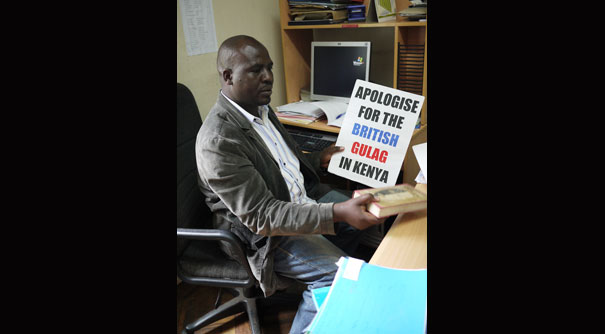

George Morara, a program officer with the Kenya Human Rights Commission, credits Harvard Professor Caroline Elkins’ scholarship and voluminous oral histories as the primary evidence for Mau Mau justice. “Without her seminal work,” he said, “this story wouldn’t have come to the fore.”

Corydon Ireland/Harvard Staff

Justice for Kenya’s Mau Mau

Historian helps make the case that aged veterans deserve justice

NAIROBI, Kenya — George Morara, a program officer with the Kenya Human Rights Commission, is compact and strong, like a boxer. But the fight on his hands now is to defend veterans of the Mau Mau nationalist movement in their sunset years.

It was partly his research, planning, and pleading that recently won the right to trial in a British court for these aging veterans of rebellion against colonial rule more than 50 years ago.

But a case against the British, who once ruled Kenya, would not have been possible without the work of Harvard historian Caroline Elkins, said Morara. He credits her scholarship and voluminous oral histories as the primary evidence for Mau Mau justice. “Without her seminal work,” he said, “this story wouldn’t have come to the fore.”

Mau Mau veterans, in search of an apology and financial relief, may get their day in court by 2013. But Morara fears that the longer the case drags on, the fewer Mau Mau will be alive to see a settlement.

Even in Kenya, he said, it took years for the Mau Mau to be recognized for their role, mostly during the 1950s, in liberating the country from British rule. A ban on recognizing Mau Mau veterans was lifted only in 2003, the same year that the Mau Mau War Veterans Association was founded. Before that, said Morara, “There was no (voice) for survivors.”

Until 2003, successive Kenyan governments had been “very ambivalent” about the Mau Mau, he said, and sometimes official feelings spilled over into rancor. Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s first president and a former political prisoner of the British, was once thought to have inspired the Mau Mau movement. But after independence he called the Mau Mau “a terrible disease.” His successor, Daniel arap Moi, aired similar feelings.

But once veterans had a voice, they moved quickly. In 2003, they appealed to the human rights commission for redress from the British, who oversaw a protectorate and then a colony in Kenya from 1895 until 1963. The Mau Mau uprising was essentially a war of liberation from British rule. It was also a time of widespread torture, rape, detention, and starvation in a “gulag” run by colonial authorities, according to Elkins, professor of history and African and African American Studies.

She is part of a Mau Mau oral history project, in collaboration with the Kenya Oral History Center. A related exhibit at Kenya’s National Museum is slated to open next year.

Oral histories also had a role in getting to trial. In 2006, the rights commission, in an effort led by Morara, interviewed 42 potential claimants. Five were chosen, including two women and three men. One, Susan Ciong’ombe Ngondi, has since died.

On a shelf in his office, Morara keeps tapes of all the interviews. “Every time we hear the veterans speak, they break down,” he said. “They (tell) absolutely painful, horrific stories.”

For the British government to continue to press its case for dismissal makes the issue “a war of attrition,” said Morara. “These veterans are old.” He estimated there are as many as 75,000 former Mau Mau fighters, scouts, and sympathizers still alive in Kenya. Most are 70 and older. Among the official claimants, the youngest is 75 and the oldest 84.

The five were chosen because they represented some of the abuses that occurred in the Mau Mau era. “It’s about torture,” said Morara of the case against the British. The two women had been raped. One man had been beaten and left for dead in a pile of corpses during the infamous 1959 Hola Massacre, in which 11 suspected Mau Mau were clubbed to death. The other two men had been castrated. Morara said, “They have no families.”

Even after the British court decision in July, Morara is puzzled by the attitude of British authorities, who continue to refine their chief arguments: that the alleged abuses took place too long ago, and that any responsibility was passed on to the new Kenya government in 1963. “They were not negotiating then, and they aren’t now,” said Morara of British officials, “which we find strange.”

In 2007 the rights commission made a request for an official apology to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. When this failed, the commission entered the “second phase” of its strategy in 2009, said Morara, by filing an appeal for trial with the Royal Courts of Justice.

At the same time, in an attempt to sidestep “legal technicalities,” he said, the commission appealed directly to Britain’s then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown, and in February 2010 met with his foreign secretary, David Miliband. It was then that Morara escorted the five aging Mau Mau veterans to No. 10 Downing St., the prime minister’s residence. They arrived elated, he said, with a “feeling there was movement toward closure.”

The group appeared at No. 10 Downing with several “options for justice,” said Morara. These included an appeal for an official apology, a welfare fund for surviving Mau Mau, community reparations such as schools or hospitals, and small monthly stipends for the veterans.

Miliband was sympathetic, said Morara, but was voted out of office later that year. Since then, he said, the regime of Prime Minister David Cameron has not been receptive.

It will take as long as 18 months before the issue gets to court, he said. Meanwhile, the rights commission has a strategy of its own: to insist that the statute-of-limitations issue be resolved concurrently with a full trial.

“For us, this is not just a cause,” said Morara of the Mau Mau case unfolding in Great Britain. “It’s a way to address transitional justice.” That is, it’s a way for Kenyans to address what he said were unresolved issues of land ownership, corruption, and tribal divisions traceable to the colonial era.

The first Mau Mau act of resistance occurred in 1947, and was a consequence of Kikuyu farmers being displaced by white settlers and their native allies. “This case,” said Morara, “gives us a chance to start a new national discourse.”

But the case is for the world too, he said, because it points to the universal fragility of basic rights. “Human beings, wherever they are, have a right to live in dignity,” said Morara.

Meanwhile, he and a staff of three at the rights commission are establishing a database of aging Mau Mau veterans, including the women who acted as scouts and who slipped into the forests around Mount Kenya to bring fighters food, weapons, and intelligence.

The database, built largely from information from veterans, includes five categories: those who were tortured and still bear physical evidence; those detained who no longer have evidence of physical torture; Mau Mau not detained or arrested; women and youth who acted as village scouts; and those in categories one through four who have died. In those cases, relatives and friends try to corroborate old stories, and provide identity papers and other documents and artifacts.

Jane Muthoni Mara, the surviving female claimant, was arrested long ago while taking food to forest fighters and acting as a scout, said Morara — an example of the women who did their part in the rebellion. “Without their support, the Mau Mau could not have gone for all those years.”

As for the years of pursuing a case for the Mau Mau survivors, Morara praised a supportive British public, whose general sympathy for the old fighters is a contrast to official positions. In the meantime, he said, “We’d be very glad if the American community joined in.”

Morara is also interested in what led up to the Mau Mau rebellion. Last month, he set out on a three-month swing through Kenya to gather oral histories about the colonial period up until 1952, when the rebellion came to a boil. “Mau Mau is not an incident,” said Morara. “It’s a process.”