In all, Harvard lost 14 men during the Battle of Gettysburg. Eleven fought for the Union side — and three for the Confederates.

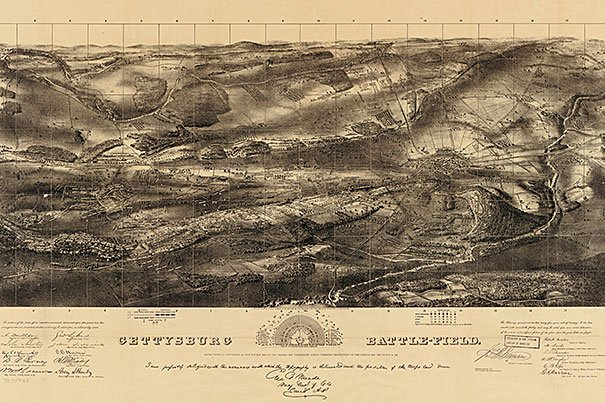

Courtesy of the LIbrary of Congress

Harvard in blue and gray

Toll at pivotal Battle of Gettysburg included 11 Union soldiers, but also three Confederates

One was reading a Dickens novel. One stood up to look around. Another was running across a meadow.

In the first three days of July 1863, in Gettysburg, Pa., death or a fatal wound could come at any time. And in great numbers: There were 51,000 casualties during the epic battle that marked the second and last and furthest penetration into the North by a Confederate army.

On the Union side, Gettysburg claimed more sons of Harvard than any other battle. In all, Harvard lost 14 men during the battle. Eleven fought for the Union side — and three for the Confederates.

In many cases, the Crimson dead, both blue and gray, fell during the same engagements. The events around and during Pickett’s Charge on July 3, for instance, claimed the lives of three Union soldiers from Harvard, and two Confederates.

First Lt. Henry Ropes, Class of 1862, was reading the Dickens novel in the quiet on the morning of July 3. About 60 yards behind him, on Cemetery Ridge, a federal artilleryman stuffed a defective shell into a cannon and touched it off. Shrapnel from the premature airburst knifed through Ropes, a popular officer with the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. He died on the spot, his last words being, “I am killed.” Ropes — who had boxed, rowed, and fenced at Harvard — was 24.

That afternoon, a Confederate force lined up three-quarters of a mile away and marched in a mile-wide formation toward the federal lines across a vast, upward-sloping field. This was Pickett’s Charge, into which the Confederates poured 12,500 men. By the end of the fighting, 9,000 had been killed, wounded, or captured.

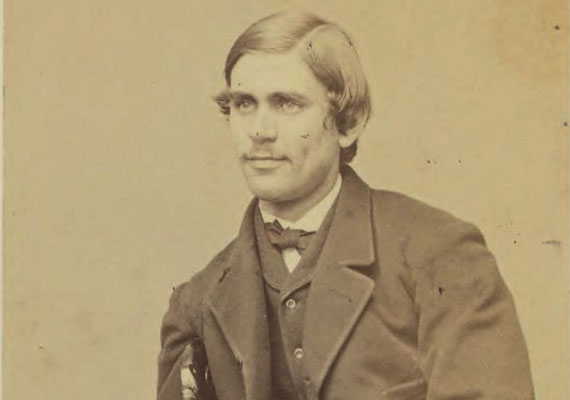

Sumner Paine, the youngest Harvard man to die in the war, fell during the last moments of Pickett’s Charge, when Confederate forces briefly broke through federal lines near a copse that still stands at the battlefield. A bullet cracked into one of Paine’s ankles, nearly severing the foot. He fell to one knee, waved his sword in the air, and was struck twice more. Like Ropes, Paine, who would have graduated in 1865, died where he fell. He had been in the war two months and one day.

On the other side during Pickett’s Charge was Capt. Elijah Graham Morrow of the 28th North Carolina Infantry. He was wounded and taken prisoner by the Union, had a limb amputated, and died on July 19. He was an 1856 graduate of Harvard’s Lawrence Scientific School.

Capt. Thomas Watson Cooper of the 11th North Carolina Infantry, an 1861 graduate of Harvard Law School, was killed on July 1. His unit was a microcosm of Gettysburg’s slaughter pen. Of 617 men with the 11th during the battle, half were killed, wounded, or went missing.

The Harvard deaths reflect the major facts of death and the Civil War, as outlined in “This Republic of Suffering” (2008), by Harvard President Drew Faust: the unequal match between modern arms and medieval tactics; the deaths from wounds that today could be healed; the lack of ambulance services; the ad-hoc aid stations; the hasty burials in crudely marked graves; the lingering romance of war despite the carnage; the power of class, and how that power diminished; the solace of Christianity on both sides; and — perhaps most surprising of all to the 21st-century mind — the presence soon after battle of family members on the field.

