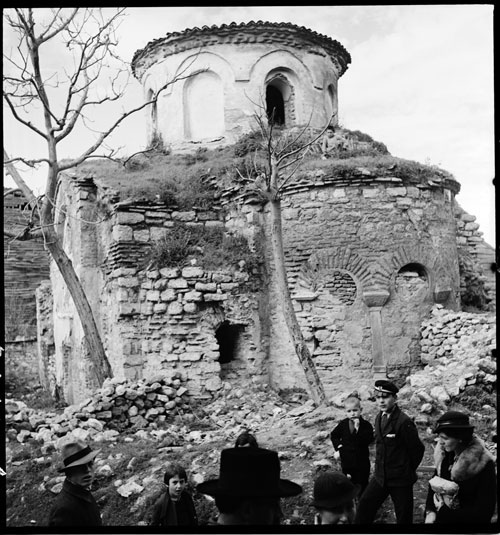

The Aqueduct of Valens was photographed by Nicholas V. Artamonoff in March 1936. Pictured is a slightly cropped version of the original image, which is part of the Nicholas V. Artamonoff Collection, presented by the Image Collections and Fieldwork Archive at the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, in Washington, D.C.

Photos from the Nicholas V. Artamonoff Collection

Snapshots of the past

Amateur photographer documented fading Byzantine ruins

Nicholas Artamonoff was a college administrator, a public works official, the son of a Russian general and military attaché, and an amateur photographer. A private man, he also became an unlikely champion at the center of a new online exhibit created by researchers at Dumbarton Oaks.

The Nicholas V. Artamonoff Collection, presented by the Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives (ICFA) at the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, in Washington, D.C., features more than 500 photos that Artamonoff took in Istanbul and at archaeological sites across western Turkey from 1935 through 1945.

The photos document sites and monuments, many of which have since fallen into disrepair or have disappeared entirely, which adds to the collection’s historical value.

To Günder Varinlioğlu, Byzantine assistant curator of ICFA, the body of work reveals a talented amateur who was intensely interested in photographing his surroundings. Although Artamonoff was not formally trained as an architect or art historian either, the images he captured through his lens are the work of a man who was dedicated to his craft and who had a profound understanding of historical monuments.

Varinlioğlu and intern Alyssa DesRochers worked last year to organize the collection, while researching both Artamonoff and his photography. Their efforts have resulted in a new online exhibit. The collection’s photos can be browsed or searched by title, location, or key word.

The images show 1930s Istanbul, a dynamic and romantic setting steeped in antiquity and well worth preserving for posterity. Jan Ziolkowski, director of Dumbarton Oaks, described Artamonoff as a “Casablanca figure,” and his Istanbul as a center of “multicultural, polyglot espionage types.” Even though Turkey is across the Mediterranean from Morocco, Ziolkowski said that the latter “has been in a similar position by being sometimes the edge of a tectonic plate between empires, and sometimes an imperial tectonic plate in its own right.”

Invoking tectonic plates calls to mind both the constant gradual change and periodic violent change that affect historic cities such as Istanbul. The relentless sun has faded aged frescoes, and the rhythmic waves have eroded sea walls, while successive iterations of urban renewal have claimed such important sites as the Aqueduct of Valens.

Varinlioğlu singled out Valens as an example of the urgency of archaeological preservation. The aqueduct, newly surrounded by a neighborhood in Artamonoff’s 1936 photograph, “represents the dynamism of a major center of population like Istanbul, as reflected by the fresh debris of recently demolished buildings. The urban fabric is like a living organism. Its transformation is inevitable, but it should not proceed in an uncontrolled manner at the expense of the cultural heritage.”

In later decades, the neighborhood surrounding the aqueduct made way for a highway. The landscape is sure to change further, but the researchers at Dumbarton Oaks hope that this photo collection encourages the preservation of visual and cultural memories, as well as the thoughtful restoration of monuments.

In the meantime, there is more work to do. Varinlioğlu and DesRochers continue to research Artamonoff’s life to enrich the collection’s context. They have identified additional Artamonoff works in the archives of the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. In addition, there are more images from the ICFA inventory that may be by Artamonoff. The exhibit organizers hope that viewers may help determine their authorship. They also hope that scholars, local residents, and others may recognize some of the many unidentified ruins and individuals in the photos.