Holmes’ suite home

Law library launches massive database on famed American jurist

On the first Sunday in March of 1931, about 500 people gathered in Langdell Hall at Harvard Law School to listen to a CBS Radio broadcast by Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the ambitious, egotistical Civil War veteran and Harvard graduate (A.B. 1861, LL.B. 1866) who pioneered the concept of legal realism. The law was “a practical weapon,” Holmes believed, and legal cases are best judged according to realities rather than abstractions.

The radio address celebrated Holmes’ 90th birthday, one of many moments of adulation that spring that amused and pleased him — so much praise, he said, even though “self is so near vanishing.”

Holmes should not have worried about his “self” vanishing. He remained a household name after his death. He was the first Supreme Court judge to merit a biographical movie (“The Magnificent Yankee,” in 1950). Besides being a judicial pioneer, his many aphorisms outlived him. One is especially apt today: “I like paying taxes. With them I buy civilization.”

Now there is another reason to remember the fiercely mustachioed Holmes: the Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Digital Suite, which went live on the Web Tuesday, the culmination of years of teamwork at the Harvard Law School Library (HLSL).

In a first for the library, the site aggregates multiple archival holdings into a single, hyperaccessible digital suite that anyone with a computer can search, browse, and tag. (The library uses the word “suite” to mean a collection of collections.) In the new suite, users can search and browse across five manuscript and three visual collections.

“We’re not making anything newly available through this. But the access is so greatly enhanced now. We’re making this convenient,” said Margaret Peachy, curator of digital collections at the library.

The new suite replaces and expands the library’s digital collection on Holmes. It not only aggregates manuscripts and images, but it offers simple and advanced searching, facilitates browsing, and offers links to like-minded searchers.

Who are the expected users? “Anybody with a computer who comes to this site,” said Stephen Chapman, project manager in the library’s digital lab.

Holmes used to say that a person’s education begins 200 years before his or her birth — that is, your heritage is part of who you are. Holmes had parental roots reaching back to New England’s first families, including those named Oliver, Wendell, and Holmes. On his father’s side he was related to Anne Bradstreet, English North America’s first published poet.

A life that was a timeline of U.S. history

As a boy, Holmes had his own view into the far past, and as an old man recalled his grandmother’s story of escaping the British when they invaded Boston during the American Revolution. (She left behind her doll.) When Holmes was born, in 1841, there were 26 U.S. states, Texas was an independent republic, and Boston had fewer than 100,000 people. During his life, he witnessed two major wars and five catastrophic financial upheavals. He died in 1935, during the Great Depression, with World War II on the horizon.

Holmes was a judge from 1882 to 1932, first on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and then, starting in 1902, on the U.S. Supreme Court. He wrote 1,290 opinions for the court majority in Massachusetts, his crucible as a jurist, and took part in 5,950 cases during 30 years on the U.S. high court. (Most of these decisions are available for viewing in the Holmes suite.) To learn the art of innuendo in writing opinions, he once advised a young lawyer to read risqué French novels.

A Boston Brahmin to the bone — a snob, in fact — Holmes was worldly and witty. He was known in Washington, D.C., for his frequent visits to burlesque houses and for his eclectic reading lists, which mixed (in 1927, for instance) forays into Vernon Parrington and Samuel Eliot Morison with an Anita Loos novel called “But Gentlemen Marry Brunettes.” In 1933, he celebrated his 92d birthday by drinking several glasses of bootleg Champagne. “I do not deal with bootleggers,” Holmes assured his guests, with tongue in cheek. “But I am open to corruption.”

Throughout his life, the Civil War veteran used martial metaphors and carried his daily lunch to the Supreme Court in a tin ammunition box. (That artifact is among more than 150 items in the newly organized Holmes Object Collection, which also includes his gavel, his Civil War gun belt, and his death mask.)

So the new digital suite, which was funded by Norman B. Tomlinson, J.D. ’51, functions as a kind of time machine for scholars of history, literature, law, and culture. Casual users will discover a lens through which they can watch the United States move from the provincial to the modern.