Harvard casualties

First Lt. Henry Ropes, Class of 1862, 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Died July 3, 1863. Courtesy of Harvard Law School Library

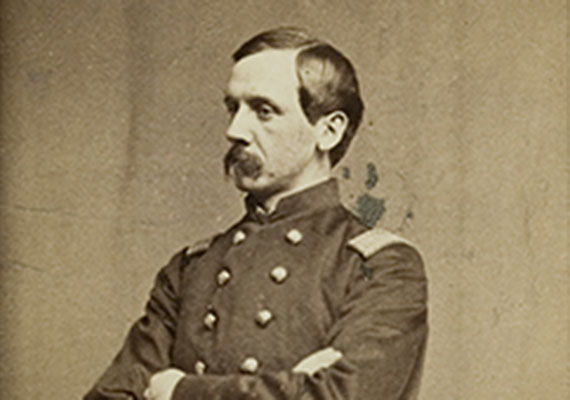

Col. Paul Joseph Revere, Class of 1852, 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Died July 4, 1863. Courtesy of the Special Collections, Fine Arts Library/Harvard College Library

Second Lt. Sumner Paine, Class of 1865, 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Died July 3, 1863. Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

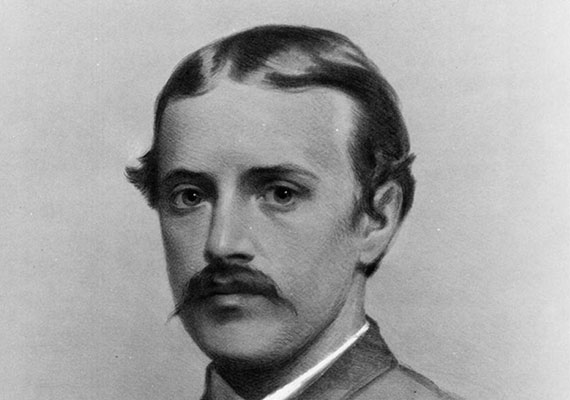

A drawing of 2nd Lt. Thomas Bayley Fox Jr., Class of 1860, 2nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Died July 25. Courtesy of Harvard University Portrait Collection

A coffin hard to get

The story of death in the Civil War is well represented in the tale of one man: 2nd Lt. Edward Stanley Abbot, who entered Harvard College in July 1860 and left in the spring of 1862 to join the Union’s 17th Infantry.

At Gettysburg, his unit was at the far left of the federal lines, at Little Round Top. Leading a charge there on July 2, Abbot was felled by a Minié ball that tore through his right lung and lodged near his spine. (Of 19 officers in his unit, 14 were killed or wounded.) Abbot was taken to an aid station five miles away. He lingered on a mat of straw under a hospital tent, and died on July 8. Abbot, who had once called the military “the only profession that rises above the commonplace,” was 21.

His brother, Boston lawyer Edwin H. Abbot, Class of 1855, traveled to Gettysburg soon after. It took him five days to find a coffin. When he finally stood at Stanley’s gravesite, he saw a shallow hole, barely covered over. It was marked with wooden boxboard, a battlefield commonplace. Within the grave, said the elder Abbot, his brother lay on a gray blanket, “in so natural a posture,” he wrote, “as I had seen him lie a hundred times in his sleep.”

Abbot’s battlefield grave was a mark of class: He had one. (Graves were often denied, at least right away, to enlisted personnel.) His brother’s visit, and the coffin, was a mark of class too, one most often reserved for officers. But the gravesite also represented the war’s breaking of class boundaries. Standing next to the older brother were two soldiers from a sister unit. “He was a strict officer, but all the men liked him,” said the younger soldier. “He was always kind to them,” Edwin Abbot wrote later. “That was his funeral sermon.”

Other family members raced south to see their wounded sons. Sgt. John Lyman Fenton of the 9th Massachusetts Battery was one of two enlisted men from Harvard who fell at Gettysburg. He was wounded July 2 and died in a Baltimore hospital on July 28, just hours after his mother and his wife of four months arrived. He had entered Harvard in 1857 at age 22, but left after three terms for financial reasons.

Sgt. Edward Chapin, who would have finished in the Class of 1864, left Harvard after two years for different reasons: an eagerness for war that propelled him to sign on as a private with the 15th Massachusetts Volunteers.

He was wounded on July 2 but remained on the field unseen until July 5. One ball had hit his right knee; a second struck the same spot; and a ball of case shot had churned into his hip.

In an illustration of the slow ambulance services, Chapin did not arrive at a hospital until July 7. But he was recovering when another commonplace of the Civil War took his life on Aug. 1: sepsis and fever from his lingering wounds. Chapin’s funeral, at his grandfather’s house in Whitinsville, Mass., illustrated another common thread of the war, the heavy toll often taken on one family. The grandfather buried three grandsons.

Scenes of courage

Heroism and death are often linked. At Gettysburg, courage wore both blue and gray.

