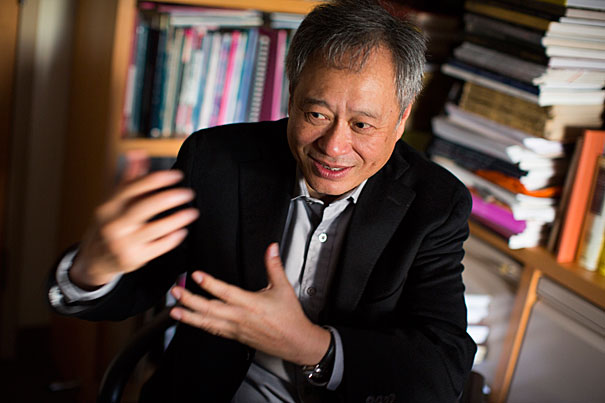

“I feel very fortunate I get to make these movies. I don’t create them, I participate in them,” said two-time Academy Award winner Ang Lee in a talk at the Sackler Museum that kicked off a weekend screening of his films at the Harvard Film Archive. “I am more like a vessel than a creator. … I love this … I also suffer for it,” he said. Lee was joined by his longtime collaborator James Schamus (photo 2, right).

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Life of Lee

Acclaimed filmmaker explains how he tackles tough topics to make compelling movies

Acclaimed filmmaker Ang Lee came to Harvard Friday and told a rapt crowd that the visit would have pleased his dad. “I think my father would be very happy,” Lee said during an afternoon of discussions and lectures that explored his far-reaching work. “I finally got into Harvard.”

The two-time Academy Award winner said his father, who was also his high school principal, disapproved of his early decision to go into filmmaking. Even after he won his first Oscar for best director for the 2005 film “Brokeback Mountain,” Lee said his father told him: “You’ve got an Oscar. You happy now? It’s time to do something for real.”

The hundreds of Lee fans who jammed the auditorium in the Harvard Art Museums’ Arthur M. Sackler Museum, along with millions more around the world, are no doubt glad the Taiwan-born film director, screenwriter, and producer stayed true to his artistic heart. Lee, whose most recent work was last year’s mesmerizing “Life of Pi,” is known for his wide range and complex themes, and his filmography takes on everything from comic books to cultural taboos.

“Wherever your gaze and your artistry land, I find a lot that is revealing and extraordinary,” said one admirer, Diana Sorensen, dean of arts and humanities and the James F. Rothenberg Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and of Comparative Literature, who offered opening remarks during an afternoon panel discussion and question-and-answer session with Lee organized in part by Harvard’s Fairbank Center for East Asian Research.

During the event, which preceded a weekend of screenings of Lee’s films at the Harvard Film Archive, Lee took the stage with his longtime collaborator, writing partner, and frequent producer James Schamus. The two met more than 20 years ago when Lee was searching for a producer for his first feature film, “Pushing Hands.” Schamus said that while Lee’s prolonged 45-minute pitch amounted to “one of the worst professional experiences I’ve ever had,” he also knew that the young director was someone special. “This guy was describing a movie; he wasn’t telling a story. … You could tell this was a filmmaker.”

Schamus signed on to the project and since then they have collaborated on 11 films, including “Brokeback Mountain,” “The Wedding Banquet,” “Hulk,” “The Ice Storm,” “Lust, Caution,” and “Taking Woodstock.” And though Schamus jokingly referred to himself as “VFSK,” his daughter’s nickname for him that stands for vaguely famous sidekick, it’s clear that Schamus is a vital part of the Lee system.

The two men said they relate to each other as trusted friends, philosophical sounding boards, and cultural barometers.

When wearing his writing hat, Schamus, who is also a professor at Columbia University’s School of Arts, said he pushes Lee to take chances and explore risky storylines. “To me it’s an extremely instrumental process, the writing process,” said Schamus. “It’s part of the filmmaking process.”

