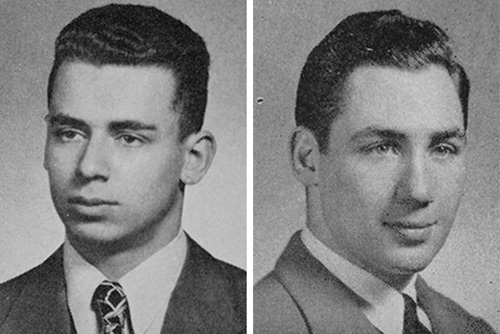

In “Nothing But a Man” (1964), Abbey Lincoln (left) and Ivan Dixon play a young married couple facing injustice in the Jim Crow South.

Photo courtesy of Harvard Film Archive

Nothing but a breakthrough

Landmark 1964 film about race by two Harvard grads launches Film Archive’s season

In the summer of 1963, two Harvard graduates teamed up to shoot a landmark independent feature film about the Jim Crow South. “Nothing But a Man,” released in 1964, was among the first American movies to cast black actors as the leads in a vehicle intended for a general U.S. audience.

The 92-minute film made its creators, director Michael Roemer ’49 and cinematographer Robert M. Young ’49, cinematic pioneers. Until that time, black actors either had been relegated to secondary roles in mainstream movies or had appeared in what were called race films, features that were shot between 1915 and 1950 and were marketed to black-only audiences.

With the film’s 50th anniversary approaching and its Harvard provenance, the movie was a natural to lead off the 2013 season at the Harvard Film Archive, said programmer David Pendleton. But the immediate impetus, he said, was the recent release of a restored 35 mm print by the Library of Congress. (Screenings run from Jan. 11 to 20.)

“Nothing But a Man” also stands out as a truly independent film. It was written, produced, and shot outside during an era when Hollywood’s studio system kept a grip on nearly everything made for the screen. The movie about a rough-edged rail worker who falls in love with a preacher’s daughter broke some artistic boundaries, too. It was shot in black and white in a naturalistic, documentary style that was part newsreel, part film noir, and part ethnography. (Right out of college, Roemer apprenticed with Louis de Rochemont, creator of the iconic “March of Time” movie newsreels.) The Roemer-Young film featured settings of black life and its difficulties. The film’s visual style is like an animation of a Walker Evans photo album.

“Nothing But a Man” was also the first film to feature a Motown score. Attorney George Schiffer ’53, a friend of Roemer, was general counsel for Motown Records from 1959 to 1975. He handed the young director a stack of 45s one day, and the resultant soundtrack included Mary Wells, Stevie Wonder, and Martha and the Vandellas.

The film is also memorable for its cast, most of whom were neophyte black actors just beginning a rise to stardom. Julius W. Harris, a male nurse and onetime bouncer, had never acted before, but went on to make more than 70 films. The movie also featured a very young Yaphet Kotto in only his second film.

The man who played the laconic and tough rail worker, summing up black male frustrations of the era, was Ivan Dixon, best remembered today for his later role in television’s long-running “Hogan’s Heroes.” His co-star who played the steady and loving schoolteacher was Abbey Lincoln, whose only previous film appearance had been as herself in “The Girl Can’t Help It.” Lincoln went on to a long career as an actress and jazz singer, and was often compared to Billie Holiday.

“Nothing But a Man” won a pair of prizes at the 1964 Venice Film Festival, and drew raves at the New York Film Festival. But critical acclaim was not followed by box office success. After it tanked in American theaters, the movie found a quiet second life as a 16 mm offering screened in black churches, community centers, and classrooms.

When it was re-released in 1993, the film finally turned a profit. Its artistic acclaim also held steady. By the following year it had been listed in the National Film Registry.

Inspired by a 1933 play, and crafted into a screenplay by Roemer and Young, the movie was made on a budget of $250,000. (Everyone — cast and crew alike — made $100 a week during filming.) It was shot on location in Atlantic City and in Cape May, N.J., because filming in Alabama, the purported setting, would have endangered those involved. To be able to evoke the mood and settings, Roemer and Young spent three months in 1962 on a research trip to the segregated South. Young later described the journey from one black safe house to another as the Underground Railroad in reverse.

“Nothing But a Man” came out when turmoil and violence peaked over issues of race and citizenship. Young was most fervent about the civil rights message in the film, which includes stomach-churning scenes of injustice meted out on the Alabama color line. But Roemer, a son of a German Jews, was more interested in how poverty and social stresses can unravel a marriage, parenthood, and even character. Roemer’s well-off Berlin family had lost everything when the Nazis swept into power, stripping Jews of their rights, safety, money, and job prospects. He later said he identified with the movie’s rail worker, whose righteous sensibilities bounced him from job to job.

“If you’re unemployed, you don’t feel like you’re a man; at least my generation didn’t,” Roemer told the New York Times in 2004, when a 40th anniversary DVD was released. “That’s not black; that’s all of us.”

But the film is also Roemer’s homage to the redemptive powers of marriage and fatherhood. In the last scene, the rail worker returns home, embraces the schoolteacher, and says, “Baby, I feel so free inside.”

At age 11, in 1939, Roemer was sent to England, one of 10,000 European Jewish children rescued in the Kindertransport. He studied at the Bunce Court School in Kent, a school for dispossessed children. Many of those children eventually turned to careers in the arts.

During Roemer’s Harvard College years, Lamont Library was built, weekly board went up to $11.50, Latin was eliminated as a requirement for the A.B., Cambridge got its first parking meters, and the Chicago Tribune dubbed Harvard “a hotbed of communism.”

He became an English concentrator, joined a Zionist group, did dean’s list work, and lived at Kirkland House. But the young German’s real legacy at Harvard involved directing a pioneer film, “A Touch of the Times,” which may be the first feature film produced at an American college.

Made for Ivy Films, a new club, this 16 mm fantasy comedy, which premiered in the fall of 1949, was about factory workers who gave up labor to fly kites. It took two years to make, more than 300 hours to shoot, and cost $2,300. Cast members kept graduating or getting placed on probation, Roemer said later, so the lead actor had to be replaced five times.

In 1966, Roemer started teaching film at Yale, which he still does today at age 85. Young, who is 88, is still involved in cinema as a screenwriter, director, cinematographer, and producer on the West Coast. Among the leading actors in “Nothing But a Man,” however, only Kotto is still alive.