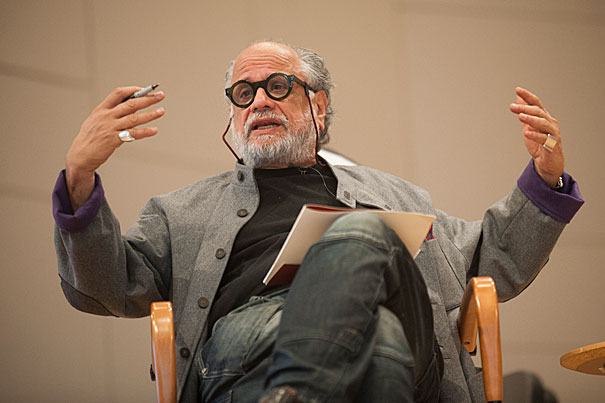

Homi K. Bhabha is at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris today representing the intellectual and academic world at the installation ceremony for Director-General Irina Bokova.

File photo by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

A Paris errand

Harvard professor addresses UNESCO

Harvard’s pre-eminent scholar of post-colonial literature, Homi K. Bhabha — born in India, educated in England, and a longtime professor in America — has traveled the world, including many stops in Paris. Bhabha is there today to represent the intellectual and academic world in front of an international body whose chief mission is peace through education and culture.

The United Nations Education, Cultural, and Scientific Organization (UNESCO) is hosting an installation ceremony for Director-General Irina Bokova. The 61-year-old native of Bulgaria was just elected to her second four-year term.

“She’s an extremely powerful but modest person,” said Bhabha, the Anne F. Rothenberg Professor of the Humanities, of Bokova, a onetime ambassador, foreign minister, and parliamentarian. “She’s a great listener,” he added, saying, “She does not sit easily with commonplace ideas.”

The installation ceremony is part of a UNESCO plenary session. On hand for Bhabha’s 10-minute speech, one of three for the evening, were representatives of the organization’s 195 member states, along with other luminaries.

Bokova is the first woman and the first Eastern European to be director-general. She is also a proponent of what she calls the “new humanism,” a set of universal values that acknowledges the world’s diversity and provides a framework for cultural cooperation.

The invitation to speak said new humanism was a thread running through Bokova’s first term, and will “constitute a major axis” during her second. “Cultural diversity for humanity is like biodiversity for nature,” she said in a brief acceptance speech following her Nov. 12 re-election. “Nowadays, it’s not sufficient to say we tolerate each other.”

Shortly after the 9/11 attacks, UNESCO enshrined its ideals of inclusion and acceptance in the Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Bokova’s new humanism is her own expression of those ideals.

New humanism is compatible with Bhabha’s longtime global campaign on behalf of the humanities, what he calls an integrative set of disciplines that provide an ethical framework in a world riven by cultural strife, a world in need of a way to communicate shared values. His speech, Bhabha told the Gazette before leaving, would describe new humanism as a means of negotiation at a time “when secular and religious beliefs are in a struggle with each other.”

Bokova has her own name for the balm that humanism could bring to the world stage: “software for peace.”

More than ever, “we need some way, some non-authoritarian way, to assert positive values across the world,” said Bhabha, who is also director of Harvard’s Mahindra Humanities Center. “We need to be able to invoke authority when we make decisions today.”

The humanities, after all, offer important ways to make “connections across systems of thought,” he said. That includes bridging the artificial divides that public discourse sometimes creates between art and literature and science and technology.

In the past, Bokova has made the same point about cultural connectivity. She likes to draw a parallel between health-giving diversity in nature and its counterpart in the world’s cultures. In his speech, Bhabha planned to use the same analogy: “Sustainability is often spoken of as an ecological issue, but it is no less an issue of our moral economy. Sustainability is as much a matter of the balance of social forces as it is a moral measure that regulates equitable outcomes in an uneven and unequal world.”

Bokova’s new humanism offers a way to progress in human affairs, Bhabha believes. But like any view of humanism, it acknowledges the contradictions of the human condition, the clash of aspiration with reality.

Today, the contradictions between humanism’s aspirations and its reality pile up around issues. Bhabha acknowledged the fruitful “connectivity” that global markets and technologies offer. But his speech also mentioned the counterpoints of economist Joseph Stiglitz and others, who warn that the International Monetary Fund and entities like it are sometimes viewed as new versions of colonialism.

These contradictions offer a lesson for the new humanism, Bhabha said in his speech, that it “can never be dogmatic or doctrinaire. Ideas that have a global significance must be open to global doubt.”

So healthy doubt — with its questions and its dearth of certitudes — underlies the new humanism. Bhabha calls it “an aspirational project,” not “a programmatic set of beliefs.” At the same time, it can be what Bhabha calls an “armature of action.” Bokova has said too that new humanism is policy, not philosophy.

Education could provide one example of that policy in action. The humanities are predicated on “inclusion and diversity,” Bhabha said, and education is served best by being the same way. Yet the global “map of knowledge” in the Internet age, he says, is “deeply distorted.” The Web is actually not so wide, according to Bhabha. It’s an information archive and retrieval system that has a Western bias.

On Wikipedia, for instance, 84 percent of articles relate to Europe and North America. At the same time, more articles appear there on Antarctica “than any country in Africa or South America,” he said, another sign of “educational un-sustainability.”

More support for the humanities could make up for gaps in the worldwide map of knowledge, Bhabha offered. But funding is a problem. One survey shows that U.S. expenditures for science and engineering are 46 times higher than for the humanities.

But Bhabha sees reason for hope, as Bokova does. With its mandate of cultural exchange as a means of peace, UNESCO is still aspirational. That’s OK, Bhabha says, because it remains “the ‘not yet’ that binds us to protecting and transforming the world as we know it.”