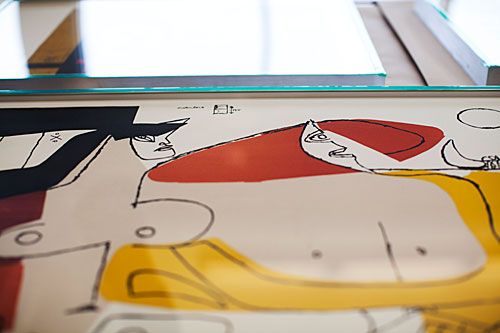

Paper conservators at the Weissman Preservation Center Adam Novak (left) and Christopher Sokolowski recently helped assess, repair, and reframe six Le Corbusier lithographs and one proof print from a Joan Miró etching. The artworks, most of them about 50 years old, came from the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The art of saving art

Weissman conservators repair Le Corbusier, Miró works for Carpenter Center

In the movies, a rescue mission involves men in body armor rappelling out of a helicopter, carrying machine guns.

At Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center, the rescuers are men and women in white smocks. Their missions involve rescuing paper objects from deterioration. They wield scalpels, soft brushes, wheat starch paste, and vinyl erasers.

Weissman conservators just finished an interesting rescue. They assessed, repaired, and reframed six Le Corbusier lithographs and one proof print from a Joan Miró etching. The artworks, most about 50 years old, came from the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Sun damage was one issue. For decades, the art had been exposed to daylight streaming through wall-size windows.

“The pink was quite pink,” said Debora D. Mayer, looking at Le Corbusier’s “La Femme Rose,” a 1963 work where the pink had faded to beige. “It certainly wasn’t so pale as this.”

Mayer, the Helen H. Glaser Senior Paper Conservator, last month showed visitors around the preservation center, where shallow steel sinks and trays of micro-tools and brushes are essential. “La Femme Rose” lay flat on a wide table. Other prints were arrayed nearby, like patients in triage.

Le Corbusier, the Swiss-born architect and artist, designed the Carpenter Center, which turns 50 next May. (A series of celebratory events is under way.) It is his only building in North America. The lithographs spent most of those 50 years on display in the ground-floor administrative offices. They were also in storage for a short time. So was the Miró, a proof for a poster advertising a 1978 exhibit on Spanish architect and Le Corbusier friend Josep Lluís Sert, who was dean of the Graduate School of Design from 1953 to 1969.

Building manager Dan Lopez told David Rodowick, interim director of the center, where the artworks had landed. Rodowick put them back on display, then got the conservation project started last December.

When prints or other conservation objects arrive at the Weissman, research is one of the first steps. “We all did a little study of them,” said Mayer, including a look at artist-appropriate framing styles.

Paper conservator Theresa Smith held up a book and opened to a page showing the central color element of “La Femme Rose” as it was originally — “redder than the print we have now,” she said.

To fix another Le Corbusier, “Femme à la Main Levée” (1962), Smith cleaned the surface with soft brushes and vinyl erasers; reduced creases with localized humidification; and repaired a tear at one edge with wheat starch paste. She moistened one area of black ink and tweezed off paper fibers stuck on top.

The existence of layers of ink on some of the prints was a revelation, said Mayer. Le Corbusier sometimes made as many as 12 color passes through the press for just one print.

From Le Corbusier’s “Les dés sont jetés” (1959), paper conservator Christopher Sokolowski removed a prominent brown stain using water, ethanol, and a suction device. “It’s supposed to look as clean and tidy as possible,” he said of the print, with its modernist lines. The point is to work on such art “as locally as possible,” he added. “That’s what we try to do with all of these — tread on them very lightly and very locally. It’s not always easy to do.”

Paper conservator Adam Novak had a similar issue with “Komposition Nr. 5 aus ‘Unité’” — a 1963 print with a water stain on the lower left corner. “The frame had rusted,” he said, “and the rust had traveled up.” It had also been damaged by broken glass.

The most damaged of the seven items was the Miró proof print. Sokolowski and intern Allison Holcomb dealt with two water stains and a tear. They fixed scratches consistent with contact with broken glass that had displaced both paper fibers and ink. They repaired a deep cut that had left a bright white line in the paper.

But the technical challenges were not overwhelming, said Mayer, and “it was a learning experience for all of us.” She mentioned Le Corbusier’s multi-pass printmaking techniques, his color-layering experiments, and the conservators’ research on framing protocols.

Through learning there was joy, as well. “We’re happy to work on anything” from Le Corbusier’s only North American building, said Sokolowski. “It’s an opportunity not many folks get.”

The six prints, along with the etching, are back at the Carpenter Center, their natural home at Harvard. “In relationship to the building, they’re quite wonderful,” said Edward Lloyd, the center’s exhibitions manager. “There’s no better way to show them than in this building.”

Where the work will be displayed is still a matter of discussion, he said. “Now that we’ve had them conserved, we don’t want to damage them.” They may hang for a few weeks at a time in the administrative offices, in a precisely calculated rotation to protect them from the east-facing windows.

Or they may go on display in B-04, a classroom sometimes used for public lectures, in which case they would be next door to the only other Le Corbusier artwork in the building: a large-scale tapestry hanging in the Lecture Room, which is now a theater for Harvard Film Archive screenings.

The building represents Le Corbusier’s genius on a monumental scale — and the lithographs his brilliance at smaller things. Together, said Lloyd, “it’s a matching aesthetic.”