Mezzotint engraving of John Hancock, first published in England in 1775. Source: Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America

Photos courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Our signature 1776 revolutionary

John Hancock’s role as treasurer left an uneasy Harvard

John Hancock was an aristocratic Boston merchant, Harvard College graduate (Class of 1754), Revolutionary War hero, and the first patriot to sign the Declaration of Independence.

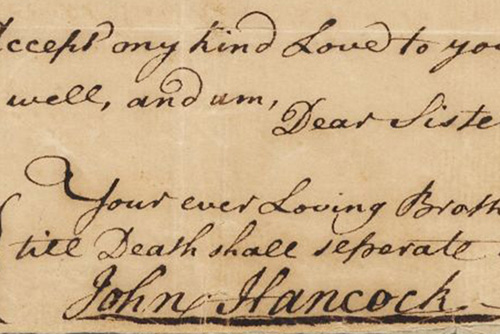

It is not Hancock’s patriotism, of course, that chiefly survives in the popular imagination 220 years after his death. It is his dramatic autograph — floridly large, and (in case we missed seeing it) underlined. The first synonym for “signature,” after all, is “John Hancock.” Harvard owns an early example, which anchors a signed 1754 letter to his sister Mary.

But as the Fourth of July approaches, it is useful to remember that around the time of the Revolution, Hancock — sequestered in Philadelphia and Baltimore with the Continental Congress — was wary of more than attacks from the hovering British. He was wary of attacks, by letter, from officials at Harvard College. They wanted their money back.

Hancock was elected Harvard treasurer in July 1773, taking into his possession 15,400 pounds sterling in securities, along with the College account books. By November 1774, Harvard President Samuel Langdon and others wrote the first in a two-year series of dunning letters to Hancock, calling for an accounting and for him to return the materials. The fifth such letter arrived at Hancock’s Concord, Mass., home in April 1775, a week before the opening battles of the Revolutionary War in Lexington and Concord. His response — the original resides at Harvard’s Houghton Library — was so chilly that he cast it in the third person, offering that “he very seriously resents” the letter’s implications.

On March 17, 1776, Langdon penned a more conciliatory letter, since by then he was fully aware of Hancock’s growing role in the unfolding Revolution.

One example of that growing centrality: On July 6, 1776, Hancock sent a freshly printed copy of the Declaration of Independence to Gen. Artemas Ward, a member of Harvard’s Class of 1748, who commanded Continental Army troops in Boston. (Harvard owns the original letter.) Hancock sent a similar missive to Gen. George Washington in New York. It contained the same message: Make sure everyone under your command hears about this.

Not long after, in November 1776, tutor Stephen Hall, an emissary from Harvard, confronted Hancock in Baltimore. (His expense report for the trip is in the Harvard University Archives.) Hall returned to Cambridge with the account books and other papers. By then, the Harvard-held bonds were worth 600 pounds more than they were when Hancock took possession of them, despite outlays for faculty pay.

This alternate personal combat, carried out in the shadows of the war that made a nation, became a story that dogged the Hancock legend far after his death in 1793. The man with the big signature became the man who had absconded with Harvard’s money. Historians soon stepped in to squelch this canard, and now it’s an incident barely remembered.

But in his own day, after the Revolutionary War, Hancock was still threatened with lawsuits from Harvard that claimed he still owed more than he had returned. But the claims were not public or credible enough that they affected Hancock’s blooming political career. (He became, for one, the first governor of the commonwealth of Massachusetts.) By the end of his first gubernatorial term, however, in 1785, Hancock did admit that he still owed Harvard a little over 1,000 pounds. But he was still stung enough by wartime accusations that he never paid up.

His heirs did pay up, including interest, in 1793. But an echo of Harvard claims survived into the 1940s. The allegation: Hancock’s estate still owed $526 in compound interest.

Back in 1773, before this 20-year row had erupted, it was easy to see why Hancock had been tapped as Harvard treasurer. For one, he was a celebrity among Boston merchants — a man who in 1764 had not only inherited an enormous fortune, but who was also known for tweaking royal colonial authorities by making money as a smuggler. In 1768, in an anti-tax prank that foreshadowed the American Revolution, Hancock smuggled a large cargo of madeira wine ashore from his aptly named company ship, Liberty. (You can’t make this stuff up.) The royal governor decided to make an example of Hancock’s defiance. He seized Liberty as its next cargo was being loaded, which set off a storm of anti-English protest. Overnight, Hancock became a sensation.

In some ways, the handsome Harvard graduate was an unlikely champion of liberty. He was the scion of a loyalist family who had turned from being a mild Whig to being openly a rebel. He favored silk brocade jackets and silver buckles, but the sartorial Hancock also had a common touch. He visited coffeehouses frequented by laborers and gave away free firewood to the poor.

Hancock’s story illuminates the real-life arguments that continued in parallel to the great events of the 1770s. (Not all great men of that era, his story seems to say, were busy with just great things.) It also allows for a glimpse at the Harvard College of Hancock’s youth.

The future Founding Father was 13 years old in July 1750 when he appeared at Harvard for his entrance examinations. They were oral exams, except for one required essay to be written in Latin. Hancock, taught at home for a longer time than most of his peers, had by then only been in school for five years. He passed and went on to enjoy the festivities. In those days, Commencement was also in July because the term referred to both seniors commencing life and to “sub-freshmen” like Hancock commencing their college careers.

As a freshman, Hancock sprang to the top of the list in class ranking, which was then determined by social status, not grades. It put him first in line at breakfast (coffee, chocolate, biscuits, and beer) and at the main meal of the day, at noon: one pound of meat and vegetables for each undergraduate, washed down with cider drunk from common vessels. (They were washed once a week. Plates were washed every few months.)

The future great man studied Greek, Latin, rhetoric, the Calvinist catechism, metaphysics, and all the other required courses. But he also likely indulged in the pastimes of those notoriously riotous days. The evening meal — usually a meat pie — was washed down with beer, a repast that more often led to more beer instead of more books. For extra fun, undergraduates in Hancock’s day would invite Titus — a local slave and Cambridge character — to their drinking parties. He would get drunk too. One historian estimated that Hancock’s late-18th-century Harvard was marked by greater per capita alcohol consumption than even the bathtub-gin era of the 1920s.

The same era at Harvard produced other Founding Fathers. They included Samuel Adams, John Adams, Elbridge Gerry (the fifth U.S. vice president, who lent his name to the practice of gerrymandering), and patriot and pamphleteer James Otis Jr. By chance, all of these Founding Fathers lived in Massachusetts Hall.

Other men in that august category had connections to Harvard.

Benjamin Franklin received an honorary A.M. degree in 1753, the first awarded to a nongraduate. George Washington received an honorary LL.D. in 1776, shortly after the fledgling Continental Army had harried the British army out of Boston. The degree, in Latin and translated in local newspapers, was signed by every member of the Harvard Corporation except Hancock, who was bottled up in war-threatened Philadelphia. It was Washington’s first academic degree. In 1787, Thomas Jefferson received an honorary LL.D.

In 1792, the year before his death, Hancock himself received the same honorary doctor of laws degree from Harvard — a sign that his troubles with Harvard had not gone very deep. Another sign came in October 1793, at Hancock’s mile-long funeral procession in Boston. Close to the front of the line were Harvard’s highest officials.