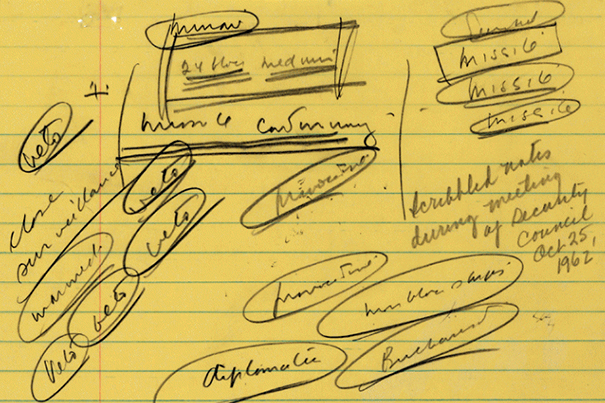

Detail of notes taken by President John F. Kennedy during a meeting of his security council on Oct. 25, 1962. Note the word “missile” written repeatedly in the upper right corner.

Courtesy of National Security Archive

When Armageddon loomed

50 years on, Cuban missile crisis still a case study in diplomacy

The black-and-white image is as familiar as it is iconic. The Oval Office photograph captures the solitude and solemnity of the U.S. presidency and the overwhelming sense that the young John F. Kennedy carried the weight of the nation on his ailing back.

The picture, taken from behind, shows Kennedy with his head bent and his hands outstretched on his desk. It actually was taken in February 1961, only a month after he took office, yet it would come to symbolize the pressures of the Cuban missile crisis that unfolded more than a year later. The 13-day standoff in October 1962 between the United States and the Soviet Union, which had installed nuclear weapons in Cuba, is when analysts say the world came closest to nuclear Armageddon.

The photo, christened “The Loneliest Job” by The New York Times, whose photographer George Tames snapped it, is part of a new website at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) marking the 50th anniversary of the crisis. The site is devoted to providing background on the conflict and encouraging reflection on the lessons learned from an event that eventually was viewed as a deft dance of diplomacy and an enduring teaching tool for current and future leaders.

“Because it was, I think everybody agrees, the most dangerous moment that human beings have lived through and survived so far, it has a compelling character,” said Graham Allison, HKS’s Douglas Dillon Professor of Government and director of its Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. “We are very interested as a center and as a School in what lessons you can learn from history that you might apply to help deal with current problems; I think the Cuban missile crisis is an excellent illustration of that.”

The site draws from the Belfer Center’s trove of material about the crisis and from other sources. It includes a historical timeline, archival photos, original documents, video clips, an assessment of present nuclear fears, and teaching tools for educators, such as a lesson plan with guiding questions, worksheets and simulations. It also includes lessons learned by key players involved in the incident. Visitors to the site are invited to offer their own lessons gleaned from the dangerous stalemate. In collaboration with Foreign Policy magazine, the Belfer Center is sponsoring an essay contest for students in grades six to 12, for the public, and for international-affairs scholars and practitioners.

“The website is designed around the lessons and the learning opportunities,” said James Smith, the Belfer Center’s director of communications, who, together with a team led by Arielle Dworkin, the center’s digital communications manager, helped to develop the site. “We want to remind people that the lessons are still relevant, that there are current crises where the key lessons from the original Cuban missile crisis are still very useful today.”

Allison, an authority on the crisis, wrote in the publication Foreign Affairs in June, “The lessons of the crisis for current policy have never been greater.”

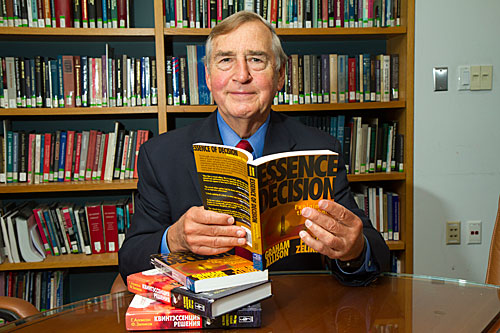

His 1971 treatise “Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis” is widely credited with transforming the field of international relations. (Based on the release of new material about the crisis, he rewrote the book in 1999 with author Philip Zelikow.) The work explores the nature of the crisis from three decision-making perspectives: the rational actor, governmental politics, and organizational behavior.

