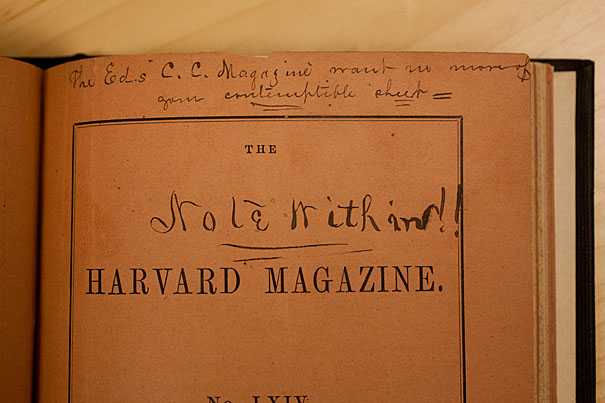

Harvard owns this May 1861 copy of the Harvard Magazine, which was returned by a miffed Southern reader — angry that this “contemptible sheet” would take the Union side in the Civil War. One of the magazine’s editors was 20-year-old Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Blue, gray, and Crimson

150 years later, the Civil War echoes across Harvard

Late on the afternoon of Sept. 4, 1861, the soldiers of the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment, fresh and eager for action after six weeks of training, boarded trains in Readville, Mass. They were headed south, to war.

The 20th was called “the Harvard regiment” because so many of its officers were educated at the College. Some had left Harvard as undergraduates, quitting school in April when the first rebel shells rained down on Fort Sumter. By 1865, the regiment’s nickname was “the Bloody 20th.” Of the nearly 3,000 Union regiments that saw action, the Harvard regiment had the fifth-highest number of casualties.

Harvard faculty, undergraduates, and graduates served in other regiments as well, and in every branch of the service. There were 246 dead among the 1,662 with Harvard ties who fought on both sides. In the Union ranks, 176 died. On the Confederate side, where 304 men with Harvard connections enlisted, 70 died, a mortality rate two and a half times higher than the Union side.

The Civil War, now in its sesquicentennial, helped to define the modern Harvard, just as it helped to create a modern America that embraced a stronger national government and a powerful capitalistic impulse. By the end of the 1860s, Harvard had a new young president, Charles W. Eliot, who led decades of sweeping reforms.

The war that tore apart the nation echoes into the present. Memorial Hall, a campus centerpiece whose tower overshadows the Yard, was built to honor the memory of the Union dead. They are named on tablets in the transept there, along with the battles in which they died.

Harvard’s current ties to the conflict begin at the top. President Drew Faust is a historian of the era whose 2008 book, “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War,” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award.

Another prominent Harvard historian, Louis Menand, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of English, wrote “The Metaphysical Club,” a study of the intellectual currents set in motion by the war. His book won a Pulitzer in 2002.

This semester, Harvard Professors John Stauffer and Amanda Claybaugh are teaching a course on slavery and the war. Stauffer is the author of eight books tied to the era. Claybaugh is working on a book about Reconstruction, the period from 1865 to 1877 that witnessed the beginning of a century of black slavery by another name.

But when those first trains of Harvard men and others headed south in 1861, no one could have envisioned the enormous bloodshed ahead, in which at least 640,000 soldiers and sailors would die in combat or from war-related disease. That was 2 percent of the U.S. population at the time. (In modern terms, said Faust, that would equate to 6 million Americans slain.) At Harvard College, the war’s death toll equaled two average class years.

The enormity of the war’s carnage came as a national shock, Faust wrote in “This Republic of Suffering.” “A war that was expected to be short-lived instead extended for four years and touched the life of nearly every American,” she wrote. “A military adventure undertaken as an occasion for heroics and glory turned into a costly struggle of suffering and loss.”

Off to war, from Harvard

Among the first enlistees in the 20th was the patrician Caspar Crowninshield ’60, the rugged lead oar of his College crew team and the sixth from his family to graduate from Harvard. His thoughts turned somber on the train ride south. “I could not help feeling sad as I looked around,” he wrote, reflecting on how “few might ever return.”

Union enlistments: 1,358

College, 608

Medical School, 387

Law School, 285

Lawrence Scientific, 54

Divinity, 23

Observatory, 1

Killed or died of wounds, 110

Died from disease, 63

Died from accidents, 3

Among the first to leave campus had been John Langdon Ward ’62, who departed five days after the attack on Fort Sumter. Within a month, already in the war zone, he wrote a letter back to an undergraduate magazine, describing his first picket duty: “T’was romantic — very.”