On July 2, Col. Strong Vincent, Class of 1859, climbed to the top of a boulder at Little Round Top. Ten feet above his men from the 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry, he waved a riding crop and shouted, “Don’t give an inch!” A moment later, a bullet cut through his left thigh and into his abdomen. He died from his wounds five days later.

On the same day, Col. Paul Joseph Revere, Class of 1852 and commander of the 20th Massachusetts, spent the late afternoon walking through the ranks. Confederate shot and shell rained in on the federal lines, the center of which was occupied by the 20th. Around 6 p.m. this grandson of the famed Revolutionary War patriot stood to look around. Overhead, a shell exploded, sending a ball through Revere’s lungs and into his abdomen. He died on the Fourth of July.

On July 3, at the foot of Culp’s Hill, Confederate troops had captured Union breastworks tucked inside a line of woods. Across a wide expanse called Spangler’s Meadow, Lt. Col. Charles Redington Mudge of the 2nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and the Class of 1860 received an order to attack. “Well, it’s murder,” he said of the command to charge over exposed ground, “but it’s the order. Up men, over the works!” In the middle of the meadow, Mudge was struck in the throat and fell dead.

Second Lt. Thomas Bayley Fox Jr., Class of 1860, fell wounded in that same 400-yard charge, a 20-minute action that cost the 2nd Massachusetts 134 of its 294 men. Fox, who never packed his battle kit without including works by his beloved Horace and Shakespeare, died on July 25.

Second Lt. Thomas Rodman Robeson, Class of 1861, also with the 2nd Massachusetts, was part of a line of skirmishers far in front of the main force on July 3. They were concealed by stones and logs in an open field near the Confederates who were in the line of woods. Robeson joined the main attack and was struck by a ball that shattered the bone in his upper right thigh. He died July 6.

Robeson gave proof of the fatalism of many Civil War soldiers at the prospect of death — an attitude that in most cases came with the added comfort that heaven was the next stop. Robeson, a descendant of Puritan separatist Roger Williams, was told in the hospital he would not live long. “Well, I suppose I must go,” he said.

The same day, the 20th Massachusetts illustrated the same tragic math of battle: Of the 200-plus members of the 20th Massachusetts who entered the fight, only three officers and 20 enlisted men were left standing at the end.

Fighting on the Confederate side was Brig. Gen. Albert Gallatin Jenkins of the 8th Virginia Cavalry. He was wounded in action during the battle, but recovered, only to be killed on May 21,1864, at Cloyd’s Mountain, Va. Jenkins was a 1850 graduate of Harvard Law School and a onetime representative in both the U.S. and the First Confederate congresses. He was also a bold cavalryman who was known for his northern raids into both Pennsylvania and Ohio, a state in which he was supposedly the first to unfold the stars and bars of the Confederate flag.

Gettysburg today

Today, the landscape around Gettysburg, much of it rendered sacred ground as a military park, looks the same as it did 150 years ago: low rolling farmland, jutting hills rounded with thick woods, and everywhere ancient boulders scattered over the terrain by a receding glacier. The coloration of the place has a 19th-century look: sere browns, muted greens. Gettysburg is still rendered in sepia.

A 10-minute walk from the visitor’s center takes you through undulant thick woods tangled with underbrush and thick with boulders and rocky outcrops. It is frankly spooky, a reminder of a historic place we first experience in old photographs of the dead, strewn on fields or propped against rocks.

The landscape is a reminder that the Battle of Gettysburg was a slaughterhouse set in lush farmland rich with crops. There are battle sites named after plums, roses, peaches, and wheat. It was at the Wheatfield — 20 acres of high grain — where more than 20,000 men grappled in battle on July 2, often hand-to-hand. The casualty rate was 30 percent.

It was likely there that Lt. Col. Henry Macon Dunwoody of the 51st Georgia Volunteer Infantry died. He was a homeopathic physician who had graduated from Harvard Law School in 1847.

That short walk from the visitor’s center opens out onto hilly, bare land. You pass the headquarters of Union Gen. George Gordon Meade, a white clapboard farmhouse so narrow and low that three of them could fit end to end in the atrium of Harvard’s Smith Center.

Two hundred yards northwest of the farmhouse, up a steep rise to Cemetery Ridge, is the rectangle of land held so fiercely on July 2 and 3 by the 20th Massachusetts, which was called the “Harvard regiment” because that’s where most of its officers originated. The plot is perhaps 50 yards wide, marked by granite tablets, and 75 yards deep. It was the killing field for Ropes, Paine, Revere, and 28 others from the 20th.

To the left, two miles distant, you can see Little Round Top, where Vincent and Abbot were fatally wounded. A short distance to the right is the copse that marked the Confederates penetration into Union lines in the aftermath of Pickett’s Charge, the “high-water mark,” historians say, of the Confederacy. A wrought-iron fence encircles the copse’s seven surviving trees, bent and bare.

The plot of ground at Cemetery Ridge, held by the 20th for two days, is about the size of set Harvard Yard. For two days in 1863, you might say, it was.