As a producer on a Lee film, Schamus takes on a more tactical role as “the guy who sets the table and tries to get the ingredients in front” of Lee. He also tries to make the film “as frictionless a human and mechanical machine as possible.”

Earlier in the afternoon, a number of speakers offered scholarly reflections on Lee’s work. Princeton Professor Jerome Silbergeld explored the director’s ability to tackle distinctly American stories with nuance, such as “The Ice Storm,” which chronicles two suburban American families trying to cope with the political and cultural changes of the 1970s, or the gripping Civil War drama “Ride with the Devil.”

“To study any artist, I think that you have to watch especially how either he or she responds to the particular potential of particular moments, as well as to the overall frame of the whole enterprise,” said Silbergeld, who called “Ride With the Devil,” “the most authentic and insightful of all the Civil War films I have ever seen.”

“Lee’s brave film,” Silbergeld added, “demonstrates that there were deeply held truths on both sides.”

During an interview after the talk, Lee attributed his ability to bring complex American stories to the big screen to growing up in Taiwan, and his years studying and working in the United States.

“I grew up worshiping America, watching American films, Hollywood movies, American television,” said Lee. “During the Cold War, we were living under the protection of America. And America is a country formed not by blood, by territory, by even culture. It’s by an idea, which is … unique in history. So we all looked up to America, growing up when I was young. Then, as you grow in America, you see there are other sides … I tend to get drawn into the materials that reveal a side of America I didn’t know.”

Throughout the afternoon, Lee’s sweeping martial arts and romance tale “Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon,” which has three sword-wielding women at the center of the action, generated plenty of discussion. Released in Chinese with English subtitles, the film became an international hit and nabbed the 2000 Academy Award for best foreign-language film. It also became the highest-grossing foreign-language film in American history, and the first Chinese-language film to be nominated for a best picture Academy Award.

“Why is there no sequel?” asked one member of the audience. “I believe [everyone] would love to see another movie in ‘Crouching Tiger’s’ magnitude and imagination and beauty.”

But Lee, who labored during the discussion and afterward in an interview to explain his deeply personal process and the connection he develops with each film, said he had tried for years to craft a prequel to “Crouching Tiger,” but finally had to let it go.

“Movies pass through my system,” he said.

In describing the genesis of “Crouching Tiger,” Lee said he “took something pulpy to show the subtext of a race of a nation, a group of people, a culture … sexual repression — just in case you didn’t notice the phallic symbol that the movie is fighting for” — a sword.

“When I am spending time with these movies, I am like Pi spending time with a tiger floating across the pacific,” Lee told the crowd during his introductory remarks. The director was referring to “Life of Pi” which tells the story of a boy stranded at sea and struggling to survive as he drifts, trapped in a lifeboat with a Bengal tiger.

“The only thing I know is I am with god, not as a religious god, the emotional connection to the unknown self, so to speak … I don’t know how to share that with you, but I will do my best.”

After the event, Lee expanded on that theme. Framed in a cinematographer’s perfect lighting, the muted glow of late afternoon sun shining through the window of a small office on the Sackler’s third floor, he tried to put his philosophy into words.

“I feel very fortunate I get to make these movies. I don’t create them, I participate in them,” he said. “I am more like a vessel than a creator. … I love this … I also suffer for it,” he said.

“I often think the movie theater is this black box, and that [it is] only through pretense that we actually get to touch the truth, that we can communicate with each other something we don’t use [words] to communicate because it would be too harsh,” he said. “I think that’s movies for me: It’s the discovery of ourselves and our relationships.”

Next, the director plans to bring the clashes between legendary boxers Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali to the big screen. The project would likely be an extension of his work on “Life of Pi,” and explore “man’s struggle with God and with himself.”

“One day, I read Joe Frazier died … and I thought: ‘How does this man deal with his God?’”

The symposium and film retrospective were sponsored by the CCK Foundation Inter-University Center for Sinology, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, the Harvard Film Archive, and the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, as well as Harvard University, in partnership with the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office.