Mud, trash, and wrecked houses were swept a mile inland by the tsunami that struck Kesennuma and a swath of coastal Japan. Nearby, a Buddhist temple stood untouched. It was on land a mere foot higher in elevation.

Photos courtesy of N. Stuart Harris

At ground zero in coastal Japan

Harvard doctors raced to stricken region to help

In the days after a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami struck Japan on March 11, aid streamed in from the outside world — from robots and search dogs to fire crews and radiation experts. Still, the island nation has routinely declined offers of foreign medical aid, citing language barriers and its already robust disaster-relief infrastructure.

But there was one exception. Three Harvard emergency medicine physicians joined forces within a day of the disaster, and by March 14 were in northern Japan to help.

Their way overseas was eased by the Tokushukai Medical Corp., a major health-sector company. One of its executives is the father of Alisa Suzuki Han, a radiologist at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). Two members of the ad-hoc team were Japanese. The third, N. Stuart Harris, was American.

The team, said Harris, was the only one of American-trained doctors on the scene. With him were Takashi Shiga of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Kohei Hasegawa, a resident of the Harvard-affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency (MGH/BWH).

The Harvard doctors – thanks to colleagues at home covering their shifts – spent about a week in the field. They came back with tales of devastation, resilience, and hope. They also returned with one strong message: Pay attention to the real story.

The radiation crisis has captured recent headlines, they said, but the eyes of the world should be on the primary disaster zone. In coastal northern Japan, as many as 25,000 people have died, and many survivors are still suffering from shock and privation.

Shiga, who grew up near Tokyo, had visited the lush, forested area and its postcard-pretty islands as a tourist. But when he returned, he found a region seemingly “attacked by a bomb,” he said. “Entire small cities [are] gone.”

An attending physician at MGH, Shiga is also doing a fellowship at Harvard Medical School (HMS) on medical simulation. In that work, he uses specialty mannequins — which blink, have vital signs, and seem to breathe — to teach students about the emotions and uncertainties of real emergencies. When the fellowship is done in August, Shiga plans to return to help in northeastern Japan.

The 43-year-old Harris had spent two years in the same area (in Iwate Prefecture) right after college, teaching English in public schools. His primary base was in Iwaizumi, eight miles from the coast. But he also taught in the seaside fishing village of Tanohata, which was scoured into rubble.

The three Harvard doctors were posted to Kesennuma, a city ravaged by a rushing wall of water that Harris estimated reached 30 feet tall. The city heights, which are at about 2,000 feet, survived damage, but a broad peninsular plain at sea level was swept clean of houses and small factories. “Things were gone,” said Harris, who traversed the plain to deliver medical care. Left behind, he said, were 8-ton forklifts and concrete trucks, scattered like toys, and at least one deep-sea fishing vessel perched on a broken road.

But what the tsunami failed to remove was the quiet reserve, good humor, and resilience of the coastal Japanese.

Harris walked the plain one day with a 70-year-old man working for the Japanese Red Cross Society. They passed a patch of flattened concrete. “That was my house,” the man said, and walked on.

Harris treated an 84-year-old woman for chest pain. “I’m fine,” she kept saying. But she had lost a daughter and a grandchild to the incursive, penetrating sea.

Shiga treated a woman who when the tsunami struck ran toward higher ground with her family, chased by a wall of rushing water. “She turned around, and she was the only one” left, said Shiga.

“Why am I living?” she asked him. “Maybe I am living because I can pray for the rest of my family.”

The stoical reserve of his patients ran deep, said Shiga. “Unless I asked, they didn’t disclose.”

The Harvard team set up in a Kesennuma middle school, where 500 homeless residents slept on cots in the gymnasium, and a few hundred more bunked in empty classrooms. Most were “the very old and the very young,” said Harris, an indicator of the worrisome demographic issues that predated the tsunami. (Before the disaster, a third of Kesennuma’s 73,000 residents were over 65.)

The doctors and others established a primary care center and a makeshift emergency room in what was once the school nurse’s office. At night, they slept on the floor of an adjoining conference room — a motley scrum of local nurses, doctors, and public health workers.

There was no running water, no power, limited fuel for heating and cooking, and only a satellite phone for communication. “I have been a lot more comfortable sitting on a glacier at 14,000 feet,” said Harris, a veteran outdoorsman and chief of the Division of Wilderness Medicine at HMS.

They ate two meals daily, cobbled together in the school kitchen by volunteers. There was always rice, and usually miso soup with tofu or daikon radish.

