“Freedom Rising,” a three-day conference in Boston and Cambridge, marked the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and celebrated African-American service in the Civil War. During a Harvard symposium on May 3, Professor John Stauffer (at podium) anchored a panel on the art and music of emancipation.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘Forever free,’ with caveats

Civil War scholars look at response to Emancipation Proclamation

Scholars from three continents gathered at Harvard recently to parse the Emancipation Proclamation, the earthshaking 1863 executive order from the Lincoln White House that proclaimed all slaves in the rebellious South “forever free.” It helped break the back of the Confederacy, gave the war its moral center, and rejuvenated federal forces starved for new regiments. (By the end of the war, about 180,000 black soldiers had served — 10 percent of the Union army.)

But for a century afterward, the proclamation also represented a historical irony: Until the 1960s, arguably, generations of American blacks were re-enslaved socially and economically by a recalcitrant South and a forgetful North.

On May 2-4, “Freedom Rising” expanded the celebration of this epic moment 150 years ago. It grappled with the facts of African-American service during the Civil War. It also explored the emotional antecedents of that service in what is now called the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804). (Led by Toussaint Louverture, that conflict created the hemisphere’s first black state. It also inspired a cascade of 19th-century slave rebellions.)

Among the sponsors of “Freedom Rising” were Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, and the National Park Service’s Boston African American National Historic Site.

Stars in the firmament of Civil War scholarship were drawn to the event. Eric Foner, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian from Columbia University, delivered “Lincoln, Emancipation, and African-American Soldiers,” the May 2 keynote address, at the Museum of African American History on Joy Street in Boston.

The African Meeting House there, built in 1806, was the site of the founding of the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832. By 1863, it was also the main recruiting site for the storied 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, which was among the first black units assembled during the Civil War.

On May 3, Yale University’s David Blight delivered remarks at a public symposium. Blight’s “Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory” (2001) is regarded as a classic study of the war’s aftermath — which included, he wrote, “the attempted erasure of emancipation from the national narrative.”

The symposium filled the Radcliffe Gymnasium nearly to capacity. Its points of focus: the impact of Lincoln’s proclamation on the rest of the world (dramatic) and the recruitment of black soldiers during the war (triumphal and — given the collapse of Reconstruction — poignant).

On the conference’s final day, actor Danny Glover participated in a pageant that was part of “Roots of Liberty: The Haitian Revolution and the American Civil War.” The setting was the Tremont Temple Baptist Church, where the proclamation was first read in Boston.

The spirit of the conference will live on in an exhibit, “Boston’s Crusade Against Slavery,” at Houghton Library through Aug. 23. It is the work of students in a two-semester course on Boston and emancipation, taught by John Stauffer, chair of the History of American Civilization Program.

Stauffer anchored a conference panel on the art and music of emancipation. Karen C.C. Dalton, editor of the Image of the Black in Western Art Research Project and Photo Archive at the Du Bois Institute, looked at three works that expressed the arc of the document itself, from hope for freed slaves, to despair, and back to hope again. A sentimental magazine illustration from 1863 showed the history of slavery. Its violent past ends with the centrality of a happy black household. By 1868, as shown in an illustration by Thomas Nast, a black soldier rests atop a monument, but behind him is a backdrop of violence; by then, Reconstruction was crumbling.

Then she showed an 1872 statute of a muscular and triumphant freed slave. It was made in Europe, where the joy of the proclamation still appealed to audiences. But in America by 1873, when the statue was displayed in Philadelphia, the triumphant freed man no longer embodied an appealing sentiment, said Dalton.

It took until 1897 for an artistic counterpart of that triumphal European image to appear in the United States, said Dalton: the dedication of the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial in Boston Common. The bronze relief sculpture celebrates the 54th Massachusetts, with Shaw on horseback leading a troop of black soldiers. Panelist and Duke University art historian Richard J. Powell called the work, by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, “an anomaly … a shimmering envoy from the fated past.”

The relief was radical in its day. It conveyed African-Americans as dignified, soldierly, and strong, in an era when representations of black Americans were starting to sink into the morass of minstrel-show blackface. Powell called the sculpture a “nondenominational American altar piece” that compressed into one work the “alchemy of moral imperative” in American race relations that had gone suddenly absent by 1897.

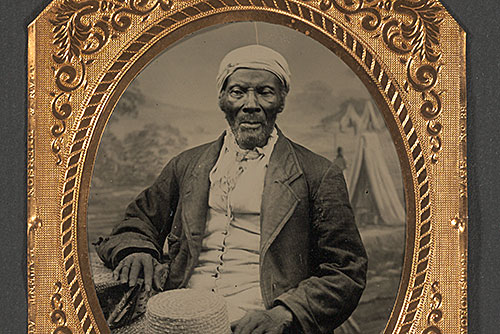

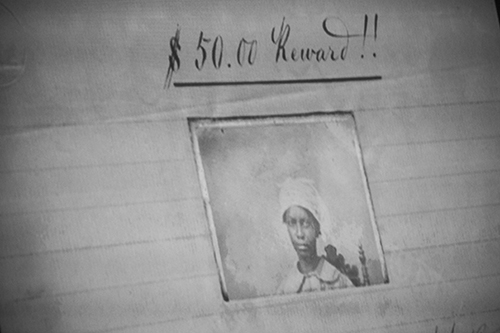

New York University’s Deborah Willis guided the audience through photography that represented blacks in time — and how such images, in the end, gave them a means to “self-emancipation” through dignified portrayals.

But first there were representations of American blacks as commodities. One showed a poster advertising a reward of $50 for Dolly, an escaped slave who was “rather good looking … with a fine set of teeth.”

Then came representations of violence, in images intended to make the case for abolition. One ex-slave modeled torture instruments; another showed his bare back, crisscrossed with silvery scars from the lash. Then there were images of triumph, as in a series of before-and-after pictures. One showed a black man in rags, and then in a smart Union army uniform. The images, said Willis, showed “the promise of emancipation through photographs.”

Stauffer ended the panel on a musical note, delivering a compressed version of his newest book, due in June: “The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song that Marches On.” It was a song whose easily memorized tune originated as a camp spiritual among black slaves; was revived as “John Brown’s Body,” a Union army marching song popularized by the 2nd Infantry Battalion of the Massachusetts Militia; and appeared again as Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” whose lyrics she wrote in November 1861. Her version was said to be Lincoln’s favorite song, said Stauffer — a tune that made him weep and, on one occasion, stand up and shout, “Sing it again!”

“Battle Hymn of the Republic” remained popular well beyond the Civil War, and took on the stature of a national anthem. By 1880, said Stauffer, even Southerners had embraced the song as a musical emblem of national reconciliation. It lived far into the future too, he said — “one of the legacies of the abolitionist movement.” Martin Luther King Jr. took it up as a freedom song during the Civil Rights Movement. That was an era, said Stauffer, that some scholars call “second Reconstruction.”

Blight, the specialist in how the Civil War is remembered, agreed that the Civil Rights era was a moment of triumph, and that it seemed to right the injustices of the century following the Emancipation Proclamation. But he added a warning, by way of a Ralph Ellison essay. “Even in our greatest moments of triumph … watch out. History is getting ready to come at us again.”