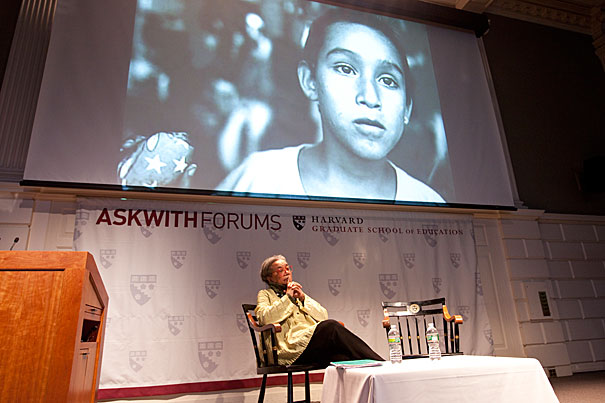

Longtime children’s advocate Marian Wright Edelman told a Harvard Graduate School of Education audience, “It’s time to build an irresistibly loud and adult voice for children.”

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

More roads to travel

Edelman says children, young minorities still badly served

Marian Wright Edelman has known dark days in her lifelong quest to help poor and minority children. In 1968, she went into Washington, D.C., schools to ask young African Americans to think of the future and stop rioting after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

“I am still haunted by the experience when one child looked me in the eye and said, ‘Lady, what future? I ain’t got nothing to lose.’ ”

Despite all the efforts of the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) that she founded in 1973, Edelman said there is even more reason today to be alarmed at the grim landscape facing many African-American and Latino children, with 80 percent reaching high school without reading proficiency.

“It’s movement time,” said Edelman, 72, a longtime children’s advocate, recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and a MacArthur “genius award” fellowship. “It’s time to build an irresistibly loud and adult voice for children.”

The national challenges are enormous: An average of more than one in five children lives in poverty; every 11 seconds a child drops out of school; every minute a baby is born with low birth weight; every three hours a child is killed by a firearm.

The prospects for black Americans today are worse than at any time since slavery, Edelman said, calling “incarceration the new American apartheid. Prison is the new Jim Crow and the new caste system.”

Many bright lights in education credit Edelman — with her no-nonsense style and steely commitment — for their entry into the field, said Dean Kathleen McCartney of the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) in introducing Edelman, who as a young Yale Law School graduate became the first African-American woman to pass the Mississippi bar.

“I often find myself reflecting on her wise words,” McCartney said: “It’s time for greatness, not for greed; it’s time for idealism, not ideology.” And it was Edelman who coined the admonition to “leave no child behind.”

In the final Askwith Forum address of the school year, Edelman recalled the long relationship of her organization with HGSE, where early “plotting” was done for the Children’s Defense Fund when she was director of the Center for Law and Education at Harvard. Just months ago, she said a team from CDF was huddling on campus with HGSE researchers on a consulting project. Relying on solid research, the CDF has helped to pass many major pieces of legislation to benefit disabled youngsters and poor children, to prevent teen pregnancy, and to combat gun violence.

Edelman said the solutions that CDF is hotly pursuing now are aimed at lifting minority students’ reading proficiency — not targeting test scores — and trying to intercept children at high-risk points of entry on the path to prison. She hopes that Freedom Schools, the summer and after-school programs that promote love of reading, will be established in every juvenile justice jurisdiction, with student teachers trained at black colleges and universities. And the Cradle to Prison Pipeline Campaign promotes conferences, such as one hosted in Boston by City Year, that focus on avoiding the warehousing of young blacks and Latinos in jail.

“This is a moment to act with courage and to combat the growing racial and class disparity,” she said.

Edelman lamented all the “silliness” of Washington politics, but predicted that despite lawsuits and conservative opposition, “We will hold onto the health care bill and the progress that has been so hard to get.”

She applauded the Obama administration’s work to protect funding for early childhood development and “investment at unprecedented levels in education.”

But she called on people to come together and let go of their own rigidity, saying, “We’ve got to break out of our silos of discipline.

“There’s not a moment and there’s not a child that we can waste.”