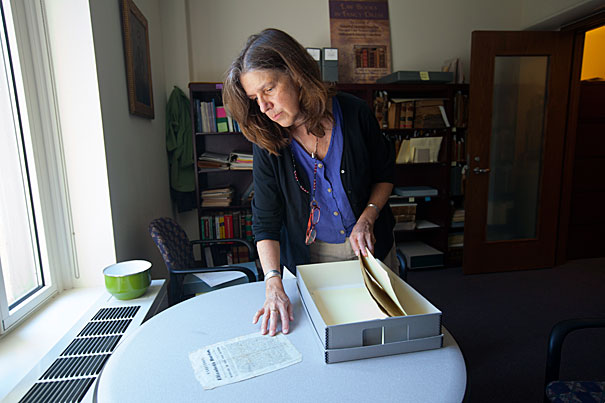

“They certainly pull you in,” said Mary Person, the archivist who catalogued most of the broadsides collection at the Harvard Law School Library. Person has looked at hundreds of broadsides and their dramatic stories of crime and punishment. “Human nature doesn’t change,” said Person of the broadsides’ popularity. “There is morbid fascination.”

Photos by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Guides to the gallows

Collection shows printed broadsides that accompanied executions

On Nov. 30, 1824, a London banker named Henry Fauntleroy was hanged in public outside Newgate Prison, one month after being sentenced to death for embezzlement. There were 100,000 onlookers.

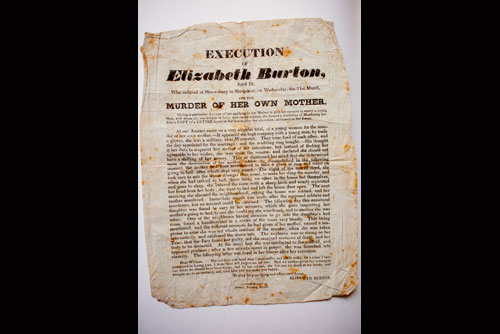

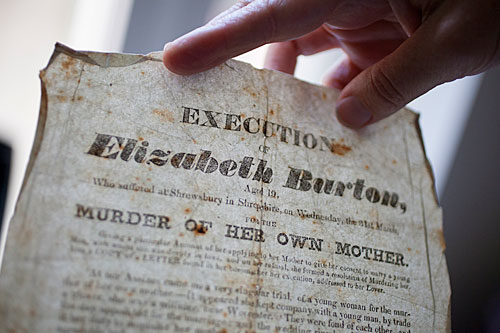

Many of those watching paid a penny each for a broadside printed just that morning. The single sheet describes Fauntleroy’s reaction when his appeal was denied. At the top of the broadside is a crude woodcut of a well-dressed man dangling from the gallows.

The Harvard Law School Library owns a copy of that broadside, along with four others about Fauntleroy, including an account of his execution. They are among 500 such artifacts in “Dying Speeches & Bloody Murders,” a collection of what scholars now call crime broadsides.

It is among the largest collections of its kind and the only one to be fully digitized. (That work was completed in 2007.) “It’s wonderful that people can sit anywhere in the world and look at these,” said Mary Person, the archivist who catalogued most of the collection.

Digital viewers rapidly get a sense of how times have changed. During England’s Bloody Code period, the number of crimes punishable by death escalated from 50 in 1688 to 220 by 1800. By then, a man, woman, or child could be sentenced to death for “uttering” (passing along fake documents), forgery (Fauntleroy’s crime), poaching, prostitution, insanity, petty theft, or fortune telling.

“They certainly pull you in,” said Person of the broadsides, printed on one side and often illustrated with woodcuts that were recycled for decades. She has looked at hundreds of broadsides and their dramatic stories of crime and punishment. “Human nature doesn’t change,” said Person of the broadsides’ popularity. “There is morbid fascination.”

She recalled the story of a young woman sentenced to hang for stealing a lace handkerchief, but who was pardoned. In fact, leniency was present too. Between 1770 and 1830, 20 percent of 35,000 death sentences in England were commuted — often changed to transportation to Australia, or impressment into the military. By 1823, only treason and murder required a mandatory death sentence, and by 1861 there were only five capital crimes left. The last British public execution took place in 1868.

An 1823 law set off decades of debate over reform, which even drew in literary lights. Writer Charles Dickens was appalled at public executions. William Wordsworth wrote sonnets in favor of the idea. Broadsides helped to sharpen the debate.

Law librarians at Harvard started collecting such broadsides in 1932 as a way to augment an extensive collection of British and American trial documents of the 18th and 19th centuries. The first major acquisition was a scrapbook jammed with newspaper clippings, broadsides, and other ephemera cataloging British public executions from 1820 to 1840. The anonymous compiler’s motives were clear: to record, he wrote, “innumerable proofs of the grossest barbarism” that capital punishment represented.

During the first half of the 19th century, “The general stance is that people of all classes read them,” said Ellen O’Brien, who teaches literature at Roosevelt University in Chicago. More than a decade ago, as a Ph.D. student in English at the University of Connecticut, she visited the Harvard Law School Library collection, and remembered “the strange little scrapbook” that piqued her interest.

“I discovered so much more variety and subtlety” than most broadsides scholarship suggested, she said. The visit inspired both her dissertation and her book “Crime in Verse” (2008). Crime broadsides are often more than moralizing tracts intended to keep the lower classes in their place, said O’Brien. They can be playful, spun out in verse, and subversive in intent, “clearly deviating from stock moral messages.”

O’Brien did her research not long after Harvard made its second major acquisition for “Dying Speeches,” in 1991, gaining 110 broadsides from a London collection. The archive now includes examples from 1707 to 1891. Such street literature — crude, direct, and often moralizing — that foreshadowed the lurid English-language pulp literature that followed, including the Victorian-era “penny dreadful,” the American dime novel, and, by the 20th century, modern crime magazines and comic books.

In Fauntleroy’s time, broadsides were in their heyday. By 1815 iron frame presses could be bought for as little as 30 pounds, ensuring cheap broadsides at 200 sheets an hour. Even provincial towns, with their own executions to note, were able “to produce their own literature,” wrote V.A.C. Gatrell in his 1994 study “The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People, 1770-1868.” Cloth-based paper and good ink had also by then transformed broadsides, which were first printed on fragile tea-paper with sooty lampblack ink. “The paper is gorgeous,” said Lesley Schoenfeld, public services and collections coordinator at the law library.

By 1855, a rising penny press in England spelled doom for crime broadsides hawked on the streets, and doom for the “patterers,” the vendors who used the singsong cadences of balladeers from centuries before. Those cadences helped keep verse a durable part of crime broadsides, which typically had a prose element too — details from the crime, the trial, and perhaps a lurid “confession.”

In the 1860s, O’Brien added, “People started saying: We need to collect these things. They’re disappearing.” A series of collecting impulses came together: record a dying cultural form, safeguard for the sake of collecting, and conserve for ethnographic interest. (Around the same time, Henry Mayhew tried to capture the sound of street vendors in “London Labour and the London Poor.”)

As a graduate student, O’Brien visited collections of broadsides in Britain, New York, and Providence, R.I. But it was at Harvard that she first realized that crime broadsides were “a very diverse representation — not all morally conservative and interested in simplistic representations of murder.” She also realized that the look of crime broadsides was diverse, and that they represented a “circulation” of energies through a culture, tracking between social classes. “The boundaries between high and low are not as fixed as we might think,” said O’Brien.

She said that the kind of insights she derived from “Dying Speeches” can be magnified, thanks to technology. “Now that they are digitized,” said O’Brien of the broadsides, “it’s opening the door for a lot more research.”