During an interview in his Harvard office, Allison offered his take on the lessons from the crisis. The first is that nuclear annihilation is possible. In the aftermath of World War II, tensions escalated between the United States and the Soviet Union. As worries and distrust mounted between the two superpowers, so did nuclear arsenals, bomb shelters, and public service announcements that trained countless schoolchildren to take refuge under their desks in a nuclear attack. The crisis in Cuba looked like a struck match.

From the outset of the conflict, said Allison, it was clear that both President Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev were “willing to take action that they knew could end in a nuclear war.”

Secondly, the world learned that such disaster was preventable, thanks to what Allison calls a “combination of wise policy and good fortune.” Both leaders, he said, “having peered over the precipice and seen and felt what a nuclear war could actually mean, determined first to escape the brink by actions both of them took … and never to go there again.”

Their decisions had lasting repercussions. The choices the two men made led to what Kennedy referred to at the time as the “precarious rules of the status quo,” said Allison, to which each subsequent generation has strictly adhered. The U.S. and Soviet leaders who followed assiduously avoided provocations and “surprises that could have ended up in confrontations that could then move inexorably to a nuclear war.”

Allison said that while the threats of nuclear terrorist attacks that could devastate a city remain horrific, they are of a scale far smaller than during the Cold War. Then, the world faced a “genuine nuclear war that might have succeeded in extinguishing the species on Earth.” Today the risk of that kind of nuclear annihilation, he added, “has now shrunk to nearly zero.”

Of course, the world still has nuclear-armed states to contend with, including the worrying case of Iran, a country many fear is well on its way to developing nuclear weapons. Allison has called the situation in Iran “a Cuban missile crisis in slow motion.” Iran’s leaders insist its interest in nuclear technology is purely to generate energy, but critics point to Iran’s use of deep underground centrifuges used in the production of nuclear fuel as evidence that the country is ramping up its ability to enrich uranium and develop a nuclear weapon.

In dealing with Iran, the lessons from the Kennedy administration remain relevant, said Allison. When approaching negotiations with Iran’s leaders, the United States administration should ask itself, “What would Kennedy do?”

According to Allison, Kennedy wouldn’t rest until he had the best choice available. Kennedy’s advisers offered him an either-or scenario, to attack Cuba or acquiesce. But Kennedy refused both, judging each option “as bad as the other.” Instead, he “concocted a very imaginative but strange combination,” said Allison, consisting of a public deal (remove your weapons, and we will not invade Cuba), a private ultimatum (you must respond within 24 hours, or we will conduct action ourselves), and a secret sweetener (if the missiles in Cuba were withdrawn, within six months the United States would remove its missiles from Turkey, near the Soviet border).

President Barack Obama’s advisers are likely offering him similar advice on Iran, said Allison: “Either you are going to attack Iran to prevent it from acquiring a nuclear bomb, or you are going to acquiesce to Iran becoming a nuclear-armed state.”

“The United States will simply have to accept the unacceptable, the recognition that Iran now is capable of enriching uranium and building a bomb,” Allison said, but then added that Washington also can craft a deal reminiscent of Kennedy’s. The Obama administration, Allison said, “should demand as a price for that the supreme leader’s solemn commitment that Iran would never develop a nuclear weapon, combined with transparency measures that would give the United States maximum confidence that they are not cheating, and thereby minimize the likelihood that they decide to cheat, and a credible threat of devastating consequences if Iran violates these terms.”

If another foreign conflict is any indication, it appears that Obama may have already learned the lessons of the Cuban crisis. Journalist Michael Lewis’ profile of Obama in October’s Vanity Fair describes how the president grappled with the growing humanitarian crisis in Libya last year as Moammar Gadhafi “and his army of 27,000 men were marching across the desert toward a city called Benghazi and were promising to exterminate some large number of the 1.2 million people inside.”

During a meeting of top advisers to explore what Gadhafi might do and how the Pentagon might respond, Lewis wrote, “The Pentagon presented the president with two options: establish a no-fly zone or do nothing at all.” In the end, Obama, after taking the unusual step of turning to junior staffers in the room to solicit their opinions, left the meeting, but not before “he gave his generals two hours to come up with another solution for him to consider.”

Like Kennedy 50 years earlier, Obama took the third option — the one that only emerged after he insisted on finding another way.