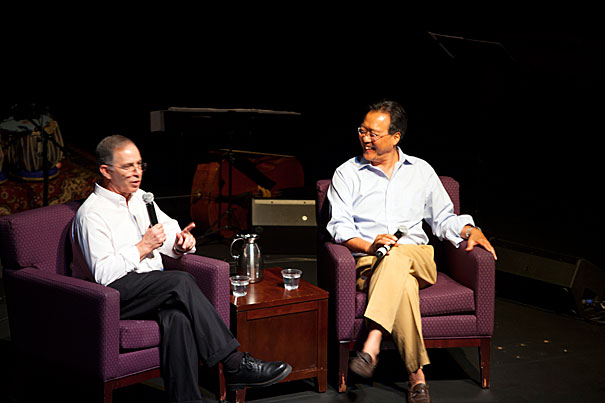

Steve Seidel, director of Arts in Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (left) and cellist Yo-Yo Ma, artistic director of the Silk Road Project, spoke at Farkas Hall in an event titled “The Arts and Passion-Driven Learning,” which explored how to encourage learning.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Inspiring as well as educating

Musicians, Ed School leaders probe teaching methods that turn ‘have to’ into ‘want to’

One of the first things students want to know when they meet perhaps the world’s most famous cellist is how often he practices, or, more specifically, how much he likes to practice.

Yo-Yo Ma admitted during a recent visit to Harvard that sometimes, even for the most accomplished musicians, practicing can feel like a chore. Ma told a crowd of educators and artists in Harvard’s Farkas Hall last Friday that when he asks his young questioners if, at times, playing for “20 minutes feels like eight hours,” they responded with a knowing groan. But when he inquired if, when they are deeply engaged with a piece of music, playing for “20 minutes can feel like 30 seconds,” the students smiled and nodded.

The difference between the two practice sessions, said Ma, involves the ability to find that “internal switch,” fueled by passion and engagement, that helps players to transition from feeling like “I have to do it” to “I want to do it.” Great educators need to help students tap into that sense of involvement in the classroom, he said at the opening of a two-day symposium aimed at helping teachers use the arts to inspire passion-driven learning.

Led by members of Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble and faculty from the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE), in collaboration with the School’s Programs in Professional Education, 83 teachers from around the world attended workshops and discussions that explored how the arts can help engage students across a range of subjects.

The event grew out of conversations involving Ma, members of the ensemble, and Steve Seidel, director of HSGE’s Arts in Education Program, following a three-day residency at HGSE by the ensemble in 2009. During that visit, Ma and his colleagues discussed their work with Silk Road Connect, a program that brings teaching artists — often members of the ensemble — into New York City middle schools to foster innovative teaching and develop interdisciplinary ties. The program culminates with a performance by the students and members of the ensemble. The residency led to an ongoing dialogue about how to bring that work to a larger audience.

“We only have the capacity to reach so many schools at any given time,” said Isabelle Hunter, program director of the Silk Road Project, a nonprofit inspired by the cultural traditions of the ancient Eurasian Silk Road trade routes that connected East with West, and the ensemble’s umbrella organization. “So we thought, ‘Let’s have an institute where people can come from anywhere around the world and take some of these ideas back to their own schools.’ ”

Paramount among those ideas is the notion of engaging students and building connections across fields of study. Great educators, like great performers, have to catch a student’s attention, and then take their learner on a journey made up of connections that transcend a single subject, said Ma. Great teachers, he said, “can take you to far away, and then somehow lead you right back to where you started.”

One example of Silk Road Connect’s interdisciplinary approach and arts engagement involves indigo. In 2009, students and their teachers in a number of New York City schools explored the pigment in depth, examining everything from its chemical components to its place in history.

They studied subject areas such as chemistry, art, music, history, geography, and economics through the lens of the bright blue dye, and collaborated with museums and institutions in New York to broaden their understanding of indigo and its many dimensions.

“A light switch goes on when you find a connection. But suppose you find 100 connections,” Ma said during the Friday evening discussion with Seidel. “Those connections keep you going both deeper and broader into a field.”

Ma and the ensemble members, who performed after the talk, agreed that collaboration in the classroom, as on stage, is a key to developing a successful learning environment. Students, like musicians, need to feel safe and supported in order to learn and grow.

While practicing newly commissioned works, members of the ensemble, who hail from diverse cultures and play an eclectic range of instruments from the violin to the Galician bagpipe, navigate cultural and musical divides, including the absence of written musical notation, something common among some Eastern musical traditions. To succeed, cooperation and communication are key.

Seidel recalled observing members of the ensemble working on a new piece. “It was one of the most astonishing learning environments I had ever witnessed,” he said of watching the ongoing dialogue and encouragement between the ensemble’s composer and its musicians.

“Part of being a transformative teacher involves creating a learning environment that is free of judgment and full of collaboration,” said Ma. The ensemble’s musicians and composers know that, he added, and are “going to make sure that nobody fails.”