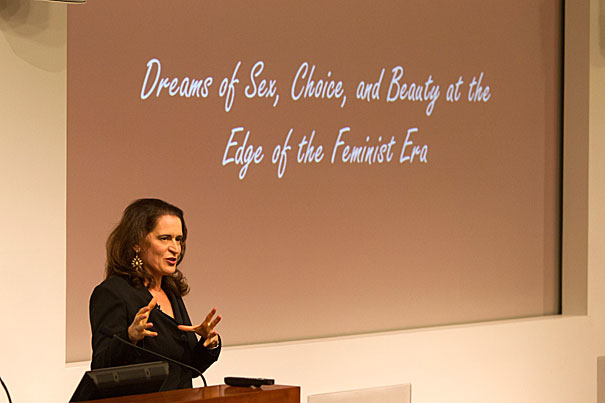

“We inherited a set of expectations that, at the moment, are actually dooming us to failure,” said Debora Spar, president of Barnard College, in a wide-ranging, lively talk on modern feminism.

Photos by Scott Eisen/Harvard Staff Photographer

Feminism without perfection

Reviewing gains at kickoff for 50th year of women at HBS

Harvard Business School (HBS) students gathered Tuesday to kick off a yearlong celebration of the 50th anniversary of the School’s first class of female M.B.A.s. After all, there was much to applaud. Women have gone from claiming just eight spots in that initial cohort to being 40 percent of the M.B.A. program.

But as the evening’s keynote speaker reminded the largely female group, women at the top of the ladder still face hurdles — including their impossible demands on themselves.

“We inherited a set of expectations that, at the moment, are actually dooming us to failure,” said Debora Spar, president of Barnard College, in a wide-ranging, lively talk on modern feminism.

The event, sponsored by HBS’s Women’s Student Association and open to the HBS community, was the first in a yearlong speaker series that will include a talk Thursday evening by Anne-Marie Slaughter, a Princeton professor who recently wrote “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” for the Atlantic.

This year, the School is honoring its gender-equality milestone “not by congratulating ourselves on a job well done, but rather by using the opportunity to explore the issues and challenges that women continue to face in business and in the world at large,” said Youngme Moon, Donald K. David Professor of Business Administration and chair of the M.B.A. program.

“The truth is we’ve come a long way, but we are not by any measure where we need to be,” Moon said.

Spar, a former junior faculty member at HBS, agreed. She spoke candidly about her perspective on feminism’s failing of women at the top of the ladder, drawing on her varied experiences from the male-dominated worlds of B-school and the investment firm Goldman Sachs (where she is a board member) to the all-female world of a women’s college. She drew from her recent Newsweek cover story on the topic and from her book due out next fall.

“This is an elitist book,” she said self-deprecatingly. Her goal, she added to knowing, nervous laughter, is to address “the people in this room: the people who have lives of great privilege to begin with, yet nevertheless still seem to somehow make themselves miserable.”

In higher education and in the working world, women have moved toward parity, though the percentage of women in executive leadership positions seems to top out at around 16 percent in most fields, from filmmaking to finance to government.

Meanwhile, at home, women still face a set of expectations as demanding as in the 1950s and ’60s, when Betty Friedan first railed against the housewife ideal. Though the data on this “second shift” work is somewhat heartening — men now perform a greater share of household chores and child care than they did in the 1990s — women work more hours than ever outside the home, more than making up for that gained time.

“We got out of the house, we got into the workplace, but we never stopped doing the housework,” Spar said. The result, she added, is that “free time disappears, sleep disappears.”

To knowing laughter, she showed images from women’s magazines of elaborate cupcakes and homemade bird feeders presented as “everyday” craft projects.

“This is what life as an average American mom is like!” Spar said. “You’re cutting pumpkins in half to make the birds happy.”

In addition, women in positions of power are expected to be thin, attractive, and in shape, she said. That upkeep “actually takes a lot of time to accomplish,” and could partially explain the 500 percent increase in cosmetic surgeries since 1997 and the prevalence of dieting rhetoric and eating disorders in America.

Anorexia is in part “about control,” Spar said. “It’s this same obsession with control that drives us to the stupid bird feeder and the cupcakes and the needing to feel that you have to have a perfect household and the perfect kids. I think this is part and parcel of the same set of grossly unrealistic expectations that particularly wealthy, successful, ambitious women in this country are laboring under.”

But regardless of income level, American women appear to be less happy than their mothers and grandmothers were in the 1970s, according to a 2009 study out of Princeton.

“New generations of women — including and, I think, beginning with my own — have turned away from feminism’s external and social goals, and we’ve instead turned in on our own lives,” Spar said. Paralyzed by unprecedented choice and the mantra that girls can do anything, many women try to excel at everything.

“It scares me,” Spar said. “We have to convince women themselves that feminism … is a social movement. It’s not a 12-step program toward personal perfection.”

“It’s supposed to be about working together,” she said. Though feminism may have “gotten us into this mess,” she concluded, returning to its communal origins “can show us the way out.”

Spar’s candid comments were a breath of fresh air, “especially at HBS, where we are all type A,” said Diana Sinyukova, an M.B.A. student, after the talk.

“HBS empowers you a lot, but there’s still the pressures of looking good and being attractive and doing everything perfectly,” said Sinyukova, who worked in construction and property investment management — heavily male industries — for a decade before coming to Harvard. “To actually have someone who’s successful say it’s all right not to be perfect, it’s like saying, ‘This is widely accepted. It’s OK!’ ”