Over 25 days, using not much more than a team of Indian medical student volunteers and 10 iPads, the FXB team cataloged 40,000 patient records. Here, pilgrims gather for drug distribution at one of the pharmacies.

Photo by Kalpesh Bhatt

Tracking disease in a tent city

Public health researchers follow outbreaks in real time at India’s Kumbh Mela

This is the last in a series about Harvard’s interdisciplinary work at the Kumbh Mela, a religious gathering in India that every 12 years creates the world’s largest pop-up city.

ALLAHABAD, India — Ask to peek at a doctor’s notes or go behind the pharmacy counter in the United States, and you’ll likely be escorted out by security. Deepak Singh has a decidedly different attitude toward outsiders.

“Come in!” Singh said in his limited English, shuffling a group of Harvard doctors into his clinic, past the street-side folding table where one of his nurses was signing up patients. Singh, an Allahabad physician with a serious mien and a fuzzy pink sweater-vest, was eager to show off his 18-bed observation tent, his ambulance, and his stockpile of generic medications.

He had good reasons for such pride. After all, the clinic didn’t even exist four months ago, when the land it stood on was still covered in water. Back in the fall, Singh received a call from the planners of the Maha Kumbh Mela, India’s massive religious gathering held every 12 years, saying he would be needed to staff one of the festival’s dozens of hospitals and clinics, which would be built — like everything else in this temporary city — virtually overnight. By early January, clinics like Singh’s were up and running, ready to serve the millions of Hindu pilgrims who would be coming through to worship, as well a curious Harvard researcher or two.

“This is really impressive,” said Gregg Greenough, an emergency physician and assistant professor of global health and population at Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH), as he toured the clinic. “In my department, we only have 10 beds.”

Greenough found himself at the Kumbh as part of a research team run by Harvard’s FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, which planned to monitor all kinds of public health concerns at the Kumbh, from the provision of pre-hospital care (how quickly those new ambulances navigated the Kumbh’s crowded footbridges) to the management and care of lost children (a big problem in a crowd of millions speaking dozens of languages) to the quality of the drinking water and public toilets at the festival.

Managing disease, and resources

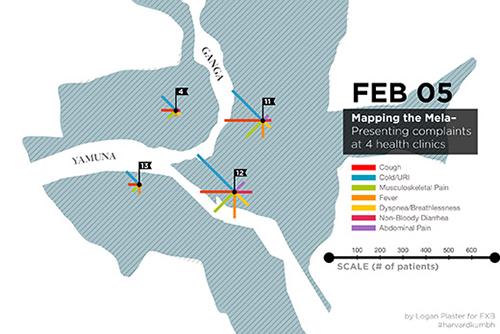

Greenough wasn’t there just to poke around in Singh’s records. He and his two colleagues, physician Pooja Agrawal and HSPH student Neil Murthy, were on a mission that day to secure permission from the Indian authorities to access medical records for the entire Kumbh, a 55-day affair in which 80 million pilgrims would pass through. The Harvard visitors’ ambitious plan was to track diseases spreading among four of the Kumbh’s 14 sectors in real time, tracing them back to their sources, and hopefully stopping their spread before large-scale damage could be done.

Measuring outbreaks “is a tough thing to do, because providers are busy providing care,” Greenough said. “They don’t always have an eye on diseases clustering in time and space.”

So Greenough and his colleagues did it for them. Over 25 days, using not much more than a team of Indian medical student volunteers and 10 iPads, the FXB team cataloged 40,000 patient records.

“Using that data, we’ve been able to generate daily reports for the field staff on the ground” and then given to Kumbh officials, said Satchit Balsari, an FXB fellow and a physician at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, who helped lead the Harvard team. “But we were also testing the proof of concept: Can you set up a system to track disease in this large-scale setting?”

Beyond monitoring disease, the Harvard team has also been able to look at how Indian officials utilized resources at the Kumbh. Take Singh’s clinic, for example. Most of the beds in the pristine facility, it turned out, were rarely used; in fact, all 18 cots were empty the day Greenough visited, their thin white sheets still crisply pressed. Meanwhile, the clinic’s staff was often overburdened with patients who had minor illnesses — often 500 or 600 a day, with only three nurses and one or two doctors on duty at a time.

