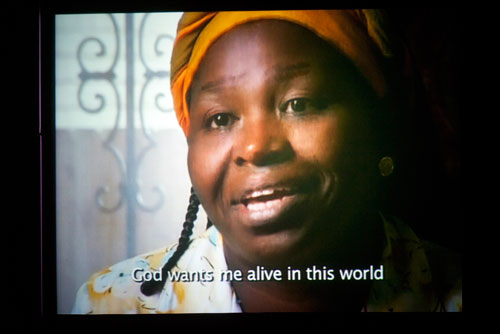

Women’s voices have long been absent from stories of war — and from the process of peacemaking. A group of women scholars and filmmakers gathered at the Kennedy School to explore those untold stories in conjunction with the new PBS series “Women, War, and Peace.” The panel included moderator Sahana Dharmapuri (from left), Elizabeth Medina, Helen Benedict, and Abby Disney.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Untold war stories

Women’s voices crucial in conflict and peacemaking, panelists say

When Abby Disney was writing her dissertation on war novels at Columbia, she noticed a curious pattern: Nearly all of them were about men, by men, and in most cases, for men.

But it wasn’t until she traveled to Liberia, in the wake of the country’s 14-year-long civil war, that she realized just how often women’s voices are stifled in the stories we tell about how wars are fought — and perhaps more important, in how peace is won.

Peaceful women protesters in Liberia had played a crucial role in bringing the conflict to an end and in unseating President Charles Taylor, but after their democratic victory they were “disappeared from the record,” she said.

“It really occurred to me that this is what it looks like as you’re erased from a story,” Disney told a rapt audience Tuesday night at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS).

Throughout history and across cultures, women’s voices have been largely absent from decision-making in wartime and from the process of negotiation that follows. Inspired by Disney’s new PBS series “Women, War, and Peace,” a group of women scholars and filmmakers gathered at the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum to explore those untold stories.

But honoring women’s voices isn’t just a symbolic gesture, the panelists stressed. If anything, women represent an untapped resource in peace building in many of the world’s 30 ongoing conflicts.

The practice of disappearing women from war — whether by silencing them through systematic violence, or by keeping them from the table during peace negotiations — seemed so pervasive to Disney that she took up the cause of unearthing little-known tales of women’s successes. (The first of five installments of “Women, War, and Peace,” for which she is executive producer, will air Oct. 11 at 10 p.m.)

Their stories ranged from the moving to comparatively mundane. One clip shown to the audience featured Liberian women, dressed in all white, gathering to protest mass killing and war. But another featured a group of Afghan women seated around a table and arguing about whether to support President Hamid Karzai’s promises to seat them at the country’s peace talks — political theater that could just as easily have taken place in the United States.

“This film shows the ways things actually are, not the way we’d like them to be,” said moderator Sahana Dharmapuri, a fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, which co-sponsored the event with the Institute of Politics, the HKS Women and Public Policy Program, the HKS National Security Fellows Program, and the HKS International Security Professional Interest Council.

What Disney hoped to convey was that “there are really effective, really bright women who are central” to peace building, a process that all too often fails.

Military and diplomatic leaders need to understand, Disney said, that women “function at the center of all the important social institutions. They understand what has to come first.” They can also be shrewd tactical advisers, she added: “They know where the weapons are. They know who’s corrupt and who’s not.”

Panelist Helen Benedict, novelist and author of “The Lonely Soldier: The Private War of Women Serving in Iraq,” relayed a story of just how complex the lives of women in war zones can appear to outsiders. When a group of American soldiers noticed that women in one Afghan village had to walk an hour each way to access a well, they decided to help them out and dug a well right in the town itself. The women were livid and destroyed it.

“That hour was the only time they could … talk without being watched,” Benedict said.

The “glamorizing” and “glorification” of war often found in men’s accounts of conflict “goes back to before we could even write,” and to the epics of Homer and Virgil, she said.

Women tell “a different kind of war story,” Benedict explained. Their perspectives on everything from the use of torture and rape by armed forces to concepts of honor and dishonor and the ethics of asymmetrical warfare can be quite different from those of men.

But if women have always played an unheralded role as civilians, they are only recently starting to affect how wars are fought and settled from the front lines. Elizabeth Medina, an Army civilian affairs officer and currently a National Security Fellow at HKS, offered a perspective from the other side of the conflict.

“You’re starting from scratch any time you’re newly on the ground,” Medina said. “We couldn’t possibly have the level of sophistication that it requires” to be completely sensitive to and aware of different cultures’ customs, she added. That’s why the military’s emphasis on learning from past experiences — an institutional value that is drilled into soldiers — is so important in developing the capacity to understand and include women’s perspectives on war.

For the past decade, the Army has deployed provincial reconstruction teams, Medina said, to go out into villages and empower local government officials. The hope is that such outreach will increase women’s representation in rebuilding Afghanistan and Iraq.

Disney said the American military has become quite progressive in its approach to war. Increasingly, she said, American soldiers view their role not merely as gun-wielding enforcers or combatants, but as community builders and mediators in war-torn areas.

“The military is so far ahead of our political culture on this issue,” she said. “They’re doing some of the best thinking about this in the world.”