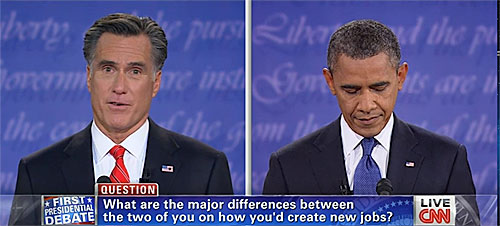

“[Romney] kept his body open and square, and he kept his head on straight,” said Nancy Houfek, a vocal coach at the American Repertory Theater, of the presidential debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. Houfek is an expert on how to speak, move, and act onstage.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Well, that’s debatable

Four performance experts offer tips for candidates’ next matchup

Nancy Houfek, Head of Voice & Speech at the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.), is an expert on how to speak, move, and act onstage. She had the same reaction to the first presidential debate that most viewers did: Mitt Romney flew, and Barack Obama flopped.

“Everything is performance now,” said Houfek, who teaches aspiring actors how to project their voices and deploy their bodies. Before there was television and the Internet, politicians were also actors of a sort, she said, but were more dependent on text and physical image. “I don’t think the Lincoln-Douglas debates were performance,” said Houfek. “They were content.”

These days, much of the content in a presidential debate is visual and kinetic. Houfek and three other Harvard experts on human behavior and performing offered their perspective on the first presidential debate and the two to come, including the one Tuesday night:

The public speaking guru

For more than two decades, Marie Danziger has worked to turn shy policy wonks into confident public speakers in her beloved Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) course “The Arts of Communication.” After the first debate, Obama came off more like the former than the latter, she said.

“I tell my students, ‘I want you to be as authentic as possible, but there’s one exception,’ ” said Danziger, lecturer in public policy and former director of the HKS Communications Program. “Even if you’d rather be dead than up there in front of that room, it’s your responsibility to fake it, to pretend there’s no place you’d rather be than talking about that issue to that audience. Your audience needs to feel your enthusiasm, your pleasure.”

In particular, Obama’s excessive note taking came across as “a little bit nerdy and undergraduate,” she said. “It makes the debate look like a tough academic exercise, rather than an enjoyable exercise of democratic deliberation.”

Danziger was less critical of — and more intrigued by — Romney’s initial performance, and wondered whether the Republican candidate was consciously using the Gish technique, a tactic developed by creationism advocate Duane Gish.

“It’s outlawed in some debate rules,” she said. “You keep bombarding your opponent with a cascade of arguments, some of which are false. And if you keep at it over and over again, it stupefies your opponent. There’s no way they can respond to them all. It gets them a little overwhelmed, a little confused and frustrated.”

Rather than attempting to respond to all of Romney’s arguments, Danziger said, Obama (and Romney, too) should stick to a “clear storyline.” She tells her students to “think of a triangle with your main idea in the middle and then three sub-ideas” as the triangle’s points. “The bottom line in the middle of your triangle is the most important, but you keep going back to the three sub-ideas as well.”

Her tip for Obama: Show your pleasure at this opportunity.

Her tips for Romney: Relax, and slow down.

— Katie Koch

The trial lawyer

“To become a great lawyer, you have to understand the rules that are required to control a courtroom, to avoid objections by your opponent, and to convince the judge that your questions are reasonable,” said Charles Ogletree, the Jesse Climenko Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and an Obama mentor.

Ogletree directs the School’s Trial Advocacy Program, an intensive three-week seminar that prepares students for the courtroom stage. The students learn how to listen, how to be clear and concise, and how to relate to a jury.

The same skills apply in presidential debates, said Ogletree, “or in any sort of forum where you are asked to show that you have both a sense of what’s at stake and the ability to articulate to folks who are waiting to be convinced.” Beginning students don’t effectively listen to their witnesses or opponents, he said.

But how you listen is equally important. During the first presidential debate, Ogletree said, Obama’s listening style made him seem detached.

“To take notes, to think about his answer, and to nod even when he disagreed” made him appear to some as professorial, unaware, and even unprepared. Ogletree teaches his students to recognize that the things they do can have a “lasting impact on the jury.”