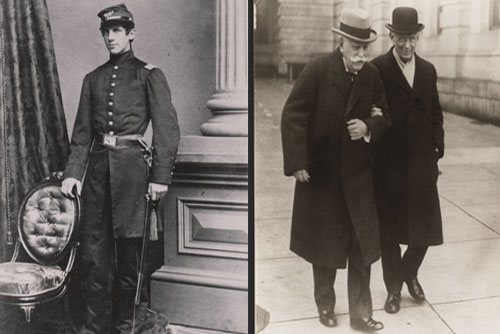

To aid searches, the suite is divided into six phases of Holmes’ life: youth, Civil War service, early career, judicial career, personal life, and later life. A visitor can move from the fresh-faced boy posing with his siblings, to the erect soldier of 22, to the jurist in his prime at work behind a desk, to the elderly Holmes, stooped as he walks beside Supreme Court colleague Louis Brandeis.

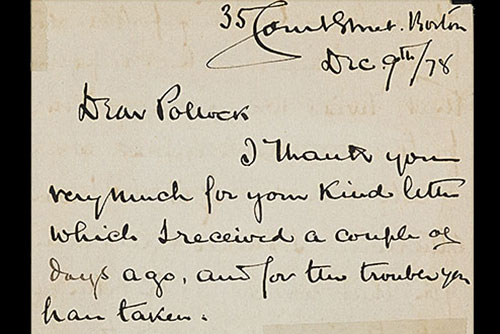

The suite’s five manuscript collections indicate the depth and chronological range of the holdings. These include the John G. Palfrey (1875-1945) Collection of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Papers, 1715-1938; the Mark DeWolfe Howe Research Materials Related to the Life of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., 1858-1968; the Edward J. Holmes Collection of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Materials, 1853-1944; the Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Addenda, 1818-1978; and the Letters from Holmes to Lady Castletown Small Manuscript Collection. (Holmes, during a long relationship with Lady Clare Castletown of Ireland, called her “my Hibernian.”)

A penchant for flirtation, privacy

That last collection gets to both the heart of Holmes’ penchant for flirtation and his obsession with privacy. (He folded his letters queerly, so nothing could be read from outside the envelope.) From the end of the Civil War on, he insisted to friends that they destroy any “illuminating documents.” Many of those friends disobeyed, and history is better for it.

The digital suite is built on the library’s open-source, 3D technical platform, with software designed by Web developer Andy Silva. (The description “3D” stands for the Discovery and Delivery of Digital Collections.)

The heart of the 3D concept is access and enrichment, including an invitation to users to add tags to the Holmes material they peruse. “Through crowdsourcing, we want to make our material better,” said Chapman, though spam filters will be in place too. “Our position is one of general trust.”

User tags will be posted immediately in the suite’s search index, but will be distinguished from curatorial tags and reviewed periodically.

The initial documenting, digitizing, and tagging started in 2009. Chapman and Edwin Moloy, curator of modern manuscripts and archives at the library, managed workflows and oversaw the project. Peachy rearranged and processed the historical collections. Digital projects assistant Lindsay Dumas produced hundreds of thousands of tags. Craig Smith, a former digital projects assistant, prepared more than 2,000 manuscript folders for digitization. Eldra Walker, a candidate in the joint Graduate School of Design/Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Ph.D. program, helped to tag hundreds of items. Mindy Spitzer Johnston, former curator of digital and visual resources, cataloged the Civil War materials. Harvard Library’s Imaging Services handled the digital photography. Nicholas Cochrane and Malisa Kuch of SwissFish designed the suite’s website and key components of its browsing functions.

Other digital collections at the library are lined up for future digital suites, including one on war crimes and another on Harvard Law School’s history. The suites will have the same robust browse, search, and tagging functions as the Holmes suite, as well as forums for user communities.

In assembling the Holmes suite, Peachy was struck by his Civil War letters to his parents, and by the timelessness of their sentiments. Some of them, she said, “could be sent home from Afghanistan.” Chapman was intrigued by the postcard collections that Holmes amassed during trips to Europe.

“At the end of the day, this is a narrative story of a human being and a life,” said Chapman. “And this is an extraordinary life.”