It was Crowninshield’s vision of the coming war, not Ward’s, that proved prescient. During the conflict, 1,696 men would pass through “the Bloody 20th.” Of the more than 700 soldiers on the trains that September day, just 44 would survive the Civil War.

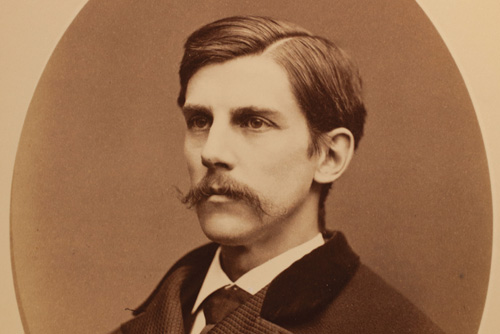

The southbound trains carried 25 baggage wagons, 120 horses, and a dozen deserters in chains. The regiment paused in New York City, where some officers — including 1st Lt. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. ’61, a future associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court — enjoyed a final patrician meal at Delmonico’s. Six weeks later, during the 20th’s first combat, Holmes would be flat on his back, spitting blood from a chest wound.

That minor engagement, at Ball’s Bluff, Va., on Oct. 20, was a rout for the outnumbered federal troops, a humiliating reprise of the Union’s defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run in July. For the 20th, the “butcher’s bill” — a term Holmes would later use in a letter home — came to 88 officers and men killed or wounded.

Confederate enlistments: 304

College, 94

Medical School, 2

Law School, 177

Lawrence Scientific, 31

Killed or died of wounds, 57

Died from disease, 12

Died from accidents, 1

Source: Harvard Alumni Bulletin, 1918

In her book, Faust rightly argues that the Civil War was the first modern conflict of attrition, with numbers so huge that authorities grappled for decades to get accurate counts. “Names might remain unknown,” she wrote, “but numbers need not be.” She described the conflict’s immense scale: 2.1 million Northerners under arms, and 880,000 Southerners — 75 percent of all Southern white men of military age.

Witnessing a theater of war so large and violence on such a scale changes people. “I started this thing as a boy,” Holmes wrote to his mother in 1864, after three years of service. “I am now a man.” In the same letter he acknowledged his exhaustion with the war. “I honestly think the duty of fighting has ceased for me,” a chastened Holmes wrote, “ceased because I have laboriously and with much suffering of mind and body earned the right …”

But in other ways the war retained its power for Holmes, who in 1902 joined the high court. All through Harvard Law School, past fame, and into old age, he kept his military moustaches. And all his life, Holmes, who lived until 1935, liked it when people called him “captain.”

In 1861, Holmes viewed the war as a moral action that affirmed his beliefs in racial equality and a unified country. By the end of his service, mentally spent and three times wounded, he had changed. “The war did more than make him lose those beliefs,” wrote Menand. “It made him lose his belief in beliefs.”

“For the generation that lived through it, the Civil War was a terrible and traumatic experience,” Menand wrote. “It tore a hole in their lives. To some of them, the war seemed not just a failure of democracy, but a failure of culture, a failure of ideas.”

Most scholars agree that the war made the United States modern, ingrained the notion of a strong central government, accelerated broad-based capitalism, and set in motion a cultural conflict over race, sovereignty, and states’ rights that still simmers today. Contemporary Civil War scholarship shows that even 150 years later, this transformative conflict still has the power to disrupt, puzzle, and even anger.

In some ways, the war is still being fought, chiefly on the battlefields of culture, said Stauffer, who directs Harvard’s American Civilization Ph.D. program. The course he is co-teaching with Claybaugh explores the temporal boundaries of the war that – in military terms – lasted from 1861 to 1865. In other terms, the war began perhaps as early as Nat Turner’s 1831 slave rebellion. After 1865, it went on at least until 1915, when the silent war film “Birth of a Nation” signaled how racial tensions still warped the embittered South.

Harvard ‘a touchstone’ of social forces

Stauffer and other scholars probe the war’s complexities. And in the years before 1861, Harvard itself was a prime example of those complexities, containing all of the boiling social forces that by 1861 made war inevitable. “It was a touchstone,” said Stauffer of antebellum Harvard.

