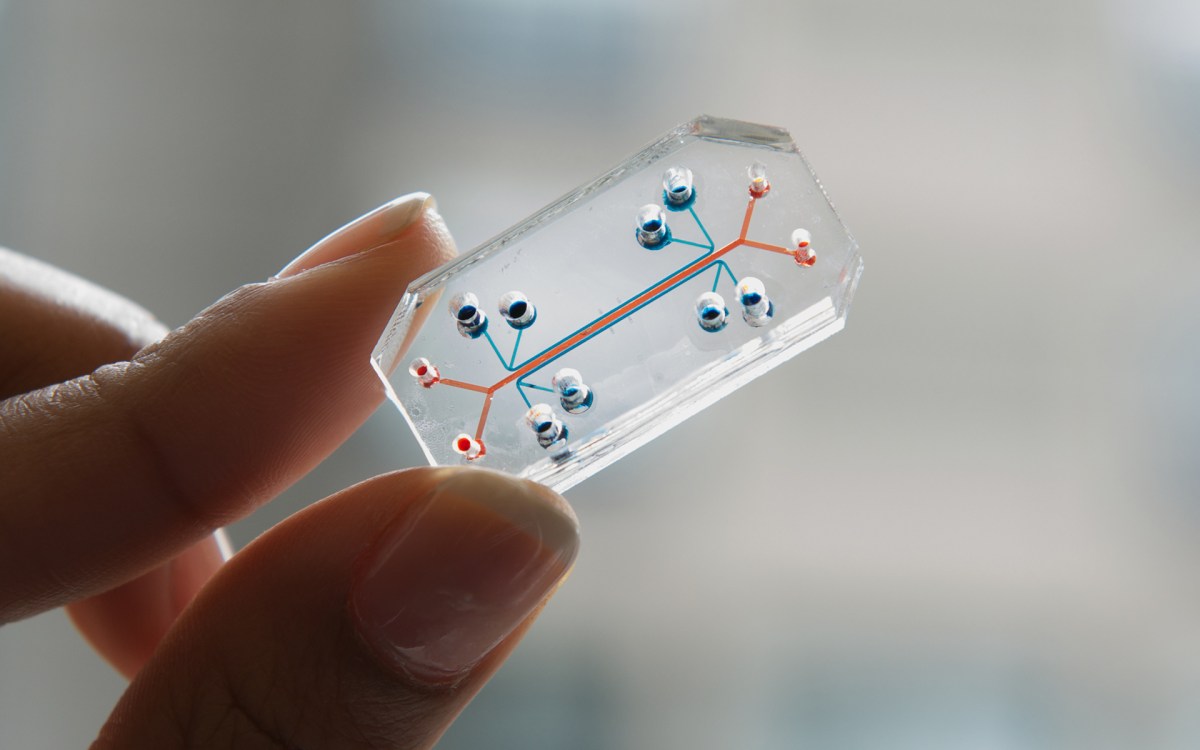

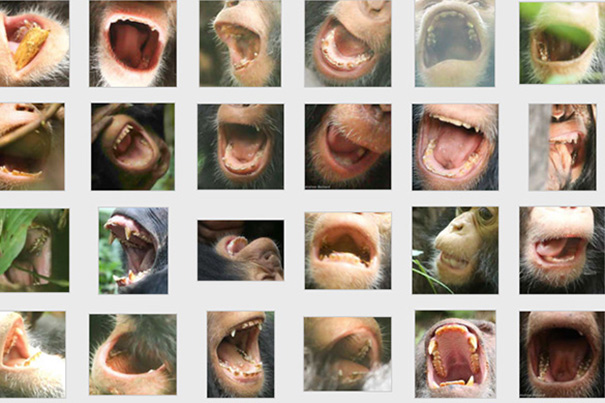

A sample of the hundreds of dental images collected during the 21-month photographic study.

Photo by Andrew Bernard

Watching teeth grow

Up-close research challenges connection between molar development, weaning in chimps

For more than two decades, scientists have relied on studies linking tooth development in juvenile primates with their weaning as a rough proxy for understanding similar landmarks in the evolution of early humans. New research from Harvard, however, challenges that thinking by showing that tooth development and weaning aren’t as closely related as previously thought.

