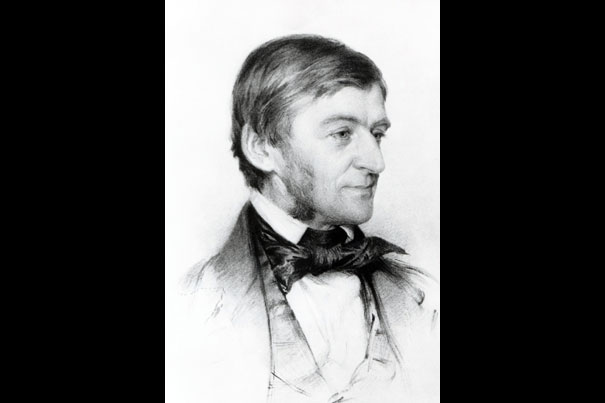

Ralph Waldo Emerson argued for the notion that the divine speaks within each of us. That concept has the root of a radically “democratic sentiment,” said David Lamberth, professor of philosophy and theology, one “antithetical to a tradition that took Jesus as the exemplar rather than one example among many.”

Images courtesy of Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School

When religion turned inward

After Emerson addressed the Divinity School, religion was forever changed

As Harvard celebrates its 375th anniversary, the Gazette is examining key moments and developments over the University’s broad and compelling history.

In a beautifully preserved chapel in Divinity Hall, an unassuming plaque honors a groundbreaking speech by one of Harvard’s best-known literary alumni.

The speech was delivered to a small gathering of mostly students, graduates and faculty on July 15, 1838, but it had a profound impact on the religious development of a burgeoning nation, the creation of a distinctly American cultural identity, and the future of Harvard.

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Divinity School Address” represented a turning point for Unitarianism, beginning its transformation from a liberal form of Christianity to a type of religious liberalism independent of specific historic traditions. The address also helped to establish Emerson as a major voice for the transcendentalist movement, involving an influential group of authors, philosophers, poets, and scholars who rejected the primacy of institutions in favor of the individual, intuitive thought, and the role of nature in helping man to understand the divine.

While Emerson had argued similar points in earlier speeches and essays, calling for relying on one’s own experiences and resources rather than on staid traditions in his works like “Nature” and “The American Scholar,” never before had he offered such a direct challenge to mainstream Christianity.

His words were so stunning and radical that he wasn’t invited back to campus for 30 years. Yet every July now, in commemoration of the speech, Divinity School officials give out free Popsicles, in part to celebrate “this refulgent summer,” the famous first words of Emerson’s landmark speech.

“I think that he was trying broadly to liberate the persuadable people in his audience — the graduating class in particular — from the sense that they should take their marching orders from church or doctrinal authority,” said Lawrence Buell, Powell M. Cabot Research Professor of American Literature, and author of “Emerson.”

A graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Divinity School (HDS), which was then known as the Harvard Theological School, Emerson followed his father’s vocation and took up a position as a Unitarian minister at Second Church in Boston in 1829. But, increasingly at odds with the church and its philosophy, he famously resigned his post in 1832, citing his inability to carry out the Holy Communion in good faith.

Six years later, speaking in Divinity Hall Chapel at the invitation of the graduating students, Emerson gave voice to many of his religious misgivings. He “railed against the emphasis placed on the personhood of Jesus as an authority figure,” said Buell. Emerson questioned the personhood of God versus man, and he argued for the value of experience.

Emerson argued for the notion that the divine speaks within each of us. That concept has the root of a radically “democratic sentiment,” said David Lamberth, professor of philosophy and theology, one “antithetical to a tradition that took Jesus as the exemplar rather than one example among many.”

“Emerson offers the idea not that we are like God, but rather that we are divine, insofar as we act out of this inner, essentially moral or ethical law which is within us.”

Emerson also took aim at the preaching practices of the day, calling for all sermons to include personal experience. He had a “trenchant critique” of relying on Scripture, doctrine, or tradition, said Lamberth, and argued that one has to “speak out of solely that which you have experienced yourself.”

“I once heard a preacher who sorely tempted me to say I would go to church no more,” Emerson wrote in his address. “If he had ever lived, and acted, we were none the wiser for it. The capital secret of his profession, namely, to convert life into truth, he had not learned.”

Much of Emerson’s genius, said Lamberth, lay in his inspiring prose and “his poetic ability to frame and advance ideas in such a textured and intellectually fecund fashion.”

“What he was saying was similar to what others said, but it was how he said it that made all the difference.”

The address also marked the beginning of a fundamental shift for Harvard. Though it would take years for the change to take hold, the speech was a catalyst for a Divinity School that would eventually educate not just ministers for New England, but men and women for the world.

The address advanced the notion that “a professional school does not need to train people only for a single career track,” said Dan McKanan, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Unitarian Universalist Association Senior Lecturer in Divinity.

Those who attended or were simply inspired by Emerson at that time “took the vision that he put forward in a lot of different directions,” said McKanan, who teaches the speech to first-year master’s of divinity candidates.

Emerson’s contemporaries responded. George Ripley, a Unitarian minister, became the leader of an experimental, utopian living community in Massachusetts. Theodore Parker, who graduated from the Theological School in 1836, created a new kind of church that was a “center for social reform activists in Boston.”

Echoing Emerson’s calls, current HDS graduates include “award-winning novelists, prominent journalists, social change activists, as well as ministers and professors,” said McKanan. Looking at that range of careers and interests, one can “see the address as a manifesto for a kind of professional education that is not limited to a single profession.”