Before the war Harvard, like the nation, was a place of factions and frictions.

Some undergraduates embraced a fierce New England abolitionism. One of them was the angelically handsome William Lowell Putnam, a Harvard Law School student who served with Holmes in the 20th. His grandfather had added to the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution the landmark sentence that began, “All men are born free and equal.” When Putnam died at Ball’s Bluff, his body was placed near a groggy Holmes in a field hospital. “Beautiful boy,” Holmes heard someone say nearby, and he knew it was Putnam.

Other undergraduates were hostile to the idea of abolition and the egalitarianism it implied. One was Henry Livermore Abbott ’60, a caustic elitist who nonetheless left Harvard Law School to join the 20th and defend the Union. He died at the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. Holmes praised the recklessly brave Abbott in a Memorial Day address in 1884, remembering the way he liked to swing his bared sword at the tip of a finger, “like a cane.”

In 1860-’61, still other Harvard students were patriotic, but remained sympathetic with a South that wanted to govern itself. Just before he enlisted, William Francis Bartlett ’62, who was known more for his skill at billiards than for his scholarship, wrote a school essay arguing the South’s case for independence. Yet he entered the war as a Union private, emerged as a brigadier general, and survived the conflict only at great personal cost.

In 1862, Bartlett was severely wounded in one knee, and three months later appeared — one-legged — at his graduation. Subsequent wounds to an arm, a foot, and his temple made him one of Harvard’s most battered veterans, “a wreck of wounds,” wrote historian Richard F. Miller, author of “Harvard’s Civil War,” a study of the 20th Massachusetts.

Still other Harvard students in that era were from the South, and quickly rallied to its cause. Eager to defend their homeland, they largely vacated the University in the winter of 1860-’61.

One of them was the improbably (but aptly) named States Rights Gist, who became a brigadier general in South Carolina. He had attended Harvard Law School from 1851 to ’52 and had helped in the bombardment of Fort Sumter. Gist was killed in action in 1864.

Another Harvard Confederate was John Frink Smith Van Bokkelen ’63, who early in 1861 joined a North Carolina regiment. He was mortally wounded at Chancellorsville in 1863. “While suffering from his wounds,” one writer later observed, “he spoke kindly of Harvard and his classmates.”

Perhaps Van Bokkelen knew that classmates were nearby. The 20th Massachusetts also fought at Chancellorsville, where Holmes received his third wound. During the same battle, Sumner Paine ’65, a freshly minted second lieutenant and just 17 years old, took command of the wounded Holmes’ company. Two months later, Paine was killed at Gettysburg at age 18, the youngest Harvard student to die in the war. Witnesses said his last words were, “Isn’t this glorious?”

The Harvard campus during the war

Paine’s last words were an echo of the wave of patriotism that swept the College at the outset of the war. “Intense excitement about the surrender of Fort Sumter,” wrote Harvard librarian John Langdon Sibley in a diary entry from April 15, 1861. That day, two members of the junior class left campus to join a Zouave regiment, cheered on by their peers and Harvard President Cornelius Conway Felton.

At the Divinity School, students raised money to buy a pistol for a Harvard volunteer. On April 29, amid rumors that a nearby arsenal would be attacked by “secessionists among the law students,” Sibley wrote, a force of armed students and faculty guarded it overnight. By May 1, he noted in his diary that the gymnasium, stripped of exercise equipment, “is beaten by military tramp” during student rifle drills.

Among Harvard’s graduates, the first to enlist after the attack on Fort Sumter was Henry Walker ’55. He reported to the Massachusetts State House — out of breath from running, his friends said. About the same time, six Harvard undergraduates signed up with the Union forces. Ten others left to serve with the Confederacy.

“We forebear to publish the names of the ten secessionists who have just left us,” wrote the editors of the April 1861 issue of Harvard Magazine, a student publication. A Southern sympathizer sent his copy of the next issue back, and inserted a scathing note. “All honors to the chivalric ‘ten’ who left you to do battle for their homes!,” it began. “As you are ‘eager for the fray,’ you had better visit now, and we will make you smell the powder and feel the steel of Southern gentlemen.”

In the offending issue its student editors had declared that “the voice of Harvard is for war!”

