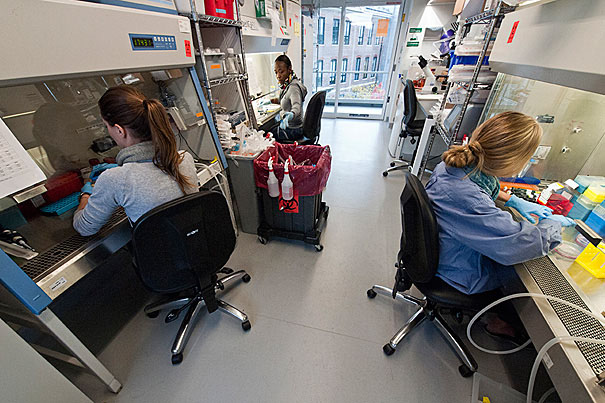

A two-year demolition and reconstruction project to accommodate the Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology Department has transformed the Sherman Fairchild Building into one of the University’s greenest and most efficient laboratory spaces.

B. D. Colen/Harvard Staff

The greenest lab, up and running

Renovation of Sherman Fairchild Building marks transformation

The renovation of Harvard’s Sherman Fairchild Building may have seemed inconsequential to the casual observer because the exterior barely changed. However, as a result of a two-year demolition and reconstruction project to accommodate the Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology Department (SCRB), the interior has been transformed into one of the University’s greenest and most efficient laboratory spaces.

The project, the first to utilize Harvard’s 2009 Green Building Standards to guide project development, recently received the Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ (FAS) first Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Commercial Interiors Platinum certification — the highest rating possible — from the U.S. Green Building Council. The certification follows the registration of Harvard’s 100th LEED green building project, which is the build-out of the laboratory for incoming Professor Daniel Nocera.

“Laboratories are the most energy-intensive spaces on campus. As part of our goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 30 percent by 2016, Harvard has focused on creating greener, healthier labs through a combination of energy-efficient renovations, resource conservation, and partnering with researchers to promote energy-saving practices in their labs,” said Jeremy Bloxham, Mallinckrodt Professor of Geophysics and dean of science in FAS.

From the beginning of the design process, the project team was committed to meeting clearly defined sustainability goals. Harvard’s Life Cycle Costing Calculator was used to vet cost-effective energy systems that will reduce the building’s ongoing environmental footprint and operational costs. The team also worked extensively with researchers and building operations staff to ensure that the finished space would maximize energy efficiency and resource conservation while meeting their cutting-edge research needs.

“The SCRB faculty and administrators responded enthusiastically to the challenge of designing and operating green laboratories. Together with the FAS Project Team, we created labs that really deliver on the promise of energy-saving design and technology without sacrificing the scientific research to be conducted in the buildings,” said SCRB Executive Director Kathryn Link.

The new energy efficiency measures include an internal heat shift chiller to capture heat from high-load zones and redistribute it to other parts of the building, occupancy sensors on fume hoods so they close automatically when not in use, heat recovery from zebrafish tank exhaust air, and windows to provide natural ventilation in nonlab spaces. Designers also targeted electricity use by reducing overhead lighting and including LED task lighting at laboratory benches. By reducing air flow change rates during unoccupied periods with the use of occupancy sensors, the building is estimated to consume 11 percent less electricity and 51 percent less steam annually.

“The new space dramatically reduces the amount of energy used per occupant, thanks to state-of-the-art energy-reduction technologies, such as the internal heat shift chiller and heat recovery system,” said Michael Lichten, associate dean of physical resources and planning at FAS. “The healthy, productive and creative laboratory workplaces also maximize use of daylight and fresh air, while optimizing an indoor environment that responds to a diverse range of research and office demands.”

Extensive water conservation measures include the use of re-captured “gray” water for toilet flushing, and low-flow fixtures that are projected to reduce water use 42 percent below the maximum required by building codes. The recycled water will appear blue to identify it as nonpotable.

“Now that Bauer Laboratories and the Sherman Fairchild Building are fully occupied and buzzing with research, the whole SCRB community of scientists, staff, and students has gone green by hosting the first lab-oriented environmental competition at FAS, piloting a very successful plastics-to-glass lab supplies program, and championing the use of tap over bottled or delivered drinking water. We plan to continue these efforts moving forward and cultivate a culture of sustainability,” continued Link.

Researchers have also participated in the FAS Freezer Maintenance Program to improve the longevity of the -20 and -80 degree freezers, to achieve energy savings, to improve sample security, and to reduce the risk of freezer failure.

“Because laboratory research is so resource-intensive, we as researchers have a special obligation to take whatever actions we can to reduce the environmental impact of our work. A major challenge for us as a community is to find ways to do this without compromising the scope and pace of our research,” said Dena Cohen, a research specialist in the Melton Lab. “We have focused on ways to reduce the huge amount of plastic that we put into the waste stream every day. By recycling as much as we can, and by substituting reusable glass products for plastic whenever possible, I think we have succeeded in dramatically reducing the amount of waste we produce, without impeding our research.”

The Harvard green building and sustainability project team included the FAS Office of Physical Resources and Planning, the FAS Green Program, the Harvard Green Building Services, and the Harvard Office for Sustainability. A LEED case study of the Sherman Fairchild project is posted on the Harvard Green Building Resource website.