Today, copies of the volume known as the “Bay Psalm Book” — translations from the Hebrew, and meant to be sung — are very rare, with only 11 remaining of the 1,700 printed in the first edition.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A literary treasure, unveiled

Harvard displays rare and valuable copy of 1640 ‘Bay Psalm Book’

The evening of Jan. 24, 1764, was blustery in Cambridge, with a light snow falling. Someone left a fire burning in the library fireplace at Harvard Hall, a two-story wooden structure then nearly 100 years old. Unattended, the flames soon spread and ate through the floor beams, set the building alight and burning it to the ground.

Destroyed along with Harvard’s scientific instruments were about 5,000 books. But 500 volumes out on loan or not yet shelved were saved.

The loss of the library was a disaster. In the 18th century, books were still expensive and rare. But following news of the fire, thousands of volumes poured into Harvard from benefactors. Among the donated texts was a first printing of the “The Whole Booke of Psalmes,” English America’s first book, published in 1640 on a printing press near Harvard that was imported from England in 1638, and was itself the first in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

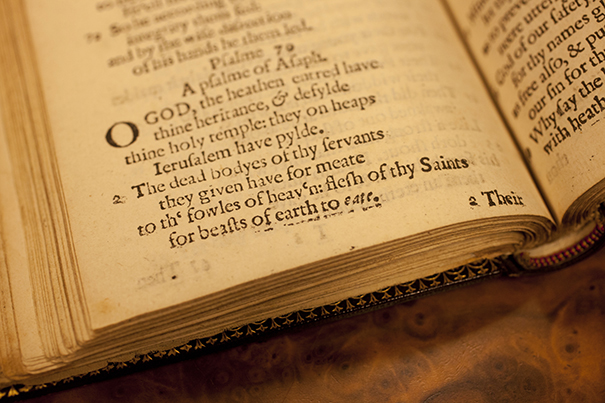

Today, copies of the volume known as the “Bay Psalm Book” — translations from the Hebrew, and meant to be sung — are very rare, with only 11 remaining of the 1,700 printed in the first edition. By comparison, there are something like 200 copies of Shakespeare’s First Folio and 49 copies of the 1455 Gutenberg Bible, which was the first book printed using moveable type.

The donor of the Harvard copy of the “Bay Psalm Book” in October 1764 was wealthy Boston landowner and merchant Middlecott Cooke, who had graduated from Harvard with an A.M. in 1723. The volume, mistitled as “Psalms in Metre,” appears on an 18th century inventory at the University Archives.

The Harvard copy — 7.1 inches high and bound in dark leather — is on display now through Dec. 14 at Houghton Library, where public hours run Mondays through Saturdays.

The timing of the display is no accident. The “Bay Psalm Book” has been in the news lately. A copy owned by the Old South Church in Boston will be auctioned off on Nov. 26 at Sotheby’s in New York. The sale, experts say, could fetch as much as $30 million.

“There’s been some heightened interest,” said the Houghton’s John H. Overholt, Curator of the Donald and Mary Hyde Collection of Dr. Samuel Johnson and of Early Modern Books and Manuscripts. Because of that, he added, the public will get to see a copy of the “Bay Psalm Book” from the same printing. Harvard’s copy was last on display in 1989.

“It’s got tremendous significance,” said Overholt. “It’s the first book printed in the future United States.” Meanwhile, “The financial value doesn’t really matter to us,” he said. “We’re never going to sell ours.”

If the Old South Church copy brings in $30 million, a cost comparison is in order. The last Gutenberg Bible sold in 1987 for $4.9 million, and it was an incomplete copy: just Volume 1, Genesis to Psalms.

The last complete (two-volume) Gutenberg to sell, in 1978, cost its buyer $2.2 million. Today, a complete copy — there are 21 — might command as much as $35 million. (One of the world’s complete copies is at Harvard’s Widener Library.)

The Gutenberg Bible is famously artful, with handsome type, generous margins, and rubrics (headings before each book) that were often colored in by hand after printing was complete.

The “Bay Psalm Book,” on the other hand, could be described as humble, even homely. Printed in a dimly lit shop on what is now Holyoke Street (Crooked Lane then), the run of 1,700 copies was marred by blurred type, missing words, inventive spellings, and typographical errors. At the base of some pages, lines bow upwards, where the press’ type was improperly locked in place.

Both the Harvard copy and the Old South Church copy, said Overholt, share an interesting mistake from the first print run: a few of the pages are in the wrong order.

Overseeing the printing job in 1640 job was Stephen Daye, who by 1655 would sign his name “Day.” (His boss was Elizabeth Glover, a widow who inherited the simple wooden press when her husband died on the voyage from England to the colonies.) Daye was a locksmith by trade, an ironworker by inclination, and barely literate. It is likely that his teenage son Matthew, who is believed to have apprenticed as a printer in England, brought what skill there was to New England’s first print shop.

Material challenges marked printing in Cambridge then. The type was worn, the press was sturdy but crude, the handmade paper was uneven, and the ink — a mix of lampblack and varnish — was poor. Everything had to be imported, including the paper.

An honest look at the “Bay Psalm Book” also reveals literary challenges. The translation was faithful to the original Hebrew, but the colony ministers at work were more scholarly than poetic. “God’s Altar needs not our pollishings,” warned the preface, and the translations within “have attended Conscience rather than Elegance.” The 23rd Psalm, for instance, begins this way:

The Lord to mee a shepheard is,

Want therefore shall not I,

Hee in the folds of tender-grasse,

Doth cause mee down to lie.

By the third edition, in 1651, the rude translation of the “Bay Psalm Book” was smoother, due in part to the scholarly Henry Dunster, Harvard’s first president.

But for all its faults, what we now call the book was a brilliant creation that rose above the technical limitations of the press and its early workers.

“There’s no experience like coming face-to-face with an important artifact from our history like that,” said Overholt, who hoped people would stream in to see the rare book under glass. “It’s what I do every day, and I’m still excited.”