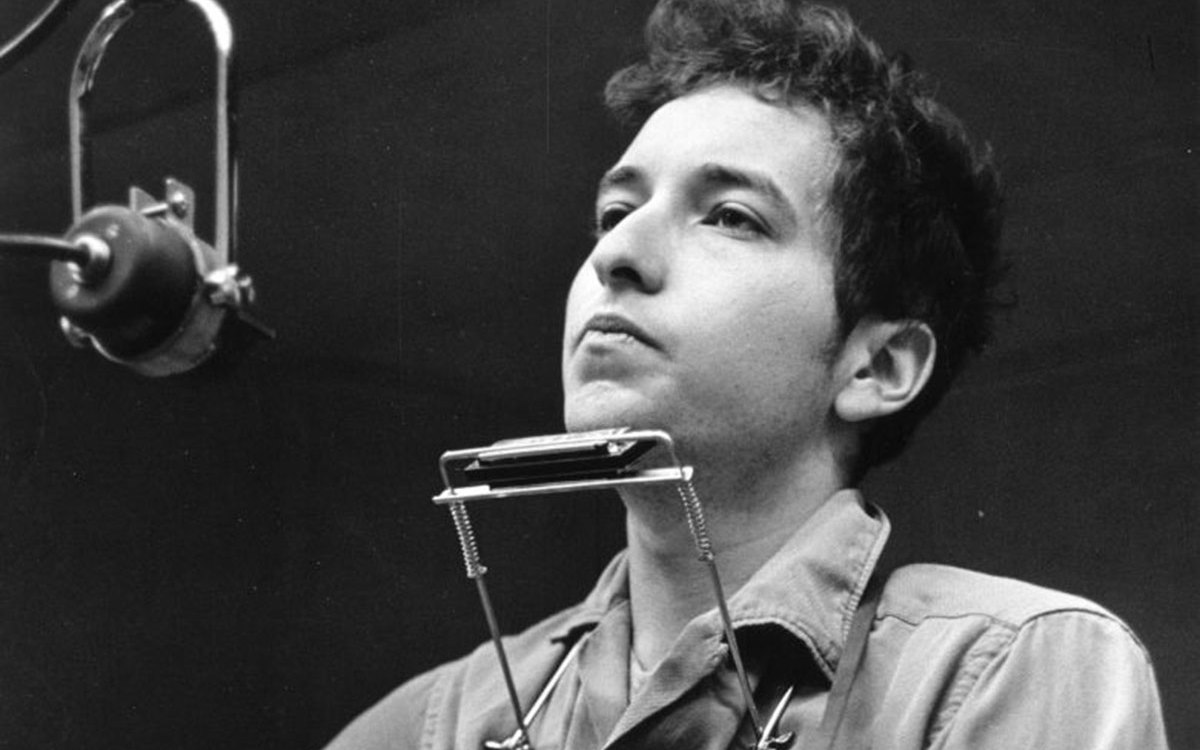

Edward Lloyd, exhibitions manager at the Carpenter Center, checks the lighting on a series of works by Josef Albers, “Homage to the Square,” which are included in “circa 1963.” The exhibit features works by 15 artists in vogue during the years of vinyl dinette sets, the Kennedy White House, and airplanes with ashtrays.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

At 50, a building still dares

A year of artistry will celebrate Le Corbusier’s Carpenter Center

Edward Lloyd was perched on a stepladder in the Sert Gallery, a third-floor exhibition space at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. He had just a few hours to put the finishing touches on “circa 1963,” a show of 15 artists in vogue during the years of vinyl dinette sets, the Kennedy White House, and airplanes with ashtrays.

Among the artists’ work in the bright little show is that of Roy Lichtenstein, Yoko Ono, Ben Shahn, and Josef Albers.

“It’s an unusual show for us,” said David Rodowick, the curator, the center’s interim director, the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies (VES), and the chair of the VES program. Most exhibits at the center feature works that go back a decade at most.

