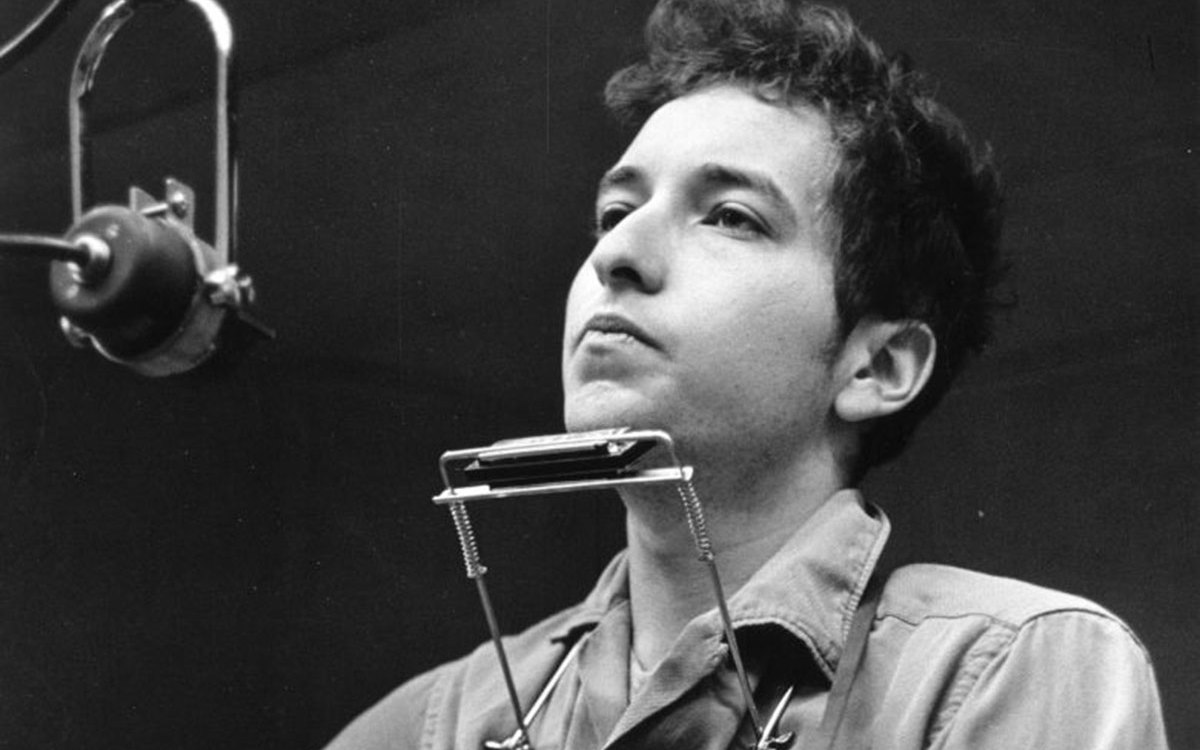

William Kentridge, who is delivering this year’s Norton Lectures, calls his series “Six Drawing Lessons.” The next lecture will be March 27 at Sanders Theatre.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Artist touts ‘primacy’ of images

In Norton Lectures, William Kentridge ponders truth and shadow

William Kentridge, the South African artist, animator, sculptor, drawing master, opera designer, and mime, can now add poet to his list of credits, since he is Harvard’s 2011-12 Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry.

That makes him the latest in a long list of great artists, writers, composers, and poets who since 1926 have delivered Harvard’s Norton Lectures, sponsored this year by the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard. (Among past lecturers — all charged with advancing the understanding of “poetry in the broadest sense” in at least six lectures — were T.S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Leonard Bernstein, and Umberto Eco.)

The 56-year-old Kentridge, who is gray-haired, funny, and still the supple mime, calls his lecture series “Six Drawing Lessons.” He roamed the stage at Sanders Theatre last Tuesday to deliver “In Praise of Shadows,” the inaugural talk. (The next, “A Brief History of Colonial Revolts,” is in Sanders at 4 p.m. on March 27.)

Kentridge received the invitation from Harvard 10 months ago, an honor that occasioned a conversation with his father, who asked: “Do you have anything to say?” In the end, the artist decided on a simple plan of attack for lecturing at Harvard: “I listed every thought I have ever had, then divided it by six.”

