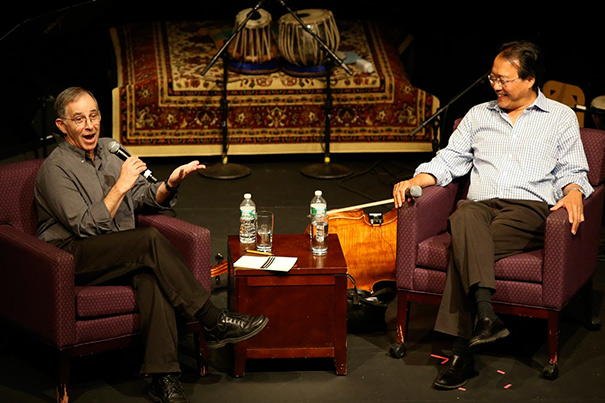

Harvard’s Steve Seidel (left) discussed education and the arts with cellist and Silk Road Project founder Yo-Yo Ma during the Wednesday kickoff of a three-day program called “The Arts and Passion-Driven Learning.” On Thursday morning, Seidel addressed 100 educators, asking them to “learn with and learn from each other” and be open to new approaches. The event was organized in collaboration with the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Silk Road Project.

Iman Rastegari/Harvard Graduate School of Education

Snakes on the brain

Using unusual example, HGSE’s Steven Seidel shows how blending arts with joyful learning breeds successful teaching

“We all live at the intersection of art and learning, and there’s always more to learn,” Steven Seidel told a group of educators at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) on Thursday.

Seidel, director of the Arts in Education masters program at HGSE, spoke in Askwith Hall about the lack of passion-driven learning in so many schools, and called for learning approaches that focus on joy, allowing students to be inspired and supported in their desires. “Nothing without joy,” a quote from the Italian educator Loris Malaguzzi (1920-94), is a guiding principle that Seidel would inscribe atop the school entrances.

There had been much joy on display the previous evening at the kickoff of the second annual professional development program for educators and artists presented by the Silk Road Project in collaboration with the HGSE. At the Farkas Hall event, Seidel engaged in a passion-driven discussion with renowned cellist and Silk Road Project founder Yo-Yo Ma about how the arts can enhance learning. The conversation was followed (or perhaps continued) with a crowd-delighting musical performance by the Silk Road Ensemble, under Ma’s artistic direction. Affiliated with Harvard, the Silk Road Project explores connections between the arts and academics. The ensemble has performed at many schools, supporting its goal of promoting arts and education.

On Thursday morning, Seidel asked 100 educators who came to HGSE for a three-day program called “The Arts and Passion-Driven Learning” to “learn with and learn from each other” and be open to new approaches. He asked the educators, the vast majority of whom were classroom teachers who’d come from many states and several countries, how they defined “passion-driven learning.” He cited answers they had offered in their program applications: One teacher defined it as “a strong emotional connection to the subject matter,” while others described it as “being inspired” and learning “based on an inner drive.” Seidel asked the audience to pair up and discuss how the arts could be used to engage students, make connections, build community, and work collaboratively.

After a few minutes of paired discussion, Seidel asked another question: “What is worth studying?” When he listed whales and the French Revolution, nearly every head nodded. When he cited snakes, there was some hesitation.

Seidel described the inspiring work of second-grade teacher Jenna Gampel, sitting near the front, who used a snake-centric curriculum to advance learning goals and engage students at the Conservatory Lab Charter School in Brighton.

Gampel defined clear learning objectives, explained Seidel, including helping students “make and record observations about snakes” and “draw scientific illustrations of snakes.” Seidel showed a slide of different drafts from one of Gampel’s students who carefully drew a detailed, lifelike drawing of an anaconda.

Gampel’s second-graders created an illustrated book called “What Snake Am I?” The book included text, drawings, and observations from students. Gampel also integrated literacy, noted Seidel, by exploring “how you take myths and misconceptions [about snakes] and get to another place” based on real information. Few animals have been so mythologized as snakes, Seidel added.

Gampel’s creatively engaged students went far beyond myth-busting, said Seidel. He showed a music video her students made with the help of a songwriter. Borrowing from pop sensation Lady Gaga’s hit song “Born This Way,” the second-graders created an anthem of snake acceptance, “Snakes Are Born This Way,” which the Askwith Hall audience watched in toe-tapping appreciation.

As one student sings in the video, snakes “are part of the world; don’t judge snakes by their looks.” The YouTube video combined dance, song, performance, fashion (with lots of kids wearing Lady Gaga-like large sunglasses), music, and, of course, knowledge about snakes. The pure joy of learning that Seidel had described earlier was displayed in abundance.

Seidel showed a second video, this of a songwriter engaged in the meticulous, back-and-forth collaboration with Gempel’s students to write the lyrics for “Snakes Are Born This Way.” Like so many creative collaborations, writing lyrics with enthusiastic young students seemed equal parts exasperation and exhilaration, as lines were suggested and then tossed out or embraced by the kids and the songwriter. Gampel’s students learned something about how music is built from the ground up through a painstaking, disciplined, but often joyful process.

As Seidel’s example showed, there’s lots of engagement, connection, community, and collaboration to be had by mixing the arts with even the unlikeliest of academic topics, such as herpetology. What’s needed, Seidel emphasized, is a more open-minded approach to integrating the arts into curricula.

Seidel closed by citing educator David Hawkins, who viewed academic disciplines as “a richly interconnected network of ideas … taken from many passages of experience.” Education should thus never be “a long march” ordered from above going in a single direction to some pre-determined place, said Seidel.

Better to have learners zigzagging across disciplines, following their passions and the need to connect, as when Gampel’s class learned about snakes, writing, music, dancing, and the creative process by making a music video about woefully underappreciated snakes.

The session was organized by HGSE’s Programs in Professional Education in collaboration with the Silk Road Project.