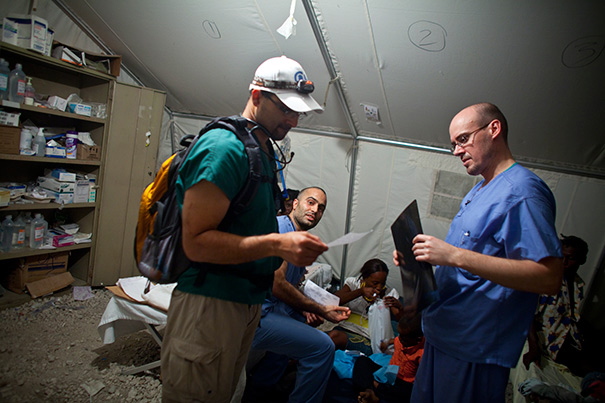

Harvard’s global presence continues to expand. In 2010, volunteers assisted in Haiti following the earthquake there (photo 1). In 2013, students and professors worked with scholars at the David Rockefeller Center’s office in São Paulo, Brazil (photo 2). Researching India’s Kumbh Mela and the “ephemeral city” was the focus across Harvard’s Schools in early 2013 (photo 3).

File photos by Harvard Staff Photographers; Kumbh Mela by Felipe Vera/GSD India Initiative

Citizen of the world

Harvard increasingly engages across nations, issues, peoples

This is the last of four reports echoing key themes of The Harvard Campaign, examining what the University is accomplishing in those areas.

Scholars who study the last financial crisis and others who probe climate change would not seem to have much in common, but their fields of study are characteristic of today’s pressing problems, which are often maddeningly complex and global in scope.

As humanity’s concerns go global, so too must the efforts to understand them. In recent years, Harvard has been strengthening its presence around the world, supporting international research, offering study-abroad opportunities, and opening offices in India, China, Mexico, Brazil, and other countries.

Technology has shrunk the world, increasing access to knowledge, facilitating communications, and fostering collaboration between researchers at different institutions who would expand that knowledge. And, as universities seek their place in a globalized world, nations with an eye toward accelerating economic development are putting money into higher education, creating fresh competition for the best and brightest faculty members and students.

Harvard President Drew Faust numbered the globalization of higher education among the top challenges facing Harvard in her year-opening speech on Sept. 10, and said during Saturday’s launch of The Harvard Campaign that meeting that challenge would be a fundraising priority.

“The future we face together will bring us closer than ever to people, ideas, and cultures around the globe,” Faust said at Sanders Theatre. “Harvard must bring the world to our campus and our students and faculty to the world. Harvard students and faculty must understand their lives and work within a global context, one enriched by the content of our curriculum, by a cosmopolitan campus, and by the opportunities available for significant international study, research, and engagement. Our campaign must strengthen the bonds between Harvard and the wider world.”

Harvard has long sought knowledge beyond national boundaries. Its museums and galleries are full of plants and animals, paintings and pottery, textiles and texts that hail from the far corners of the earth. Many of those collections date back decades and even centuries, as past generations of scholars worked to expand the University’s understanding of the world.

On campus today, a significant part of Harvard’s student body hails from abroad. Harvard’s International Office, founded in 1944 to help foreign students transition to life on campus, originally tallied just 240 students, a number that has grown since to 7,000 scholars.

Faust’s description of Harvard as a “cosmopolitan” place goes beyond the makeup of students and the countries they travel to and hail from. It also refers to the intellectual mix-in on campus. Here, students can study the history, culture, and language of societies around the world, with departments dedicated to the Near East, East Asia, Africa, and South Asia, as well as those centered on the Germanic, Romance, Slavic, and Celtic languages and literature.

Similarly, a variety of centers, institutes, and committees foster research into important global areas, including the Middle East, Japan, Asia, China, South Asia, Africa, Europe, Russia, Latin America, and Korea, among others.

“Across the University’s Schools, the expertise of the Harvard faculty spans the world,” said Vice Provost for International Affairs Jorge Dominguez. “In the social sciences and the humanities, there is impressive scholarly work about countries large and small, their politics and economics, their literature and art. Harvard shines its scholarly light on the academic study of countries and regions the world over.”

But the campus’ engagement with other people and cultures isn’t static, bound by the pages of books. It is a living exploration that is founded on past scholarship, but enriched and updated by new knowledge, including that imparted by a steady stream of campus visitors. Those range from political leaders — the president of Colombia and the prime minister of Norway are both speaking at the Harvard Kennedy School this week — to more offbeat visitors such as eL Seed, a Tunisian street artist who last year created some of his signature designs in Science Center Plaza.

This globally engaged community also is poised to respond when world events push scholarship into the background, using existing networks to reach out during disasters such as the 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami and the 2010 quakes in Haiti and Chile.

Over the past decade, Harvard administrators and faculty have wrestled with how Harvard can best help on global research problems, greater interconnectedness, and increasing demand for higher education. A study of the issue led by Harvard Business School Dean Nitin Nohria proposed that the University pursue a strategy of seeking the largest intellectual footprint with the smallest physical footprint.

What that means is the University has eschewed building campuses overseas, but has supported the efforts of programs and individuals to engage abroad. The President’s Innovation Fund for International Experiences, for example, awards grants to faculty members to assist with the difficult task of developing classes in other nations.

Instead of physical campuses, Harvard has opened supportive offices, some of which are dedicated to specific programs and Schools — Harvard Business School, for example, opened an Istanbul office this year — while others, such as the Harvard Center Shanghai and the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies’ offices in Chile, Brazil, and Mexico City, are intended as university-wide offices.

The issues explored by Harvard scholars abroad are perhaps even more varied than the places where they study them. Harvard researchers traveling the world often work with partners at local institutions to probe everything from the global sex trade to the nature of Anolis lizards on Caribbean islands, from the ugly, hidden side of the British Empire’s colonial rule to the devastating impact of diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria.

Earlier this year, for example, scholars from a variety of disciplines banded together to visit and analyze a massive but temporary phenomenon. India’s Kumbh Mela is a religious festival that occurs just once every 12 years and draws millions to the banks of the Ganges River. To house them, organizers construct a massive temporary city that is erected, lived in, and dismantled over the course of just weeks.

Scholars reached across disciplinary lines to create a research project there that investigated everything from religion to urban design to public health.

“We live in an era when knowledge is of growing importance in addressing the world’s most pressing problems, when technology promises both wondrous possibilities and profound dislocations, when global forces increasingly shape our lives and work, when traditional intellectual fields are shifting and converging, when public expectations and demands of higher education are intensifying,” Faust said in her year-opening speech. “I see many unprecedented opportunities in these developments — opportunities for our teaching, for our research, and for our global connections and reach.”