Leslie Morris, the curator of modern books and manuscripts, helps oversee the John Updike Archive at Houghton Library. Once cataloged, his papers will be ready for researchers in the summer of 2012.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Treasure island

How Houghton Library saves and serves famed authors’ work

Almost three years ago, two archivists from Harvard’s Houghton Library appeared at author John Updike’s front door in Beverly. Barely three weeks later, America’s master stylist would die from lung cancer. “He knew it was time,” said Leslie Morris, Houghton’s curator of modern books and manuscripts. “He asked us to come.

Leaning on a walker, Updike chatted with Morris and her assistant while they packed cartons in his upstairs study. Into one box went the unfinished novel from his writing desk.

Updike had wanted to know that the outward signs of his literary ardor — decades of handwritten drafts, typescripts, galleys, and research files — would survive him. And he knew death was near. “Old age,” he had written in a short story, “arrived in increments of uncertainty.”

But there was no uncertainty about what should happen next at Houghton, the first building at an American university that was designed to house rare books and manuscripts. For decades, Houghton had been collecting the material now known as the John Updike Archive, which will be fully cataloged and ready for researchers by next summer.

In the end, the lives and thoughts of literary greats live on through their work and papers. Houghton and other Harvard libraries carefully tend the records left by dozens of prominent authors, providing pivotal research material for scholars.

The largest University repository is the Harvard University Archive, home to thousands of cubic feet of material, from doctoral dissertations and annual reports to books, maps, photographs, paintings, and artifacts. In addition, Baker Library at the Harvard Business School has about 1,400 collections of business manuscripts dating back to the 15th century. Radcliffe’s Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America has more than 2,500 manuscript collections. Harvard Law School’s historical holdings include 2,000 linear feet of legal manuscripts, some more than 800 years old.

But it is fair to say that Houghton is the mother ship for Harvard’s literary collections. Its 20th century holdings alone include the papers of T.S. Eliot, Thomas Wolfe, E.E. Cummings, Robert Lowell, John Ashbery, and Leon Trotsky. From the century before come world-class collections from Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and all of the creative James progeny: Alice, Henry, and William.

The point of such avid collection is scholarship. Houghton alone registers approximately 5,000 scholarly visits a year. In a hushed reading room, researchers — half of them Harvard faculty and students — pore over manuscripts, rare books, and letters that yield clues to literary creation.

But before that can happen, a busy and expert hive of specialists goes to work on the raw material that needs cataloging. Houghton typifies the intricate, difficult, time-consuming effort of processing and conserving rare documents, books, and other artifacts. That process begins the moment material arrives (sometimes haphazardly) in cartons, and continues until it is archived and housed in acid-free boxes.

“The refuse of my profession”

Updike ’54 began depositing papers at Houghton in 1966, just seven years after his first book was published. He later wrote of “the library’s meticulous, humidified care” for what he called “the refuse of my profession.”

That early “refuse” included James Thurber-like drawings, plays, proofs, and manuscripts, along with a paper written for a Harvard English class. It was about a former high school basketball player, and foreshadowed “Rabbit, Run,” the 1960 novel that catapulted Updike to fame. (He got an “A.”)

The author delivered a carton or more of material every year, said Morris. Other writers have a harder time parting with anything, and even stop by Houghton to visit their own papers. “Their archives,” she said, “are an extension of themselves.”

In their final visit to Updike’s house, Morris and an assistant retrieved the author’s Harvard Lampoon collection, some sketches he did in a postgraduate year at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art in Oxford, U.K., a box of recent correspondence, and all the multilanguage first editions of his books, which the meticulous Updike had neatly shelved in the order in which they appeared.

Very large literary collections destined for Houghton — Gore Vidal’s, for example — go straight to the Harvard Depository, a 25-year-old facility in Southborough with the capacity to shelve 3 million linear feet of material. One room there is often used to stack and store literary papers while experts begin the intake process they call “accessioning.”

But for the last of the Updike material, Morris and her assistant simply rented a Zipcar, drove to the author’s home, and spent the morning packing — but not before they had photographed the books as shelved.

