A detail from an 1817 map, engraved by D. Haines, showing the “seat of war” — the vast North American territory in dispute during the War of 1812. (Courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection)

Photos of archival images by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard in the War of 1812

With action elsewhere, College’s losses included a sloop, slate, books, and firewood

On Feb. 13, 1815, a sudden clangor of bells erupted in Cambridge, so “loud & incessant,” wrote Harvard College sophomore Thomas McCulloch, that everyone in his mathematics recitation gathered at the windows to stare outside. In a letter to a friend the next day, he wondered: Was there a “calamitous conflagration” close by? But then the boom of cannon joined the peal of bells, and McCulloch realized that this was no fire, but rather a celebration. The War of 1812 was over.

The conflict actually had ended three months before, but news traveled slowly back then. Now, the Harvard University Archives is right on time with an exhibit that just opened, commemorating the 200th anniversary of this little-remembered tussle between nations.

“Harvard and the War of 1812: Slate, Sloops, and Celebrations,” on view through Dec. 14 in the lobby of Pusey Library, shows that the war touched the College only lightly. “Harvard men played little part in the War of 1812,” wrote historian Samuel Eliot Morison in a 1936 history. But the end of the war, in which about 20,000 British and American soldiers and sailors died, was fervently celebrated in New England.

The conflict, after all, had reduced regional profits from the cross-Atlantic trade with Britain. At Harvard, celebrations in March of 1815 included the flags of 60 nations fluttering atop College buildings, a sumptuous banquet, and written sentiments illuminated in building windows by hundreds of candles. The illumination at Massachusetts Hall read Arma cedant togae (“Let force yield to statesmanship”).

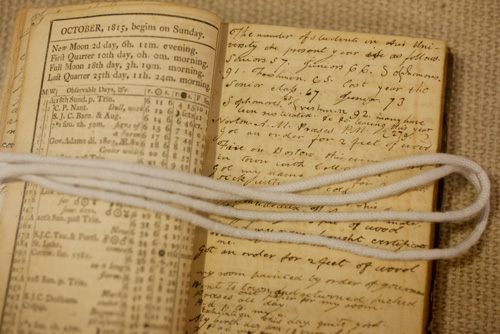

Artifacts in the exhibit’s four sealed cases tell the story. McCulloch’s letter is there, in his spidery undergraduate hand. Another, by undergraduate Horatio Newhall, Class of 1817, to his sister Lucy, recalls the “merry peal” of the same bells during a second celebration in March. (By then, the Treaty of Ghent had been ratified.) A diary by Robert B. Williams, Class of 1818, written in a tiny hand on the pages of a pocket almanac, recalls celebrations in Boston and Cambridge. Old maps detail the “seat of war,” the vast North American territory that was fought over.

The light touch of the war on Harvard did include a few inconveniences. Book deliveries from Britain were delayed for two years; the sloop Harvard, used to deliver firewood from Maine, was captured and burned, sending College officials scrambling for local wood; and roofing slate, normally from Wales, had to come from a New York supplier in order to finish Holworthy Hall in the summer of 1812.

This war between Britain and the United States is largely forgotten today, but it had important consequences. It assured that the Great Lakes would no longer be a site of war. It helped to shape Canadian identity (when two American invasions failed), and it prompted expansion of a newly respected U.S. Navy.

The war also gave rise to a few durable cultural touchstones: the fabled burning of the White House and the U.S. Capitol by British troops, the eventual national anthem “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the storied Battle of New Orleans that made Andrew Jackson a national hero, and the near-mythical power of the USS Constitution, now berthed in Boston Harbor. (Morison, the exhibit points out, was instrumental in preservation efforts for the ship, dubbed “Old Ironsides” in the war for the way its stout hull stood up to cannonballs.)

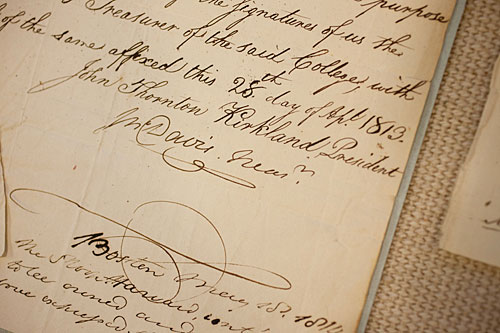

At Harvard, the greatest drama of the war came on June 6, 1814, the day the British waylaid the College-owned sloop off the coast of Maine. (This action was taken despite a customs affidavit — also in the exhibit — signed by Harvard President John T. Kirkland, assuring that the ship was used for peaceful purposes.)

The captain and crew were removed from the Harvard sloop without injury, and the ship was burned the next day. Alban Elwell, the brother of the sloop’s captain, Lewis Elwell, recounted the capture in a water-blotted letter. The captain, he wrote in strangled prose, “informed us that they Ware all Well, B[ut] he Writes that it is un Certin when they shall git home… .” (Captain Elwell, forcibly debarked at Halifax, was imprisoned for six months at HM Prison Dartmoor in the English countryside. Before the war’s end, about 6,500 American sailors were imprisoned there.)

There was no drama to the lost firewood; replacing it was just a matter of capitalism. The exhibit includes a newspaper advertisement, headlined “Wood Wanted,” by College steward Caleb Gannett. (The war and the loss of the sloop eventually provided a lesson in local sourcing. Less than two decades later, the College ceased buying wood from so far away and sold its post-war sloop.)

As for the missing books, look for the exhibit letter to Harvard treasurer John Davis from Thomas Gibson, an agent. The missive discussed the books “so long paid for & so long detained,” but it also nicely summed up New England’s relief at the end of the war. “I most sincerely rejoice,” wrote Gibson, “in the prospect of renewed amity between the United States & Britain & anxiously hope our future intercourse may no more be suspended.”

Then there was the Harvard Washington Corps, a student military drill unit revived during the war. The exhibit includes a coveted officer’s belt, signed and passed from one unit captain to another. (Though the exhibit is a no-touch affair, a reporter can attest that the belt’s leather is still buttery smooth.) Once during the war, uniformed members of the corps — denigrated as dandies by members of the regular Cambridge militia — were chased to the edge of Harvard Yard at bayonet point. (They were saved from harm by an elderly professor of Greek.)

“The college students were more patriotic” than their New England elders, wrote Morison, since many merchants and politicians saw the war as a violation of states’ rights. (A few even threatened secession.) The Washington Corps drilled twice a week, paraded quarterly on Cambridge Common, and survived beyond the war for at least 20 years.

The exhibit notes other Harvard connections to the war. Joseph Lovell, A.B. 1807, M.D. 1811, was a medical officer in the conflict, and later became the first surgeon general of the Army. Historian Morison got his start in the field by writing a Harvard Ph.D. dissertation on Harrison Gray Otis, who was instrumental in the Hartford Convention of 1814. It was there that some disgruntled New England Federalists, clamoring for states’ rights, threatened to secede from the United States.

In a later aside, future president Theodore Roosevelt, A.B. 1880, was still an undergraduate when he started research on his first book, “The Naval War of 1812” (1882). Historians, even 130 years later, regard it as one of the definitive histories of the conflict.