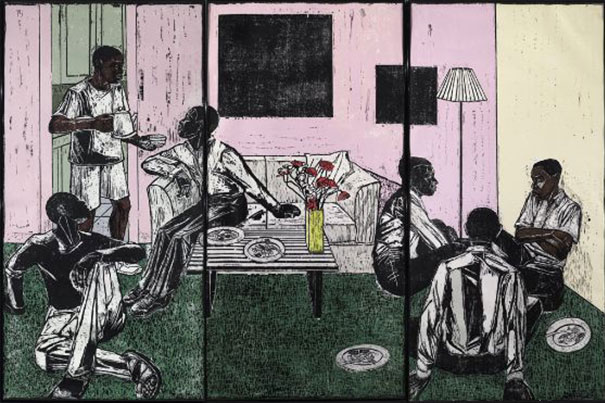

Artist Kerry James Marshall’s work “Untitled,” a 50-foot-long series of 12 large panels (detail above), will be on display at the Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum through Dec. 29. In a recent Harvard talk, Marshall described his work as being profoundly influenced by urban culture, the African-American experience, and civil rights.

Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums

The art of the possible

Kerry James Marshall outlines the importance of creative diversity to museums

One recent afternoon in the fourth-floor gallery of the Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, a young girl paused near a massive color woodcut by Chicago-based artist Kerry James Marshall.

As she gazed at “Untitled,” his 50-foot-long series of 12 large panels, several of which depict six African-American men relaxing in a living room after a meal, the girl said to her mother, “That looks like the president.”

“Perhaps such a statement suggests that expectations are shifting,” said Susan Dackerman, Harvard’s Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints, who recounted the child’s comments during a discussion with Marshall on Thursday at the museum.

Marshall said those shifting expectations reflect not only a change in the notion of who can hold the nation’s highest office, but who can create and be the subject of fine art. Marshall’s work is informed by his deep appreciation for the history of artistic expression, and profoundly influenced by urban culture, the African-American experience, and civil rights. With his work, he aims to transform the walls of the world’s art museums.

“If I keep going to the museum and only seeing a certain kind of image, or if your children keep going to the museum and only seeing a certain kind of image, then they might not be able to say … ‘That looks like Obama,’ ” said Marshall, who added that African-Americans as both creators and subjects of art are too often consigned to a type of “footnote.”

“What I want to happen when I go to a museum is that expectations of what you find in there are completely altered, so that it’s not commonplace to just see European paintings with European bodies, but it’s also as likely that you will see … black figures, Asian figures, or Hispanic figures.”

His recently installed “Untitled” offers viewers an “art history lesson” with its references to concepts like Fauvism, abstraction, and perception, said Dackerman. But the work also offers something more: images of African-Americans as the focus of art.

The work’s location in the museum amplifies that distinction. Approaching Marshall’s print from the adjoining gallery of 19th-century Western art, visitors first encounter “Odalisque with a Slave” (1839-40) by French artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. In the picture’s foreground, a semi-clothed, white woman reclines on a bed. In the background is a black figure, said Marshall, who “ends up in the shadows, peripheral to the narrative.”

“Somebody has to start placing those figures at the very center of what the work is about.”

Dackerman was captivated by Marshall’s work when she first saw it in a New York gallery in 1997, and she was determined to make it part of Harvard’s collection when she was hired in 2005. She visited the gallery every few months for the next year and a half until she finally convinced the dealer to part with it.

“I think it’s just really important to actively and in a conscious way be adding work by black artists to art museum collections, especially collections that have been built over a long period of time, like [those of] the Harvard Art Museums, that have this great depth.”

During his career, Marshall has placed African-Americans at the center of his work. His comic strip “Rythm Mastr” is driven by black characters and reframes the traditional vision of a blond-haired, blue-eyed superhero. His bold, suggestive paintings of African-American women are his answer to the iconic images in “The Great American Pin-Up,” a book that claims to cover the history of the genre, but only includes pictures of voluptuous white women.

“However problematic people might think the idea of the pinups are, you still can’t allow the field to be dominated by a single type of image and not have a counter-image that represents something else. That’s unacceptable.”

As a boy, Marshall perused every art book he could get his hands on. Later, an encounter with artist Charles White’s vivid works inspired by African-American life and social realism left him dumbstruck. “That was almost the end of the world,” he recalled when he realized White was alive and teaching on the West Coast. He was soon on his way to California to become White’s pupil.

Marshall combines meticulous study of the history of his craft with nuance, cultural perspective, and improvisation. His formula for success is to make yourself as informed about history and as self-conscious about your work as possible, get the skills and training you need, be ready to experiment, and then “just go for it.”

Asked by Dackerman why he tackled such a large-scale work as “Untitled,” Marshall blamed a man who inspired the art of the possible.

“Marcel Duchamp made me do it,” Marshall said, noting how the famous 20th-century surrealist and Dadaist encouraged artists to transform their studios into aesthetic laboratories. Marshall has embraced Duchamp’s experimental ethos, working alone and relying on ingenuity to solve his artistic dilemmas.

“I have to set up a situation … so I don’t have to ask anybody’s permission or ask anybody’s help in order to get it done.”

Such was the case with “Untitled.” Marshall cut the large blocks of wood for the work himself and created an intricate system that allowed him to lay sheets of 10-foot-long paper on the woodcuts without the help of an assistant. “There’s something about the challenge of trying to do that that matters a whole lot.”

The challenge of reshaping the art world requires that curators like Dackerman, said Marshall, are willing to acquire and display more diverse work. It also requires having more African-Americans on museum acquisitions committees, financially supporting and promoting such works, and being hired as curators.

As with the nation’s African-American president, said Marshall, “The goal is for it to be so commonplace that it’s not remarkable.”

“Untitled” is on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum through Dec. 29.