The “shadows” of the first lecture are those in “The Allegory of the Cave.” They flicker illusory and imprecise on a cave wall in Plato’s greatest work, “The Republic,” written around 360 B.C.E.

Plato invented those shadows as a puppet theater of reality for denizens of the cave, as stand-ins for humans, who have been shackled neck and foot since childhood so they can only see forward. The trope served as Plato’s view of how people apprehend the real world: as a poor copy of reality, as shadows on a wall.

That cave, and those deceiving shadows, said Kentridge, would be the centerpiece of the lecture series. “This is about the necessary movement from images to ideas,” he said, and also about the eventual “primacy of the image.”

Looming behind Kentridge onstage was a broad screen, and on it appeared first the artist’s heaven and hell: a blank notebook. Over the next hour, that notebook filled with a fluid supplementary video of scrawls, lines, blocks of type, bits of cinema, and phrases that acted like chapter headings. Kentridge’s own flickering hands moved everything about.

Early on, he showed a Plato-like fragment of “Shadow Procession,” his 1999 animation of the human condition. It is a foot parade of suffering, “a catalog of people on the move,” said Kentridge, inspired by street scenes from Johannesburg. Cutout puppets, hinged at the joints and in silhouette, limp, labor, and struggle to carry bits and bundles — even a city skyline. Plato’s philosopher, unshackled and free because he has seen the real light of knowledge, has a duty to return to the cave and free everyone, said Kentridge of that straggling procession. “If necessary, this has to be done by force.”

Perhaps the best way to do that is not through Plato’s vaunted reason or his intellectualizing of the surrounding world. Perhaps better is the force of art, Kentridge said, “a need to arrive at meaning” beyond spoken or written words. Kentridge imagined the logical and the rational as being states of mind that just hover over the real world and never really penetrate it.

But art penetrates. Humans “need to arrive at meaning,” said Kentridge, and what better way than to fall in with an artist “filling sheets of paper with signs and images.” In trying to capture reality in an image, he said, “the drawing becomes a meeting point” between image and reality. It becomes meaning, in all its glorious imprecision.

Kentridge called drawing “making a safe place for uncertainty,” and he hoped that his lectures could help do the same.

Plato’s would-be philosophers are unshackled and walk up toward the light of the real sun, Kentridge said, turning their backs on the shadows that flicker from the light of a fire. But then they are blinded, he explained, using the image of an eclipse of the sun. “All of Plato’s philosophical world has been simply blinded.”

The artist, however, is instead a master of looking at the light of the world in the oblique. To look at the eclipse, he puts a pinhole in a piece of paper and lets the blotted sun flow through that. Art intercedes. Instead of rationality’s blindness, he said, there is “the mute crescent of darkness eating into the sun” without harm.

Kentridge remembered the sun-scattering foliage at home in South Africa, where during an eclipse “there were as many moons as where the sunlight fell … 1,000 spots of light for every spot of darkness.”

So art exceeds the purely rational by multiplying versions of a single reality, like the eclipse — for a time when “every pinhole had its own sun,” he said. In this “promiscuity of projection” comes the promise that art makes to the world: Reality, instead of being a single shining thing, is a container for multitudes of meanings.

In that “universal archive” of light — as in art — there is also “everything that has happened on Earth … every event that has happened on Earth,” said Kentridge. We can see Pontius Pilate washing his hands, he said, and Martin Luther nailing his 95 Theses to a church door. But as in art, “every action, heroic and shameful, was there to be seen … Every foolishness is there.”

So art makes us naked and helpless in the face of light, or truth, but it also makes our own messages heard, said Kentridge. We are no longer that procession of shadows.

Plato was after the sun alone, the shining knowledge that stood at the peak of a hierarchy that descended from there to belief, illusion, and eventually delusion. That hierarchy opened the way to tragedy, said Kentridge, since knowledge always bring the right to power, and “the right to power is always the right to violence.” (More on that in the next lecture, he said.)

Back in the studio, projected on the big screen in Sanders, we see Plato as a typewriter, a machine of letters alone, said Kentridge. “What hope is there in it?”

The Norton Lectures are free and open to the public. Tickets are required and available beginning at noon on the day of each lecture at the Harvard Box Office or by phone (service charge applies to phone orders) at 617.496.2222. They also are available starting at 2 p.m. at Sanders Theatre. Limit two tickets per person.