Boston recluse Arthur Crew Inman’s 17 million-word diary, housed in Harvard’s Houghton Library, is the inspiration for an upcoming film project by Lorenzo DeStefano. “This film is not a celebration of some heroic character,” he says. “It’s more of a forensic investigation of the complex, surprising, and ultimately fascinating human organism known as Arthur Inman.”

Diary from a darkened room

Hollywood tackles the unbridled musings of recluse Arthur Inman

If screenwriter and director Lorenzo DeStefano has his way, one of America’s oddest literary stories will soon appear on the big screen, with all its Harvard connections intact.

“Hypergraphia,” a film project that has already signed Oscar nominee John Hurt for the lead role, tells the story of Boston recluse Arthur Crew Inman (1895-1963), whose 17 million-word diary is, one can safely assume, among the longest ever written. (By comparison, the diary of Samuel Pepys is a scanty 1.25 million words.)

The title is the formal name for the overwhelming urge to write — on walls, napkins, and skin if no other means of expression are available. It’s sometimes associated with temporal lobe epilepsy or bipolar disorder, though not in Inman’s case.

“He was a classic neurotic” and a strong hypochondriac, said neurologist Alice W. Flaherty ’85, M.D. ’94, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School who has chronicled her own bouts of hypergraphia. “This was a lonely guy. He shut himself away from the world, and he made himself happy by writing.”

Inman’s 44-year diary comes in at 155 volumes. It’s not great writing, she said, but a powerful illustration of the redemptive power of art. “A lot of people give up and turn into vegetables,” said Flaherty, who wrote “The Midnight Disease,” a 2004 nonfiction bestseller on the neural origins of creativity. But Inman earned her grudging admiration because he chose to be “a vital member of his tiny world,” she said, “his world of one person.”

Copies of the Inman diary were stashed for safekeeping in a Boston bank vault and even in a few salt mines. The original work now resides permanently in Harvard’s Houghton Library, along with photos, 100 hours of audio, and other artifacts.

It was a Harvard English professor, Daniel Aaron, who managed to edit the epic diary down to a modest 1,600 pages. “The Inman Diary: A Public and Private Confession” was published in two volumes by Harvard University Press in 1985.

“I read it straight through when it came out,” said DeStefano, then a film editor, theater director, and aspiring writer. He wrote a note to Aaron, and a year later — still fixated on the theatrical potential of the diary — caught a plane east to introduce himself.

DeStefano acquired the film and drama rights 10 years ago. Before scripting the film, he wrote two plays based on the diary, in 2001 and 2002, and signed off on a 2007 chamber opera composed by Thomas Oboe Lee.

But what was once a play “is very much a movie” now, he said, and will be an all-Massachusetts production. His partners include Brickyard Filmworks, a visual effects company in Boston, and producer Nicholas Paleologos, M.P.A. ’82, former director of the Massachusetts Film Office.

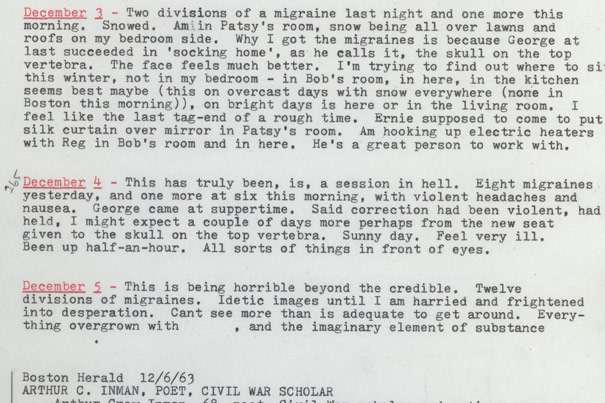

“Hypergraphia” will be a narrative film with documentary elements, including archival footage from the eras that Inman obsessively described day by day: Prohibition (his third entry rails against “this crazy act”), the Jazz Age, the Great Depression, World War II, and the cultural tumult that began with the Kennedy assassination. (Two weeks later, Inman shot and killed himself.)

The only son of a wealthy Atlanta cotton merchant, Inman first thought his self-published poetry would bring him fame. But his chief work soon became the diary. Virtually all of it was written in Garrison Hall, an apartment building in Boston’s South End where Inman — sensitive to light and noise and a hypochondriac — holed up in darkened rooms.

Waiting on him was a cast of cooks, maids, and handymen, along with his wife, Evelyn Yates Inman, who remained enigmatically loyal. Inman counted them among the 1,000 “characters” of the diary, the people whose stories brought the real world into his sheltered life.

Many were file clerks, waitresses, and schoolchildren — often girls from depressed circumstances — who were Inman’s “readers and talkers,” hired through classified ads for $1 an hour. While they sat with him in the dark, he pried away their secrets with charm and a genius for listening. Sadly, there was more. He called the girls — some as young as 12 — his “jade collection” and would often fondle them as they sat in his lap.

Meeting this Arthur Inman, even by way of his words, was unsettling, said Aaron — a mixture of “the grotesque and the comical. You’re simultaneously entertained and disgusted.”

DeStefano acknowledged Inman’s seedier side, along with his unhinged prejudices against blacks, Jews, and the poor. “This film is not a celebration of some heroic character,” he said. “It’s more of a forensic investigation of the complex, surprising, and ultimately fascinating human organism known as Arthur Inman.”

During the seven years it took to edit the diaries, Aaron wrote personal letters to Inman in his own journals, diatribes at the old recluse’s creepy lusts and the co-equal seductions of being sick. (Inman, said Flaherty, “had deep wishes to be alone — but cared for.”)

“He fancied himself a man of the world,” Aaron said. “But he wouldn’t have lasted a minute in the real world.”

But still there was “the very important work” of the diaries, he said, and “a richness and a denseness about a certain side of American life” in the common voices Inman reclaimed for history.

“I think it would make a wonderful movie,” said Aaron of Inman’s saga. “And it would make a wonderful soap opera.”