The exhibit, which is on display through Oct. 14, officially opens a yearlong celebration of the center, a modernist building on Quincy Street that turns 50 in May. It is the only building in North America designed by influential Swiss-born architect and artist Le Corbusier, and it was one of the last to be finished before he died in 1965.

The man called “Corbu” had to be talked into taking the commission by his friend Josep Lluís Sert, a Spanish architect who was dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) from 1953 to 1969. On Le Corbusier’s first visit to the Quincy Street site in 1959, he made two immediate decisions: that the new arts center would be placed at an angle, in part to accommodate tight space (less than an acre), and that its color scheme would contrast with the neo-Georgian, red brick structures that would surround it.

One early critic feared that the center would be “a white whale on stilts” set incongruously between the staid Harvard Faculty Club and the Fogg Art Museum. But Le Corbusier intended more than defiance with his only American building, which one admirer said was not a structure but a “manifesto.” He intended it to be a gesture of hope to a nation whose technical brilliance Le Corbusier admired, but whose soul he feared was being smothered by affluence. In a 1963 letter to Sert, about the center’s dedication, he reflected on his “horror of an affluent society without aim or reason.”

In the end, the center’s design acknowledged technology with its cubes and rectangles, but also invited whimsy with its curves. Its roof gardens and wild landscape plantings (later tamed) invited the countryside into the miniature city that Le Corbusier intended the building to be. The center’s central ramp and light-spreading glass invited spectators to observe art being made.

“It was meant to be a constant source of inspiration,” said Rodowick of the structure, which on viewing still seems surprising and experimental.

The center also embodies a fundamental passion that gripped Le Corbusier: the need to knit “head and heart,” said Rodowick, the need to assert that “creative practice itself was a kind of research activity.” To this day, the building anchors a locus of art making at Harvard. “We now have this arts corridor,” Rodowick said, connecting in one line the GSD to the art museums and the Carpenter Center.

Le Corbusier designed the center in an era when art and architecture had begun to blur. That confluence is well represented in “circa 1963.” The spotlighted artists still represent energy and daring, in line with Le Corbusier’s own building.

Rodowick, who has been planning the anniversary celebration with his staff for two years, did not want to create a display on the literal history of the building. He wanted an evocation of the era in which it was created, “a sense of what contemporary meant” five decades ago.

On his stepladder, Lloyd, the exhibitions manager at the center, was adjusting two lamps shining on six framed prints by Josef Albers, part of the experimental color series “Homage to the Square” (1965). Like many artists in the show, Albers had a long relationship with the center. His prints, like many, are part of the Fogg’s collections. Others works are on loan from the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Mass., including a screenprint — classically cartoonish —

by Roy Lichtenstein, “Sweet Dreams Baby” (1965).

There is also a photo of Yoko Ono on loan from the estate of Peter Moore, showing the waiflike future wife of John Lennon during a 1965 performance of her “Morning Piece” (1964). Pieces of sea glass, artifacts from the performance, are on display too, along with an advertising flier. In it, Ono mysteriously warns, “Wash your ears before you come.”

Experiments with media were part of the era, Rodowick said. So the show includes “Descending Light” (1960) by Gyorgy Kepes, a painting made with oil and sand on canvas. George Sugarman’s “Three Forms on a Pole” (1962), set in the center of the exhibit’s main room, is a sculptural color experiment in polychromed wood. “Age of Speed” (1961) by Albert Alcalay uses an old medium, oil on canvas, but its abstract, slashing colors represent the dash and verve of the border-busting art of the early ’60s.

After revisiting the past, the center will celebrate the future, starting with a series of fall events featuring young artists. The first is a co-exhibit by 2003 VES graduates Jesse Aron Green and Michael Wang in the main gallery, from Sept. 13 to Oct. 7, including works in video, glass, photography, and painting.

“They represent the very contemporary moment,” said Rodowick. “They represent the now, the very now.”

For a look at related events celebrating the Carpenter Center.