” said Harvard photo conservator and St. Petersburg native Elena Bulat, who provided translation when necessary.

The photographic holdings at the Hermitage represent “a very rare collection,” she said, including gift albums to the royal family from around the world, studio portraits, and even ethnographic views of 19th century Siberia, where the czar Nicholas II funded oil exploration.

Many photos were destroyed after the 1917 Russian Revolution, said Bulat. “Unfortunately, history in Russia worked that way.” But thousands of others were saved, guarded in remote corners of the Hermitage through several wars, she said. “Now the interest in this collection is incredible.”

The ethics of interleaving were just one of the discussions of conservation minutiae that drove the Russians’ visit. There were lessons on archival-level photo cleaning, starting with soft brushes and cotton, and then moving to white erasers and solvents, such as water-ethanol.

And there were lessons on paste recipes — concoctions of purified wheat starch that are reversible and that will not degrade fragile photographs and other objects. Such recipes are little known in Russia, said Bernier, so the visitors will go home with a recipe from Harvard.

The Russians were even treated to a close look at salt prints, the earliest kind of photographs, which date to 1839. Harvard has close to 3,000 of them, a high number. (University-wide, there are 8 million photographic images spread over about 50 repositories.)

Most discussions related to what experts call “treatment decisions.” The starting place is an assessment of each photograph or album, based on a detailed survey method developed at Harvard. The survey, designed to go directly to a computer program, was developed to assess the preservation needs in diverse, highly decentralized collections like those at both the Hermitage and Harvard.

The 10-day course on photo conservation was daunting and detailed. “Right now,” said visitor Natalia Avetyan, “my head is a hot pot.” She is curator of photographs in the Department of Russian History and Culture at the Hermitage.

The Hermitage already has 17 conservation laboratories, said Avetyan, and 126 staff conservators who are experts in painting, stained glass, archaeological artifacts, and other facets of art.

But the museum will soon have new storage systems and a laboratory devoted just to photographs, modeled on the Weissman system. And that model might one day spread Russia-wide, said Avetyan, simply because of the prestige of the Hermitage museum.

A department of photo conservation at the Hermitage could easily be considered just an administrative concern, an entity with a budget, staff, and space, said Boston photo conservator and consultant Paul Messier. “But to train the personnel … is quite another matter. This is where the Weissman Center really fits in. It’s a vital piece in the training curriculum for our Russian colleagues.”

Messier is co-director of the Mellon Foundation grant, which has a four-year clock that started ticking last March. The initiative to start up the Hermitage photo conservation program is led by the Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works.

Messier called the Weissman Center an ideal, comprehensive model for the Hermitage, since it’s a coordinated, multidisciplinary group of experts “all working together for a single mission.” Conservators, technicians, and catalogers join as a unit, often in support of digitization projects.

The Weissman template could be “scaled up” worldwide, said Messier, “to fundamentally establish photo conservation where it doesn’t exist, like Russia.”

Bernier said the Russians’ visit helped the University’s experts take a fresh look at photo conservation. “We’re very lucky that we have this very well thought out photo conservation program here at Harvard,” she said. “It’s gratifying to know it’s being looked at worldwide as a model.”