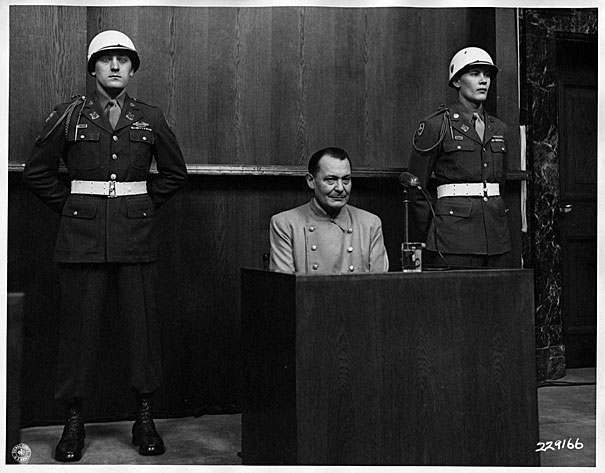

In addition to the digitized documents in the Nuremberg Trials Project, the Harvard Law School Library also has material relating to the international military tribunal, available through Harvard’s online catalog of visual images. In this 1946 photo, Hermann Goring, the commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, sits flanked by two military officers in the Nuremberg courtroom.

Image courtesy of Harvard Law School Library

Recording a horrific history

HLSL safeguards, digitizes document trove from Nuremberg Trials

The documents are chillingly frank. Faded with time, too fragile to touch, the photographs, papers, and reports tell of atrocities committed with a calculated, unspeakable precision.

The record represents a horror at once too painful to remember and impossible to forget. And historians, scholars, and educators worldwide agree the materials must be preserved.

The Harvard Law School Library (HLSL) is doing just that with its massive collection of materials relating to the trials of high-ranking Nazi military officials and political leaders during the international and the 12 U.S. military tribunals held in Nuremberg, Germany, from 1945 to 1949. In total, HLSL has about a million pages of materials related to the trials.

Through its Nuremberg Trials Project, the HLSL has cataloged and digitized more than 32,000 pages of prosecution and defense trial documents and evidence related specifically to the tribunals. The open-access collection includes trial transcripts, briefs, document books, photographs, and other papers.

Next to the National Archives, Harvard is believed to have the most complete record of the proceedings in the United States, because of the large number of Harvard Law School (HLS) lawyers involved in the trials.

Several factors contributed to the digitization effort, which took shape in the 1990s. As they aged, the original documents began to deteriorate. Despite careful preservation precautions, researchers eager to examine the materials were also unintentionally destroying them. Library officials ultimately restricted access to the collection to save it from further harm.

Documents were “disintegrating in people’s hands, and we realized we couldn’t make them available anymore,” said David Warrington, a librarian for special collections at HLS who worked closely with the archive for several years.

At the same time, HLS officials noticed a disturbing amount of Holocaust-denial rhetoric making waves in the public discourse. The heated debate, and a flood in one of the library’s sub-basements, where the documents were stored, added to the sense of urgency to process the collection for online use.

“We thought, ‘If we can’t preserve original documents and produce them, people will say this never happened,’ ” recalled Warrington.

The project’s first phase was completed in 2003 with the digitization of Case 1 of the military trials. Known as the Medical Case or the Doctors’ Trial, it involved 23 defendants, including Adolf Hitler’s personal physician and head of the Nazi euthanasia program, Karl Brandt. The group was accused of crimes against humanity because of devastating and deadly medical experiments.

Recently, the HLSL completed another stage of the project, digitizing all of the documents relating to Cases 2 and 4 of the military trials. Case 2, U.S.A. v. Erhard Milch, took place in 1946-1947. Milch was indicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The trial of Case 4, U.S.A. v. Pohl et al., occurred in 1947 and was brought against Oswald Pohl, chief of the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office, and 17 of his colleagues.

Initial funding for the project came through a grant from the Kenneth & Evelyn Lipper Foundation. Library officials hope to secure more funding to continue the project in the coming years.

Organizers say the collection is an important resource for those studying and researching current cases involving war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity, as well as a vital historical record.

Warrington, who tracked incoming questions about the collection for years, responded to requests from people who feared their relatives might have been on trial, and those who hoped to glean information about family members who were part of the Allied Forces or connected with the trials in some way. A significant number of inquiries came from college, high school, or middle school students working on projects or papers about Nuremberg.

“The reason why we keep and preserve these types of collections is for exactly the same reason we work at Harvard. We want to make the truth known over time,” said Warrington, “and we want scholars to think of Harvard when they want to do this kind of research.”

For Craig Smith, a digital projects assistant at HLSL who spent much of the past year digitizing the material, what stands out about the collection is the extent of the involvement of the German nation with the Nazi regime.

“The level of guilt extended to the entire organizational hierarchy of German society at the time.

“It was a very emotionally taxing project,” added Smith, “but a very important one.”