Presidential candidates personalize issues as a way to connect with voters. In the same way, law students must try to personalize the story of their clients to the jury, and use simple, direct language. In Tuesday’s debate, Ogletree said he expects Obama to return to that style — which helped the president to get elected — of being “direct, strategic, plain-spoken, and sincere.”

His tips for Obama: Listen to your opponent. Speak plainly and simply. Be ready to respond to errors and misstatements.

His tips for Romney: Repeat your performance. Stay humanized.

— Colleen Walsh

The movement man

Shawn Lavoie is a lean, 6-foot, 4-inch-tall high school teacher, a sometime juggler, acrobat, tumbler, clown, actor, and dancer, as well as a one-time Obama impersonator, and a student in the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s (HGSE) Arts in Education Program. He drew on his performance background, extensive circus experience, and time spent at the famous Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theatre in California to view the debaters through a physical lens.

“We read body language,” said Lavoie. “The movements that people do and the way they carry their bodies is imbued with meaning.”

Lavoie noticed “striking differences” in the candidates’ movements and expressions during their Denver debate. Obama failed to make consistent eye contact with either Romney or with debate moderator Jim Lehrer. “Whenever he got a question, his eyes would be like Rolodexes. You could see that he was thinking,” said Lavoie, adding that Obama appeared too “inward-looking.”

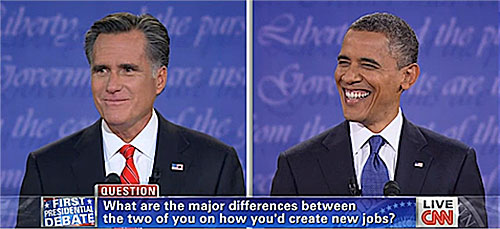

Obama also kept his hands fairly close to his sides, contributing to a feeling that he was “holding on.” In stark contrast, Romney made eye contact, frequently smiled, and kept his hands much wider apart, which made him appear to be literally and figuratively “reaching out.”

“I see Obama contracting his physical space, and Romney is expanding his physical space.”

In stage parlance, Romney was the breakout star of the show, while Obama looked a bit like an overwhelmed stand-in. Lavoie thinks Obama will do better when the podium is gone and he is free to move around during the second, town meeting-style debate. The more relaxed format should allow Obama to draw on his community-organizing background, said Lavoie, and his ability to connect with people.

His tips for Obama: Loosen up. Make eye contact. Go off script.

His tip for Romney: Keep your same debate coach.

— Colleen Walsh

The vocal coach

Nancy Houfek said Romney was the better performer during the first debate. “He kept his body open and square, and he kept his head on straight,” said Houfek, a former actress and model, and a 15-year A.R.T. veteran. “He looked directly at the camera, he looked directly at Jim Lehrer, and he looked directly at Obama,” in an overall effort that “engendered trustworthiness.”

Meanwhile, Obama tipped his head, kept his eyes down, averted his gaze, and wore a worried expression. “His whole body demeanor was not squared off and confident and present,” said Houfek. “It was much more compressed and bound.” Obama is capable of sparkling onstage. “He can do it. We’ve seen it,” she said. “He needs to be a slightly different version of himself. That’s what actors do.”

Before Tuesday’s debate, Houfek suggested that Obama play an hour of basketball, a sport that requires you to keep an eye on your opponent, catch the ball, throw it back, and tailor every move to the situation.

She would tell Obama to play “so that you’re loosened up physically, and so you’re thinking tactically, and so your energy is flowing up and out.” Actors warm up before going onstage, too, she said. They stretch, shake their hands, jump up and down, vocalize, and make faces.

Houfek praised Romney for using gestures well in the first debate, but she also warned him: Don’t let your body-forward style become aggressive, and don’t interrupt. “Let your fellow actors finish their lines,” she said. “Don’t jump your cue.”

Houfek offered similar advice to Obama: “Be fully present with your scene partner. Just as in a play, if you don’t like your scene partner, you don’t necessarily reveal that.”

Her tips for Obama: Loosen up, look up, and speak up.

Her tips for Romney: Keep that direct gaze, but don’t be a bully.

— Corydon Ireland