A team of researchers led by three members of Harvard’s Department of Human Evolutionary Biology — professors Tanya Smith and Richard Wrangham and postdoctoral fellow Zarin Machanda — used high-resolution digital photographs of chimps in the wild to show that after the eruption of their first molar, many juvenile chimps continue to nurse as much as, if not more than, they had in the past. The study is described in a Jan. 28 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“When these earlier studies were published about 20 years ago, they found a very tight relationship between the eruption of the first molar and certain developmental milestones, particularly weaning,” Smith said. “A number of researchers have tried to extrapolate that relationship to the human fossil record, but it now appears that our closest living relative doesn’t fit that pattern. That suggests we should be more cautious if we want to infer what juvenile hominins were like.”

Understanding how those early human species developed, Machanda said, can help shed light on one of the most unusual aspects of humanity — childhood.

“One of the most important changes that occurred over human evolution is our extended period of juvenile development,” she said. “Compared to other primates, the apes have a very long childhood, and compared to other apes we have a very long childhood. By examining how chimps develop through their childhood, the hope is we can understand how and when that extended childhood began, and that will give us a greater understanding of the evolution of the human species.”

Getting an inside view of chimpanzee childhood, however, is no easy task.

Most prior studies of tooth development in juvenile chimps relied on observing captive animals or studying skeletal remains of wild primates. Both methods came with challenges for researchers.

Studies have shown that captive chimps grow dramatically faster — often reaching adult size by age 10 or 11, compared with 13 to 15 for wild chimps. That early development means the milestones researchers rely on as proxies for understanding early human species likely occur earlier than they normally would. Researchers studying skeletal remains of wild primates face another challenge. To properly understand those developmental landmarks, remains must be properly identified and aged, a notoriously difficult process for primates in dense tropical forests.

“This is a key species for us, because they are our closest living relative, so we need to make sure we’re getting the chimps right,” Smith said.

The researchers, studying the Kanyawara chimpanzee community in Kibale National Park in Uganda, teamed with wildlife photographers who snapped photos of the teeth of juvenile chimps whenever they opened their mouths.

“They are very well-habituated animals,” Machanda said. “We’ve been following them for the past 25 years, so they are used to human observation. But we don’t touch them, we stay at least five meters back from them, and we will not interact with them unless it’s absolutely necessary. The only time we would physically touch them is if they had some sort of injury that is life-threatening.”

The detailed photos, some of which captured the same individuals over months, allowed researchers to track precisely when molars erupted, and to closely correlate that information with behavior.

“In the past, these broad models have taken aggregate data from publications on tooth development, and aggregate data from behavior observations in the field, but no one had ever actually collected data on both this aspect of skeletal development and behavior development,” Smith said. “This new approach allows us to say when a tooth erupted, how long it took, and what was going on with that individual at that time. In one case we had images of an individual at 2.5 years old, 2.6 years old, 2.7 years old, and 2.75 years old, and you can clearly see the progression of the tooth — that’s what makes this so powerful for us.”

What the images revealed, Smith and Machanda said, came as a surprise.

Where earlier studies suggested that juvenile primates were weaned shortly after the first molar eruption, this study showed that, in addition to eating more solid food, chimps continued to “suckle as much, if not more, than they had before,” Smith said. “They were showing adultlike feeding patterns while continuing to suckle, which was unexpected.”

Researchers plan to follow up on the finding, Machanda said.

“We’re now working on a project that’s focused on body size and growth, but we’re also planning future studies that will look at their energetic condition so we can understand what they’re trying to get from the mother by continuing to nurse,” she said. “What’s interesting, however, is that there can be conflict surrounding this where the juveniles are trying to get as much as possible from the mother and the mother is actually covering up her nipples and moving around. Sometimes they’ll even throw these temper tantrums that look exactly like human babies.”

Said Smith: “I think there are two bottom lines here. One, I think, is a cautionary tale. The findings in this paper are going to challenge us to find other proxies for weaning and the spacing between offspring. But the other aspect that’s exciting is that we have some suggestion that we should start looking at how feeding behaviors develop in the wild.

“No one has looked at how infants become more adultlike, both in their food choice and in the time they spend feeding,” she continued. “This actually appears to correlate fairly well with dental development, so, while this is a preliminary finding, we may have a new anatomical proxy for when juvenile primates begin eating like adults.”

For more on the research, click here.