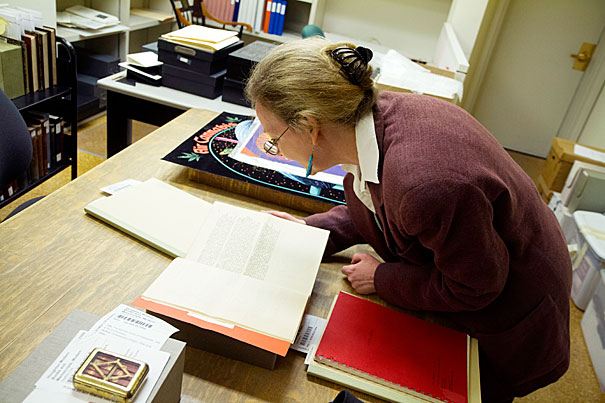

“We have been trying to acquire more in the way of what people generally refer to as popular culture material,” said Leslie Morris, Houghton’s curator of modern books and manuscripts and a longtime “Star Trek” fan. Harvard’s Houghton Library recently purchased a copy of “The Star Trek Guide,” an intriguing and often amusing handbook that includes everything that aspiring writers might need to know before crafting a script for the ‘60s cult sci-fi television series.

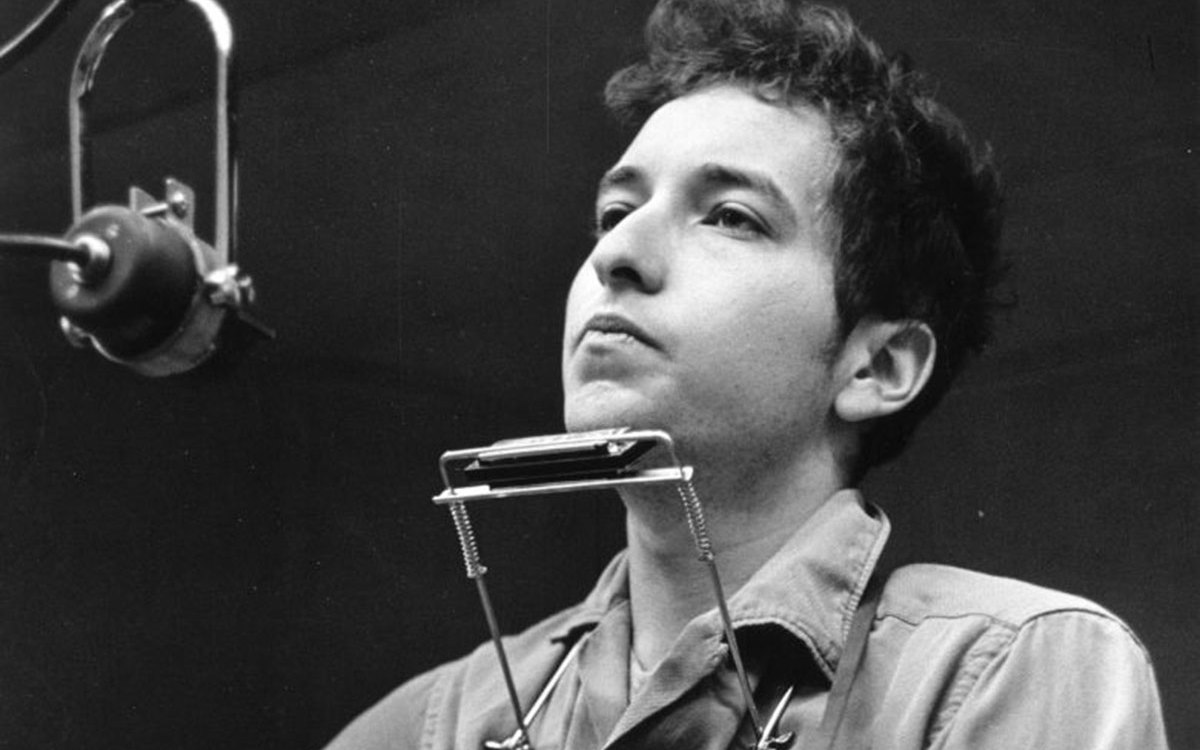

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Boldly going to Houghton

Expanding its pop culture holdings, library acquires detailed ‘Star Trek’ writers’ guide

The camera pans across the bridge of the U.S.S. Enterprise, where Capt. James T. Kirk and his crew are under attack by an alien vessel firing deadly bolts of photon energy-plasma. As the ship’s deflector shields weaken, Kirk turns to comfort and embrace a comely female yeoman as they await almost certain death.

Can you spot the fundamental flaw in this teaser? According to the authors of a guide for would-be scriptwriters of the original television series “Star Trek,” the scene involves a major format error for the science fiction fantasy. It is not believable.

“We’ve learned during a full season of making science fiction that believability of characters, their actions and reactions,” the guide states, “is our greatest need and is the most important angle factor.”

To test potential plot pitfalls, writers should always translate their ideas into “a real-life situation.” Using the previous example, the guide asks, if while patrolling Vietnam waters he was faced with a suicide attack from a boat carrying an atomic warhead, would Capt. E.L. Henderson — the then-commander of the navy cruiser the U.S.S. Detroit — turn to hug a pretty “female WAVE who happened to be on the bridge?”

“No, Captain Henderson wouldn’t! Not if he’s the kind of captain we hope is commanding any navy vessel of ours. Nor would Captain Kirk hug a female crewman in a moment of danger, not if he’s to remain believable.”

