Reshaping Manhattan’s Midtown

Design School alumni describe plan for new, taller buildings in long-developed area

The joy of teaching, according to Professor Jerold Kayden of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), “is seeing your students ripen into mature professionals who then make a real impact in the world.”

Nothing could better illustrate Kayden’s success in that goal than the role now being played by his former students in “one of the most major rezoning proposals that has occurred in New York City in years.”

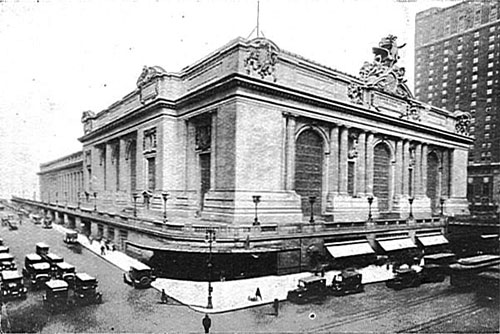

At issue is a proposal — certified Monday and moving quickly into the approval process — by the NYC Department of City Planning to revamp the 70-block area around Grand Central Station, where zoning restrictions have long restricted the height of buildings, to allow for structures twice as tall. The department says the increased density would allow the iconic neighborhood to retain its place as “a world-class business district and major job generator.”

The plan has come under fire from critics, including, in a spark of familiar Ivy rivalry, the dean of the Yale School of Architecture, Robert Stern, who wrote in a recent New York Times editorial that it “blindly [targets] what is oldest for replacement,” without “a broad look at what is worth saving. … The best path toward ensuring the future of East Midtown may well be that of preservation.”

Kayden called the plan “a high-stakes type of thing” that will leave its mark on the city for decades to come. “And Harvard alums are smack-dab in the middle of it,” he said.

On Wednesday, he gave his students a “frontline, minute-to-minute, blow-by-blow account” when he turned his class on public and private development over to two of the six GSD alumni who now hold important positions with the New York planning office: Edith Hsu-Chen, M.U.P. ’97, the director of the Manhattan office of the New York City Department of City Planning, and Frank Ruchala Jr., M.U.P. ’05, a city planner and urban designer.

Hsu-Chen told the packed classroom that the plan for East Midtown, a successful commercial center since Grand Central Station opened in 1913, will be a lasting legacy of Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration.

“This, many people would say, is the best business address in the world, and we want to keep it that way,” she said.

In addition to Grand Central, the area, in the center of Manhattan, hosts more than a dozen Fortune 500 companies, scores of financial and legal institutions mixed in with a sprinkling of digital and media companies and some nonprofits, as well as the landmark Waldorf Astoria hotel and St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

But the area faces serious long-term challenges to its continued ability to attract Class A tenants: aging building stock, limited new development, zoning impediments, pedestrian network bottlenecks, and competition from other cities.

Hsu-Chen said she and her team envision a strong and dynamic commercial district with most structures left unchanged, but with an improved pedestrian network; a small number of new, state-of-the-art, sustainable office towers; and increased density in some existing buildings. New buildings would account for only 4.5 million square feet of the additional 14.5 million square feet created by changed use, she said.

“The mix of old and new is part of the cachet of the area. We want to enhance that,” she said. “This is not a cannibalistic approach; this is a comprehensive approach.”

Ruchala said East Midtown has been “frozen in time for the last 20 years,” with zoning getting in the way of new developments. “People think of this as the main business address in America, and yet nothing’s changed in so long.”

He said the new plan would require developers to meet higher sustainability standards and contribute to a fund to make public infrastructure improvements. In addition, they would be encouraged to apply for “superior development special permits” that would allow increased floor-area ratios and transfers of unused capacity from a landmark building to a nearby parcel, in exchange for developed public space, enhancements to the pedestrian network, and contributions to the District Improvement Fund.

“We wanted the opportunity for people to come up with proposals for the next generation of iconic buildings” like the Chrysler Building, Lever House, and the Seagram Building, Ruchala said.

He seemed especially enthusiastic about the idea of turning Vanderbilt Avenue, alongside Grand Central, into an asset by turning it into a new, green, public space.

Hsu-Chen said the GSD’s focus matched well with the Bloomberg administration’s “holistic approach” to development, and Kayden, the Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design, said the School leaves its students uniquely prepared to address the challenges facing 21st-century cities.

“Our program has a special focus on the built environment and teaches students how to understand, analyze, and influence the variety of forces — economic, social, political, cultural, environmental, legal — shaping it. The built environment includes the buildings, the streets and sidewalks, the parks, all the things that together constitute what a city is,” he said.

“We believe and teach that if one does a better job shaping that built environment, that will ultimate help society as a whole.”