Harris had brought warm clothes, water purification tabs, a sleeping bag, and a week’s worth of PowerBars. “The last thing you want to do,” he said of disaster zones, “is show up and make demands on limited local resources.”

Wilderness medicine has a lot to offer in disaster situations — a fact not fully appreciated yet in medical circles, said Harris. It’s the practice of “resource-limited medicine under austere conditions,” he said. “It was useful to have that background.”

Harris packed for the week like he was going on a frigid, high-altitude expedition to a mountainous region that he already knew was called “the Tibet of Japan.”

The landscape included both reminders of the disaster and reminders that life goes on. When Harris first flew into Tokyo, he quickly went to a staging point downtown (“where I felt my first earthquake,” he said), and soon was trying to get some sleep in the back of an ambulance, one of the only class of vehicles with free passage from the military on the earthquake-disrupted roads leading north. Snow fell steadily. The surrounding countryside was untouched by the coastal devastation.

Harris alighted in Sendai, the capital of Miyagi Prefecture. The dark, the snow, and the thought of the breached nuclear plants at Fukushima just to the south “cast a pall over things for the week,” said Harris, who developed his powers of observation at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he earned an M.F.A. before deciding to attend medical school. He compared devastated coastal Japan to scenes from Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic novel “The Road.”

Shiga and Harris discussed the low-key emergency medicine they practiced in Kesennuma. The crush injuries of a common earthquake were largely absent, or those that suffered them were already dead, and swept away. There were cuts, sprains, and soft-tissue injuries, but also the chronic illnesses that primary care doctors normally treat. Local doctors’ offices were gone, said Harris, so the ad-hoc medical team also dealt with blood pressure issues, diabetes, and kidney disease. Before long, 42 patients in need of dialysis were evacuated.

Another Boston-area specialist on hand was Japanese-born nurse practitioner Nahoko Harada, a pre-doctoral fellow and research assistant at Boston College. Her Facebook page now has a photo of the medical team in Japan, along with a button that reads “Pray for Japan.”

Shiga treated patients who were cold, sleepless, constipated, or who had minor injuries. In many ways, medical care wasn’t the main point, he said. “Mainly we were there to show them the world is interested in helping them, [to] bring hope to them. That was our main mission.”

Kesennuma was Shiga’s first brush with disaster medicine. He learned a powerful lesson right away. “Disaster relief is not only [about] trying to deal with trauma,” he said of responders. “We need to get there so people can maintain their hope.”

Mission Japan

Helping hand

A 70-year-old Kesennuma resident, volunteering with the Japanese Red Cross Society, hefts two medical kits while accompanying a Harvard physician on a medical round on the sea-level plain scoured by the tsunami. The man had just passed the remains of his own house.

Lifesavers

Nahoko Harada (from left), Kohei Hasegawa, Takashi Shiga, city resident (and kitchen organizer) Shota Miura, and N. Stuart Harris stand outside the Kesennuma middle school that housed an ad-hoc emergency clinic.

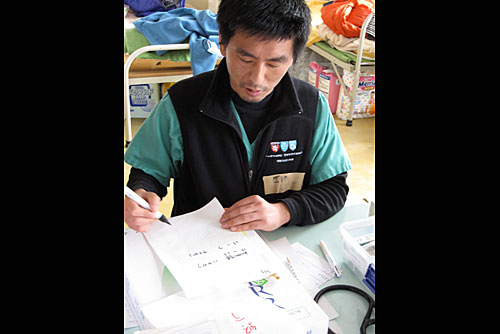

Making do

The gymnasium of a middle school in Kesennuma, where 500 residents made homeless by the tsunami bedded down every night. The school nurse’s office was the site of a temporary emergency room and clinic.

Bedside visit

In the Buddhist temple in Kesennuma — a temporary hospital after the disaster — an elderly man lies down, suffering without his medications. To the far left is Harvard-affiliated emergency physician Takashi Shiga. To the far right is Japanese-born nurse practitioner Nahoko Harada, a pre-doctoral fellow at Boston College.

Diving into the wreck

Mud, trash, and wrecked houses were swept a mile inland by the tsunami that struck Kesennuma and a swath of coastal Japan. Nearby, a Buddhist temple stood untouched. It was on land a mere foot higher in elevation.

Mayday

A wrecked fishing vessel, swept inland by the tsunami, perches on a roadway on a sea-level peninsula in Kesennuma. Before the disaster this fishing center was the shark fin capital of Japan.