In 1861, there was no obligation for Harvard students to go to war. And there was no obligation for Harvard graduates to leave the comfort of their homes. But many did. Many gave up lives of privilege, including a graduate from the distant Class of 1825. Holmes, for one, was a direct descendant of the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He was also was the son of Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., who was both a literary light and a famous Harvard Medical School professor.

Harvard enlistees included a Who’s Who of famous New England names, from Bowditch, Cabot, Wigglesworth, Weld, and Whittier, to Dana, Hollis, Putnam, Sumner, and Winthrop. During the war, two Lowells died, along with two sons each from the Perkins, Abbott, Bachelor, Russell, and Revere families.

Yes, that Revere. Among the first staff officers in the 20th was Maj. Paul Joseph Revere ’52, grandson of the “midnight rider” of the American Revolution. A burly outdoorsman and champion of the poor, Revere was married, the father of two, and a successful businessman when he signed up in 1861. “I have weighed it all,” he said, “and there is something higher still.” He died on July 4, 1863, two days after being wounded at Gettysburg. His brother, Edward H.R. Revere ’47, had died earlier at Antietam, the only medical officer of the 20th to fall in combat.

Henry Ropes ’62, from a wealthy family, signed on with the 20th early in 1862, eight months shy of graduating. He was soon revered for being cool under fire, once remarking that bullets tearing through his clothes were simply “fishes nibbling.” Ropes died at Gettysburg.

Charles Russell Lowell, valedictorian of the Class of ’54, was another aristocrat turned warrior. He became a daring cavalry officer, whose clothes in one engagement were shot full of holes and his scabbard shattered by incoming fire. When Lowell died in combat in 1864, fellow cavalryman George Armstrong Custer wept, and Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan called him “the perfection of a man and a soldier.”

Then there was Robert Gould Shaw, perhaps the most widely known Harvard Union officer because he led the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, one of the first all-black federal units in the war. He was a wealthy abolitionist and man of letters who had left Harvard in 1859. Shaw died assaulting South Carolina’s Fort Wagner in 1863, and was buried in a common trench with his soldiers.

Holmes later said of Harvard’s contribution to the war, “She sent a few gentlemen into the field, who died there becomingly.”

In 1863, there were fewer than 2,700 living graduates of Harvard College. More than half of them enlisted.

Transformations, and sometimes not

The war had transformed Holmes, Bartlett, and other veterans, physically and otherwise. But at Harvard as the war played out, “College life went on much as usual,” wrote Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison in a 1936 study, “and with scarcely diminished attendance.”

On campus, the days were “interrupted and filled at times with great excitement caused by the Civil War,” remembered 1865 graduate Marshall S. Snow in a 1914 essay. After breakfast, he wrote, students would scan the bulletin boards for lists of casualties. Sometimes, the College chapel held military funerals. “Those were the days which made the most thoughtless students thoughtful,” wrote Snow, and “made them realize something of the cost of saving the Union.”

Far from the fighting, students enjoyed the intimacy of a very small campus. (In 1865 the faculty numbered just 18, including President Thomas Hill.) The students warmed their rooms with hard coal, drew water from the Harvard pump, and took meals at local boardinghouses. They watched as Grays Hall was built, as Massachusetts Hall got a new roof, and as a new sport came to Harvard: baseball.

Perhaps the most poignant sign of campus normalcy in those years was the presence of Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s son, who graduated in 1864. In the last few weeks of the war, he was a U.S. Army staff officer who, at the insistence of his mother, never got near the front. The young Lincoln’s one brush with trouble in college came in 1862. The faculty admonished him for smoking in Harvard Square.

Just after the war ended, Harvard veterans were invited to attend Commencement. The oft-wounded Bartlett was there, and Holmes too. Alongside them were more than 200 other returning veterans, many with empty sleeves and pant legs pinned up. They were all still young, one reporter wrote, but they looked old.

The invitation had come from the Class of ’65, which had lost just one of its number — Sumner Paine — in combat. During the ceremonies, Bartlett was invited to speak. He had drilled his men while standing on one leg. Deprived of mobility, he had routinely ridden into battle as the sole horseman. He had nearly died during eight months as a prisoner of war. Yet the strong-willed Bartlett, asked to speak, had trouble saying anything. He could only, and just barely, hold back his tears.