Restoring the building to its original state and treating the hall itself as a work of art are major goals of the revitalization effort, said museum officials, who hope to promote the continued use of the space as a teaching tool for researchers, scholars, and students, as well as a concert hall for its famous Flentrop organ.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The return of the murals

Adolphus Busch Hall re-creating much of its long-hidden splendor

On a recent morning, Daniel Ziblatt paused to gaze at the two bold frescoes that adorn the walls of Adolphus Busch Hall. The Harvard professor of government smiled, grateful he comes to work in a place filled with such stunning, albeit — in the case of the murals — “somewhat disturbing” creations.

“I am in awe every time I come through,” said Ziblatt.

He is one of the lucky few with an office in what was once the location of the Busch-Reisinger Museum and Harvard’s extensive collection of art from the German-speaking countries of Europe. The building’s main hall still contains a number of artistic treasures, including the two murals, created in the 1930s amid a political firestorm, and newly restored as part of a multiphase revitalization of the ornate space by the Harvard Art Museums.

Named for the philanthropist and brewing mogul Adolphus Busch, who helped to fund its construction, the building housed the Busch-Reisinger Museum from 1921 to 1991. Originally home to a collection of plaster casts of Germanic sculptural and architectural monuments, the museum’s emphasis expanded in 1930 when Charles L. Kuhn, fresh from his Ph.D. studies at Harvard, took over as curator. A strong proponent of the modern German art that was considered degenerate by the Nazis, he commissioned Harvard graduate Lewis Rubenstein, known for his social realism style, to create the murals for the building’s vaulted Rotunda Hall.

The evocative frescoes generated controversy long before they were completed in 1936. Rubenstein based the murals on ancient Germanic and Norse myths, but his inclusion of modern imagery left little doubt of their charged meaning. Fusing themes of social inequality, economic injustice, fascism, and war, he created two hauntingly provocative works.

Gods, equipped with modern flamethrowers and gas masks, repel an attack from giants in one panel. In another, a man with a thin but unmistakable mustache brandishes a whip while frightened workers cower beneath him.

For years, Rubenstein publicly denied the murals were political in nature, insisting they were merely artistic renderings of famous legends. But decades later, he bluntly said, “It was actually an attack on Hitler and the Nazis.”

The recent restoration confronted the recurring problem of efflorescence, the formation of white salt crystals on the frescoes’ surface. The building’s lack of climate controls and resulting fluctuations in relative humidity cause the chemical reaction, and have challenged conservators for generations with the reappearance of a hazy, white coating on the works.

Last fall, Louise Orsini, a former fellow at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, and her colleague, current fellow Gabriel Dunn, again tackled the delicate restoration process. Often perched high on intricate scaffolding, sometimes for hours at a time, they gently brushed away the powdery layer that had long obscured certain sections of the murals almost entirely from view.

To cover “glaring white” sections where the painted plaster had come loose, they applied a special conservation-grade adhesive and reattached large intact flakes. In other areas, they filled in missing or faded color with fresh matching paint.

Richer hues and revived images are the vivid rewards of their diligent work. In one of the lower panels, a background scene, previously invisible, now appears perfectly clear. “A lot of depth and perspective was completely flattened before,” said Orsini, of the lower panel’s missing body of water and horizon line. “That was completely illegible.”

During the next phase of the restoration project, workers will replace the Plexiglas panels that cover the murals’ lower sections, adding newer, nonglare models. One covering also will be fitted with an environmental conditioning system to help control humidity and to mitigate the efflorescence. Conservators will monitor the section closely over the next several years to determine if the new system helps alleviate the white film.

Workers have repainted walls, repaired leaks, and replaced railings and an 800-pound faulty radiator. In recent weeks, a master stonemason has been carefully removing traces of signage once affixed to its limestone walls and Art Museums staff have updated signage and restored several of the plaster casts.

Soon, visitors to the building may also get a peek at other objects that have been hidden from view.

Tucked behind the choir screen, a plaster cast replica of the 13th-century original from Germany’s Naumburg Cathedral, are many more plaster casts from the Harvard Art Museums’ vast collections. Officials hope to replace current wooden doors in the screen with Plexiglas to create a visible storage area, a common practice for museums with more art to display than available gallery space.

“It’s a wonderful way to make visible that moment in the Busch-Reisinger Museum’s collecting history and the historical role of plaster casts, especially for a teaching museum,” said Lynette Roth, Daimler-Benz Associate Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, who helped initiate the project.

Restoring the building to its original state and treating the hall itself as a work of art are major goals of the revitalization effort, said museum officials, who hope to promote the continued use of the space as a teaching tool for researchers, scholars, and students, as well as a concert hall for its famous Flentrop organ.

“Our aim is to showcase the objects still housed here and to highlight the architecture of the building,” said Roth, “to treat it with the same kind of care that we would treat works in our collection.”

Restoring Busch Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Controversy

The works of muralist Lewis W. Rubenstein sit in Adolphus Busch Hall. The murals were created in the 1930s amid a political firestorm, and newly restored as part of a multiphase revitalization of the ornate space by the Harvard Art Museums.

Busch league

Michael Eigen, assistant facilities manager at the Harvard Art Museums, takes in Busch Hall. Named for the philanthropist and brewing mogul Adolphus Busch, who helped to fund its construction, the building housed the Busch-Reisinger Museum from 1921 to 1991.

Making history

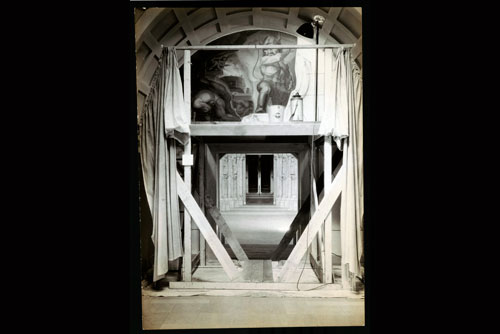

A snapshot by an unknown photographer, c. 1935-36, shows a view of Rubenstein’s fresco in progress on the north wall of Busch Hall.

Entryways

A close view of the plaster cast of the Hildesheim Cathedral bronze doors.

Plaster cast

A view of the plaster cast of the Freiberg Golden Portal and the sandstone sculpture “Spring” (c. 1760-1765), by the workshop of Johann Joachim Günther.

Gods and giants

A detail of one panel of the restored murals by Lewis W. Rubenstein, “Scene from the Ragnarök Legend, Battle Between the Gods and Giants,” c. 1935-36.

9.DDC111924_500

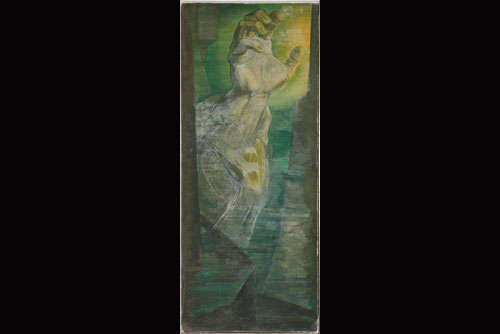

Photographed before treatment is Rubenstein’s “Scene from the Nibelung Legend, Alberich’s Hand,” c. 1935-36. Photo courtesy of Digital Imaging and Visual Resources, Harvard Art Museums.

Otherworldly

This view of Busch Hall shows its magisterial, almost otherworldly beauty, featuring plaster casts of the Naumburg Cathedral west choir screen and the Collegiate Church of Wechselburg triumphal cross.