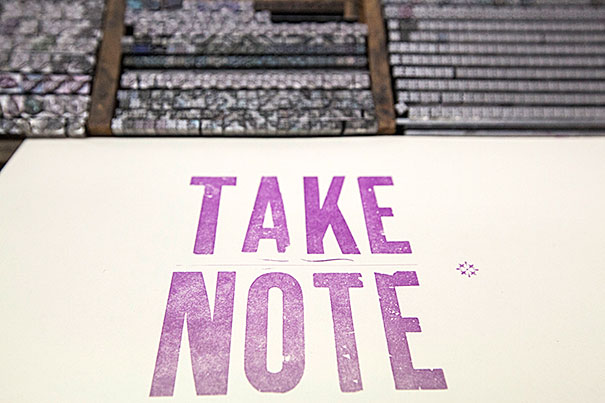

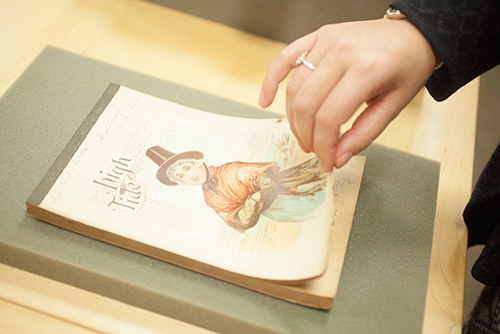

“Take Note,” a symposium organized by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, explored the art and importance of effective note taking. As part of the symposium, participants visited the Bow & Arrow Press at Adams House (pictured) and the Harvard University Archives.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Note taking in a clickable age

The shifting nature of an age-old way of recording knowledge

An observer only had to glance around the Radcliffe Gymnasium to understand the tactile nature and evolving techniques of the subject, literally, at hand. Some people tapped away on laptop computers, others used iPads to jot down thoughts. Many fumbled with the small buttons on their smartphones. A determined few resorted to paper and pen, even pencil.

The note takers were all part of a daylong symposium aptly titled “Take Note,” and organized by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study earlier this month to explore the art and importance of effective note taking. The conference, the culmination of a four-year effort at Radcliffe to examine the tradition of books and their prospects in a digital age, brought together scholars from a range of disciplines.

In her opening remarks, Radcliffe Dean Lizabeth Cohen discussed the importance of notes in her work and how her own style of note taking has evolved throughout her career. A social historian, Cohen called the notes that she finds in archives “a one-way mirror into people and their thoughts, and they help me construct the past.”

Like countless scholars, Cohen also relies heavily on the notes she takes during her research to help her shape the ideas and arguments that form the basis of her writing. She said her note taking underwent a transformative shift at the recommendation of a graduate school professor, who encouraged her to write directly in the books she was reading.

“ ‘A book is a tool,’ he would say. ‘Make it your own. Be in dialogue with what you read,’ ” recalled Cohen. So she took the plunge. Careful to avoid writing in first editions or borrowed books, over time she has amassed both an extensive personal library and an archive “of how, over the years, I have engaged with what I have read.”

Through the centuries, note taking has taken various and even unusual forms, explained Peter Burke, emeritus professor of history at the University of Cambridge, who offered the crowd a perspective on the past and future of note taking. While some early scribes used rolls of wax or sheets of paper for their notes, others took advantage of something else altogether. “Starched shirt cuffs … were a wonderful surface for pencils in their day, and gave rise to that wonderful expression ‘speaking off the cuff,’ ” said Burke.

The session also raised an important question, one that attendees and panelists agreed lacks a definitive answer. While many participants acknowledged that notes will continue to be an important part of the digital age, they were less in agreement about how private or public those notes should be. In the digital realm, privacy rights are increasingly a concern, yet those with Internet access can blast their random musings into cyberspace for anyone to see. Because of that, the question arises: Should note taking be confined or redefined? If so, how?

For its part, Radcliffe embraced the concept that notes should be shared. The event included a vivid online exhibit compiled of note-taking materials from Harvard’s libraries and museums. Visitors to the site were invited to add their own electronic note. The symposium produced a lively Twitter feed, where Radcliffe encouraged participants to share their comments or pictures of the notes they were taking, providing a steady stream of feedback and questions for the panelists.

For instance, a former fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society, David Weinberger, tweeted, “Collaborative notetaking via etherpad or GoogleDocs etc. is often a great way to go. Fascinating to participate in, too,” during an afternoon presentation that explored digital annotation tools. The session’s panelists agreed that such high-tech tools remove barriers to sharing information and that collaborative open-source platforms can often result in an enhanced product.

“Knowledge,” said Bob Stein, the founder and co-director of the Institute for the Future of the Book, a think tank that tracks the evolution of “intellectual discourse from the printed page to the networked screen,” “is created by groups of people.”

But one conference attendee balked at the thought of sharing her thoughts with the public.

“I was struck by the request that we send our notes into Radcliffe because my reaction was, ‘You know, my notes are really none of your business. My notes are my private thoughts, my private collaborations.’ Until I am dead, I don’t really need other people looking at them.”

The question of public versus private notes dates back hundreds of years to the days when parishioners captured sermons in their small, erasable “table books,” where they jotted down pithy lines, or even an entire address that they would sometimes publish later for wider public consumption, said Tiffany Stern, professor of early modern drama at the University of Oxford.

Similarly, many theatergoers, eager to keep pace with the expanding vocabulary of the time (helped along in large part by William Shakespeare, who frequently introduced new words into his works) would also scribble down a new joke or word in their table books while attending a play by the Bard, said Stern. “If you went to plays, you learned a new word and learned it in context. … It was a little present for you. You could go out with a new word and start using it.”

As a primer to the symposium, attendees explored various forms of note taking on display in the University’s libraries and museums the previous day. At the Harvard University Archives, librarians and archivists had culled the University’s rich resources to mount a small exhibit of material like College Book No. 1, a long, leather-bound volume containing some of the earliest records for Harvard’s two governing boards, the Harvard Corporation and the Board of Overseers. Inside the book, on a page containing minutes from a Corporation meeting held in 1643, is the first appearance of the Harvard College veritas shield. The exhibit included the shorthand notebook of stenographer Amy Hutchins, who used a cryptic system of strokes and squiggles to meticulously capture some of the 1895 correspondence of Harvard President Charles W. Eliot.

Harvard’s Public Services Archivist Barbara Meloni said her favorite item in the collection was the set of typed pages from the archive of political journalist, author, and historian Theodore H. White that recounted his dinner at the White House in 1963. The Harvard graduate recorded the experience in amusing detail and even recalled the antics of the young John Kennedy Jr., who “was shouting ‘monkeyhouse, monkeyhouse,’ as soon as he saw his dad.”

“It’s such an intimate look at a particular moment in history,” said Meloni. “It’s history, right there in your hands.”