Harvard’s Houghton Library recently purchased a copy of “The Star Trek Guide,” an intriguing and often amusing handbook that includes everything that aspiring writers might need to know before crafting a script for the ’60s cult sci-fi television series that spawned several TV sequels, numerous films, countless pop cultural references, and even a complex internal language. The comprehensive manual includes details on the show’s ethos, characters, terminology, spaceship — even its snug-fitting uniforms.

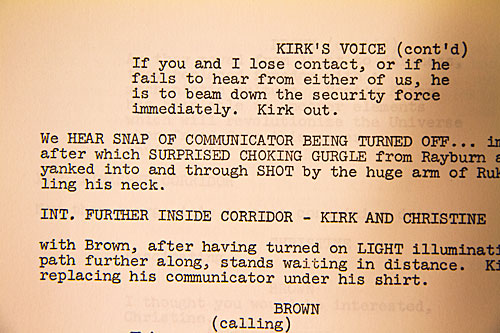

“Never have members of the crew putting things into pockets. There are no pockets. When equipment is needed, it is attached to special belts (as in the case of the communicator and the phaser),” reads the guide’s practical instructions.

The 31-page booklet, along with copies of four “Star Trek” scripts, is part of the library’s growing science fiction collection, which includes more than 3,000 volumes, largely 20th-century trade paperbacks, magazines, fanzines, and prozines.

“We have been trying to acquire more in the way of what people generally refer to as popular culture material,” said Leslie Morris, Houghton’s curator of modern books and manuscripts and a longtime “Star Trek” fan. (Her favorite episode is the show’s second season classic “The Trouble with Tribbles.”) While Houghton traditionally has been associated with early printed books and illuminated manuscripts and is more commonly known for its papers of literati such as Emily Dickinson and John Keats, there is growing interest from places like Harvard’s English, History, and Literature departments, said Morris, “in using more popular materials as well.” The guide, she added, “is part of that effort to bring material here that will support that kind of research.”

Morris suspects that the booklet, a third edition from 1967, is one of many sent to interested scriptwriters as a way for the show’s producers to weed out inappropriate material and “get more suitable submissions.” But in addition to being a writer’s how-to, the red-covered, mimeographed manual offers readers an in-depth look at one of the things that helped make “Star Trek” a cult sensation: its obsessive attention to detail.

The guide contains page after page of “Trekkie” gold. The Enterprise is “somewhat larger than a present day naval cruiser,” carries a crew of 430, and provides the TV audience a “familiar and comfortable counterpoint to the bizarre and unusual things we see during our episodes.” Of the ship’s engines, it says, “(the two outboard nacelles) use matter and anti-matter for propulsion, the annihilation of dual matter creating the fantastic power required to warp space and exceed the speed of light.” Warp speed, factor one, the guide notes, is the speed of light, or 186,000 miles per second. “Maximum safe speed is warp six. At warp eight, the vessel starts to show considerable strain.” Sensor, according the guide, is the ubiquitous term for any equipment used for “sensing” and “reading” a range of details, like the number of aliens on a ship, or the size of a meteoroid. “Never try to explain or describe the sensors, simply use them — they’re real because they are and they work.”

“Star Trek” first aired in September 1966 and was almost canceled during its second season because of poor ratings. But a massive letter-writing campaign by devoted fans gave it a lifeline and a third year on the air. Its last episode ran in June 1969. Many observers argue that the series’ initial appeal — and its wild success in reruns — came because the show touched on important issues of the times, including the space race and a burgeoning social revolution. Men would soon walk on the moon, and the Civil Rights Movement was thriving. A TV series that tracked the adventures of a spaceship patrolling unexplored parts of the galaxy struck a chord with viewers, as did the crew’s diversity. The crew, the booklet states, is “international in origin, completely multiracial.”

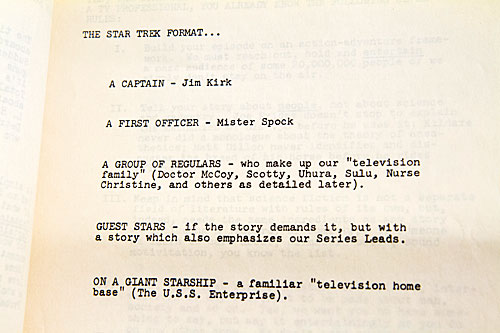

Lt. Uhura, the “quick and intelligent” communications officer, hails from the “United States of Africa” and is fond of singing during her off hours, both traditional songs and “space ballads.” She can also “do an impersonation at the drop of a communicator.” The ship’s helmsman, Lt. Sulu, is a compulsive hobbyist. One week he “may be fascinated by botany with the intention of that becoming his lifelong avocation, then another week we will find he has switched to a determination of acquiring a galaxy-famous collection of alien firearms.” Capt. Kirk is described as a “‘space-age Horatio Hornblower,’ constantly on trial with himself, a strong, complex personality.” Mr. Spock, the show’s famously logical human-Vulcan, has a “yellowish complexion” and “satanic pointed ears.” On his planet, any show of emotion, the guide notes, is considered “the grossest of sins.”

The manual also contains practical advice. The stories should always be “about people, not about science and gadgetry.” All scripts must have four acts, and run no longer than 65 pages. There are a limited of number of standing sets for the show, and “completely new and unusual sets are costly.” Writers should also “avoid long philosophical exchanges or tedious explanations of equipment,” and anyone in need of technical guidance should consider reaching out to a university, the aerospace research and development industry, or to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. But the manual also urges writers to ignore the fact that they are not scientists.

After all, it asks rhetorically, how many cowboys wrote westerns?

The latest in the “Star Trek” franchise continues with “Star Trek Into Darkness,” which opens nationwide on May 17.