Each collection starts with a doorway

Large or small, a literary collection first enters Houghton through a doorway across from Widener Library. In a copy room just inside, Morris and others make a rough estimate of what the collection includes. Boxes may then get moved a few feet to Morris’ offices. Lining a hallway there earlier this year, packed into archive-quality Paige boxes, was a trove of material from Andrei Sakharov, the Soviet dissident and physicist.

Through a door on the other side of the copy room is the office of Melanie Wisner, Houghton’s accessioning archivist, an expert on the first overview of a new archive.

“It’s order-making,” she said of the intake process, which includes writing a “box list,” entering it on a spreadsheet, and filing the collection in preliminary folders. Categories of order-making include correspondence, manuscripts, and materials related to research, biography, and photos. Wisner called the process an archive’s first “rough sort.” But Updike was so neat, she said, that “there was little to do.”

Accessioning means making initial judgments about what material is fragile and requires technical conservation. It also means being an author’s advocate, by identifying material that might be very private.

Privacy at Houghton is plentiful two floors below, in the sub-basement with its thousands of feet of shelving. Far back in the dark stacks — beyond the Theodore Roosevelt collection and the wide boxes of John James Audubon originals — shelves of Updike material await formal cataloging. Morris opens a box containing a complete set of the Harvard Lampoons from the year when Updike was editor (1953-54). Another box contains neat manuscript folders of his art reviews.

Nearby, up one ramp, is a large, well-lit space. Tables there are lined with open cartons and manila folders from the Updike archive. Jennifer Lyons, Houghton’s manuscript and visual resources cataloger, is looking at manuscript pages from “Rabbit at Rest,” the final novel of Updike’s famed Rabbit Angstrom tetrology. Lying nearby is what seems like an unlikely addition to literary scholarship: an empty, 99-cent bag of Keystone Snacks corn chips.

“He was a meticulous person in his research,” said Lyons, who started on the collection in July 2010. She pointed out other examples of the kind of studying Updike did to make his work shine with reality: reams of material about Toyota dealerships (the source of Rabbit’s prosperity), an outline of state license plates, and medical literature on heart disease (the cause of Rabbit’s death).

Updike was deeply involved in every detail of his final literary products, said Lyons. As a young writer in 1959, he even offered to design the cover for “The Poorhouse Fair,” his first novel. (The publisher graciously declined.)

The two-year task of cataloging the Updike material has been comparatively “fast and furious,” said Lyons. In the end, scholars will get a database of all the material related to his novels, poetry, essays, correspondence, and photographs. Archivists call this a “finding aid,” which lists folder-by-folder details. Such aids are not meant to be the granular details of everything, said Morris, but “a minimum level of description for a literary collection.” Discovery is up to researchers, she said, but synthesis is the responsibility of the archivists. They must be interested enough to do the work, but not fascinated enough to be stalled by every detail. Lyons said she might read more Updike one day, but for now “I go home and read something else.”

Twelve shelves of Updike’s books

Down another Houghton corridor is an example of the end point of an archivist’s exhaustive processing: 12 shelves holding a selection of the 1,357 books that Morris retrieved from Updike’s personal library. (Others, largely foreign-language and later editions, are stored at the depository.)

Some materials are housed in acid-free boxes, as part of what archivists call “end-processing,” the final step to assure that a literary artifact is protected, housed, bar-coded, and ready to hand over to a researcher. Other books have polypropylene jackets to protect fragile, first-edition covers. Still others are just coded and shelved, like the books Morris took off Updike’s writing desk. Those included his dictionary, two volumes on St. Paul (the subject of an unfinished book), and a book he had just reviewed, complete with annotations.

Elsewhere on the shelf are two of Updike’s books from his undergraduate years, one Melville and one Shakespeare. Houghton has both the teaching copy of “King Lear” used by celebrated Harvard English Professor Harry Levin (1912-1994) and Updike’s student copy from the same class. Both books have extensive marginalia. For a scholar, that could prove a perfect storm. Through such parallel artifacts, said Morris, “You can see the intersection of lives.”

