Haunted by the siege

70 years later, Leningrad survivors tell their stories through words and images as part of ‘Blokadnitsy Project’

One winter day during the Siege of Leningrad — an 872-day World War II blockade that left more than a million civilians dead — a Russian nurse came across the body of a small boy. He sat at the curb, frozen solid, one hand in his mouth.

“I realized he died of hunger, trying to eat his fingers.”

Testimony like this — wrenching, frank, and often flat-toned — is part of “The Blokadnitsy Project,” an exhibit of work by fine arts photographer Jill Bough now on view at Harvard. (“Blokadnitsy” are women who survived the siege.)

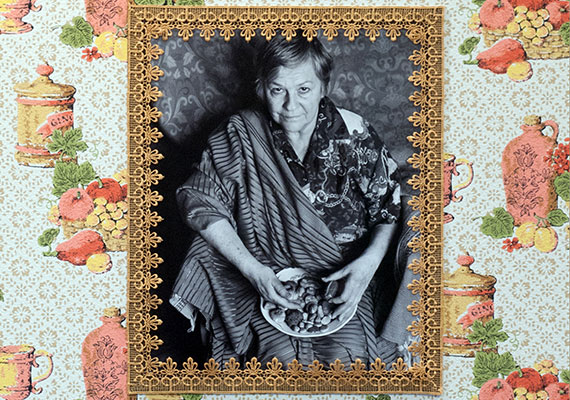

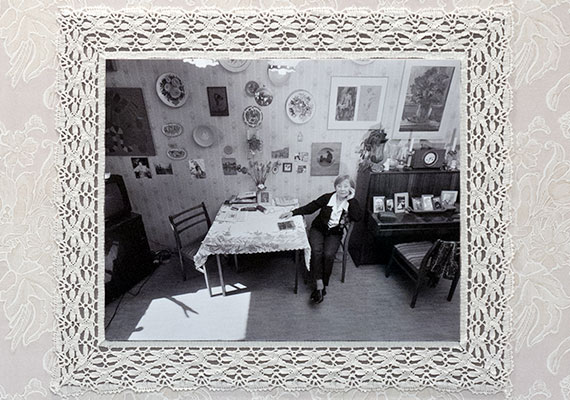

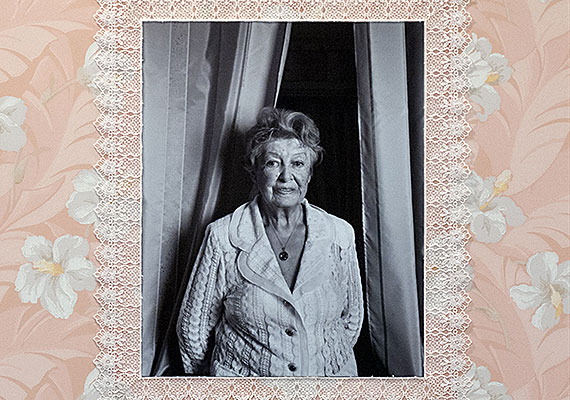

The images on display are artistically complex: black-and-whites of 12 survivors, framed with collages of artifacts from their apartments, lace or big-flowered wallpaper. Beneath each photo is a handmade album consisting of old photos, new photos by Bough, and newspaper clippings. Personal testimony is rendered in the photographer’s clear print.

‘The Blokadnitsy Project’

Lyubov: “We tried never to separate. We had a rule in our family; die together.” Details from photographs by Jill Bough

Galina: “We, the survivors, are bonded by a strange fate. There is even a name for us. Blokadnitsy.”

Nadya: “Adults would help me draw water, but no one would help me carry it home. People were not being cruel. They were surviving.”

Bough wanted viewers to experience the lives of these women at an intimate distance, one that was tactile, full, and personal; a portrait alone makes a viewer step back, she said.

The nurse is called “Nadezhda,” a nom de guerre of a sort — just as the other 11 names were invented for the exhibit, eight years in the making. The women, in their 80s and 90s, were not just shy talking to an American, but reluctant to talk to anyone who had not seen the siege, Bough said. They had seldom mentioned the war even to their families, and guarded their privacy as they once did their own lives.

“We saw everything,” said Galya. Today, she meets once a week with fellow survivors in a choir to rehearse old war songs.

Alla remembered the cold of 1941-1942 in a few words. “That was the winter mother and I turned bald.”

Luda was part of a city crew that looked for bodies. Burials took place after winter, often in mass graves excavated with explosives. “We stacked dead bodies like firewood,” she said. Bough took a close-up in Luda’s neat apartment. “These are the hands,” said Luda, “that performed this nightmare.”

For one picture, Emma showed a small samovar that survived the siege with her, along with a cracked-face doll patched with tape. “Like everyone else during the siege,” she said, “we burned our entire library to stay warm.”

Trauma and loss are reflected in the ways the women live today. “They are hoarders,” said Bough of her subjects, who are still wounded by the deprivation they both felt and witnessed.

The apartments themselves were oblique reflections of trauma — deliberately cheerful, as a rule, with full pantries, full shelves of books, and walls full of mementos. Nadya showed a picture of her father. He died — the family thought — fighting Germans at the front. “My whole life,” she said, “I have been waiting for his knock on my door.” Nadya is 84.

There was another “constant theme” among the group, said Bough. The apartments were full of trinkets and maps and items related to travel — yet none of the women had ever ventured outside Russian borders. They all wanted to, but foreign travel was not easy in the Soviet era, for one. And they seemed fearful outside the ken of their tiny dwellings.

Harvard is the first stop for “The Blokadnitsy Project,” sponsored by the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies. Bough will next take it to Bozeman, Mont., her hometown. But — still careful of her subjects’ privacy — she will not take it to St. Petersburg, the city that from 1924 to 1991 was called Leningrad. “They have no concept of how public things are these days,” said Bough. The survivors agreed on the idea of the show, and in the end wanted to tell their stories — but “I need to protect the women from their personal trauma,” she said.

Why just women survivors? Bough offered several reasons, including their comparative number, since men 55 and younger were at the front, and their camaraderie — many women with memories of Leningrad have banded into clubs. (Galena called her friends from the era “my girls.”) Also, the photographer has an interest in Russian women that goes beyond the project. The exhibit, on the concourse level of the CGIS South Building through Dec. 16, includes selections from other shows: “Russian Women I Admire” and “The Russian Heart: Scenes from a Village.”

The Siege of Leningrad blurred gender lines. Women built fortifications, worked in factories, kept fire watch, learned the ABCs of machine gunning, and — of course — dug graves. Then there was the blurring of how everyone looked. Luda described it this way: “People all looked the same: thin and bald.”

The survivors illustrate other, deeper costs. Ludmilla is one example. “I believe all people who survived the war are the same,” she told Bough, in perhaps the exhibit’s harshest moment. “They have no sympathy for others.”