In making such observations of how a large event plays out, the Harvard team hopes to help future planners of other mass gatherings better deploy the resources they have. That may be especially important at the Kumbh, where organizers plan well but lack the communication skills to respond to potentially tragic public-health disasters on the ground in real time. The stampede at a train station that occurred last month, killing 36, was a tragic reminder of how far the Kumbh has to go.

“In some ways, it’s bureaucracy at its best,” said Balsari. “It works as it’s supposed to work. But it doesn’t take advantage of new management tools, of new information. What you don’t have is a nimble feedback loop,” which is exactly what the Harvard team hoped to provide.

A role for educators

The massive amounts of data and dozens of public health lessons will also be used back at Harvard, where student interest in global health extends well beyond the confines of HSPH. The Harvard Global Health Institute (HGHI), a kind of University-wide think tank on health education across disciplines and one of two major funders of the project, along with the South Asia Institute, is planning a series of case studies based on Harvard research at the Kumbh. They’re hoping to create a permanent archive of research materials on the festival and its history, some of which they have already gathered in an online bibliography.

HGHI is interested in many forces that are shaping health worldwide, said its associate director of programs, Amanda Brewster — say, the effects of aging as humans live longer, or of globalization in a world where humans and their diseases are more interconnected than ever. The Kumbh project is HGHI’s biggest investment so far in studying the impact of urban development on the health of populations.

“This is a chance to think about some of the health challenges posed by rapid urbanization,” Brewster said. “It’s also an opportunity to look at health in these intersecting and unconventional ways.”

Getting down and dirty

The work of one group of students at the Kumbh would certainly be considered unconventional. Depending on your feelings toward outhouses, you could also call it brave, or gross. But the students — two HSPH master’s candidates and one Harvard College junior — simply called themselves “Team Toilet.”

They had traveled to the Kumbh with Richard Cash, a longtime senior lecturer on global health at HSPH who spends most of the year in India. Fifteen years ago, Cash organized public health trips to his adopted home country for Harvard students. Eventually, those January term outings morphed into a student-led “toilet mapping” project in Mumbai’s slums that have helped local citizens fight for better sanitation.

Given Cash and his students’ well-documented interest in managing human waste, a visit to the Kumbh seemed like a natural extension of their trip. His student researchers spent much of the week poking their heads into every kind of public toilet imaginable, from high-tech, plastic “eco-toilet” stalls to simple holes in the ground shielded by corrugated iron fencing. They also did their best to observe how pilgrims used the facilities.

“It sounds really weird, but we wanted to get user experience,” explained Leila Shayegan, the undergraduate who had willingly signed herself up for a week in the (sometimes literal) trenches. As Cash pointed out, public health isn’t just about what the government provides; it’s also about how people behave.

“That’s the thing you’ve got to observe: what people do, how do they do it, why do they do it,” Cash said one morning, as he watched a group of women huddle together next to a public toilet to urinate in the sand. “People don’t put aside their bodily functions so they can attend one of these festivals. … Students at Harvard mostly practice virtual public health in a classroom in Boston, but public health takes place in these environments, in situations like this where there are mass gatherings of people.”

Cash is something of a legend among HSPH students, including the two who were brave enough to follow him to the Kumbh’s muckier depths, Stephanie Cheng and Candace Brown.

“He basically invented oral rehydration salts,” Brown said to a newcomer to the group, as if someone had just professed ignorance of the Beatles. In the 1960s, Cash, a physician, and his colleagues conducted the first oral-rehydration therapy trials to try to combat potentially fatal dehydration in patients with cholera and other infectious diarrheal diseases. The treatment is now commonplace in the developing world.

“It’s crazy,” Cheng added, “but his work has probably saved millions of lives.”

You wouldn’t know all that if you stumbled upon Cash in one of the Kumbh’s several hospitals, where he was seated unobtrusively in the makeshift waiting room, wrapped tightly in a shawl in the local fashion.

“I’m not in a hurry,” Cash said, content to watch the action. When you deal in human waste, he deadpanned, “There’s no end to the fascination.”

His colleagues at the Kumbh — drawn to the messiness of public health in action, eager to learn from the festival’s successes and its failures — would no doubt agree.

Learn more about “Mapping the Kumbh Mela” and follow the South Asia Institute’s blog on the project here. Follow the FXB Center’s blog on the project, “Public Health at the Kumbh Mela,” here.

Read previous Gazette coverage of the Kumbh Mela here, and watch the Gazette throughout March for a series on Harvard’s work elsewhere in Asia.