On one shelf is Updike’s first-edition copy of “Rabbit, Run” (1960), an expurgated edition that he reworked for the British edition that allowed him to restore original passages about the euphoria and celebration of sex. Most of these additions and changes appear in Updike’s handwriting in the margins. Others are passages he typed and pasted onto relevant pages. Both provide a window onto the author’s creative process. “You can see what he’s adding back in,” said Morris.

Back upstairs, near the door where the material arrives, is the room where the process is completed. It’s the spacious realm of curatorial assistant Vicki Denby, Houghton’s resident expert on end-processing. Hers is a world of acid-free folders and stacked flip-top Hollinger boxes, in which most literary papers are finally “housed,” the term that archivists use when precious papers are finally snug and safe. Like houses, the boxes have addresses — bar codes these days — that allow staffers to find requests, and record who made them.

Looking up from one box, Denby said, “It’s a lot of work.”

Collected works Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Treasure trove

The lives and thoughts of literary greats live on through their papers, like in Houghton’s Library’s John Updike Archive. Updike began depositing in Houghton in 1966, just seven years after his first book was published.

John Updike

Leslie Morris, the curator of modern books and manuscripts, helps oversee the John Updike Archive. Once cataloged, his papers will be ready for researchers in the summer of 2012.

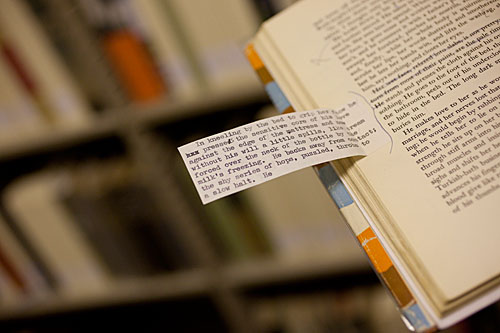

Revisionist history

Revisions, notes, and strikeouts are just many interests in this Updike volume.

A ‘neat’ man

Melanie Wisner, Houghton’s accessioning archivist, is an expert on the first overview of a new archive. Updike was so neat, said Wisner, “there was little to do.”

Literary criticism

An up-close view of one of Updike’s many papers.

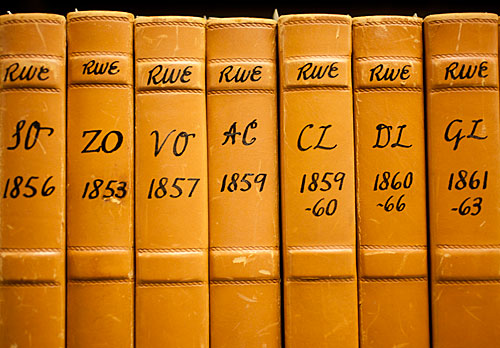

RWE

“He used his journals,” said Curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts Leslie Morris, “as his quarry.” That’s Ralph Waldo Emerson, of course.

Precious and fragile

Then there are the commonsensical restrictions on archival materials, “in many cases because of fragility,” said assistant curator Heather Cole. That concern includes items at Houghton that predate Christ.

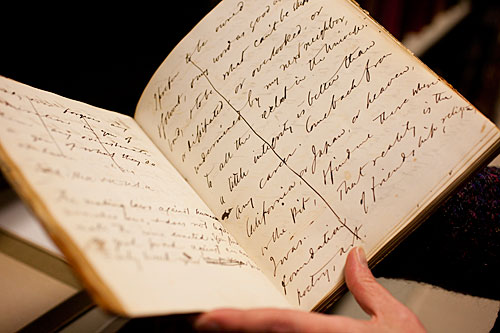

Journal entries

A handwritten journal entry by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Meticulous

“He was a meticulous person in his research,” said Jennifer Lyons, Houghton’s manuscript and visual resources cataloger, of John Updike. Lyons has reams of material devoted to Toyota dealerships (the source of Updike’s character Rabbit’s prosperity), state license plates, and heart disease.

‘A lot of work’

Curatorial assistant Vicki Denby works near stacks of acid-free folders and flip-top Hollinger boxes, where most literary papers are finally “housed” — a term archivists use to express the snug safety of precious papers. “It’s a lot of work,” she said.