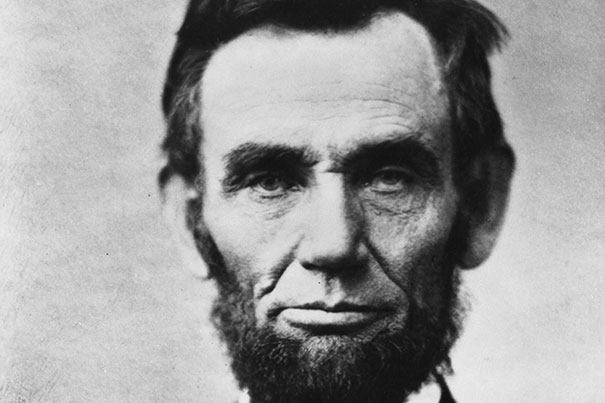

A detail from a famous photograph of President Abraham Lincoln. It was taken by Alexander Gardner on Nov. 8, 1863, just weeks before Lincoln would deliver the Gettysburg Address.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Words to remember

Harvard experts reflect on meaning of the Gettysburg Address, 150 years on

Everyone knows about the Gettysburg Address, which turns 150 years old this month. They know it was President Abraham Lincoln’s signature speech, delivered at the site of the signature battle of the Civil War, one that turned back the highest Confederate tide as it rose violently into the North.

But not everyone knows Harvard’s connection to the fight or the famous address. Harvard lost 11 of its sons because of the battle: three died in the field, all on July 3, and eight others died soon after, when they succumbed to wounds.

Soundbytes: A reading of the Gettysburg Address

Sumner Paine is the sole Harvard officer from the 20th Massachusetts buried at Gettysburg, Pa. He had left Harvard in his sophomore year to join the army and died three months later at age 18 on a rolling field that became a graveyard during Pickett’s Charge, the Confederates’ ill-fated, bloody assault on the Union lines that many analysts agree effectively ended the battle and forced General Robert E. Lee to retreat with his army back into the South, to Virginia.

As he took his last breaths, Paine reportedly said, “Isn’t this glorious?”

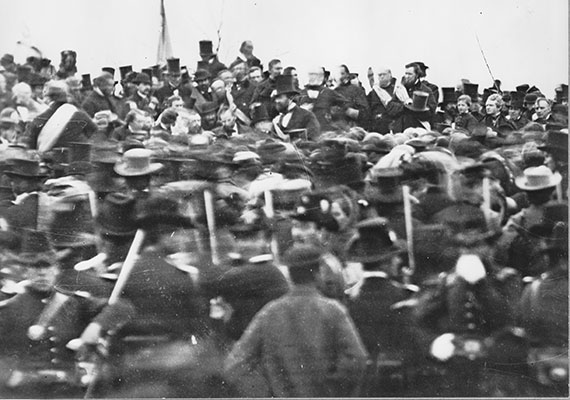

Four months later, approximately 15,000 people gathered on the battlefield for the dedication of the first national cemetery. Bodies still lay covered by thin layers of dirt, the smell of death still hung in the air.

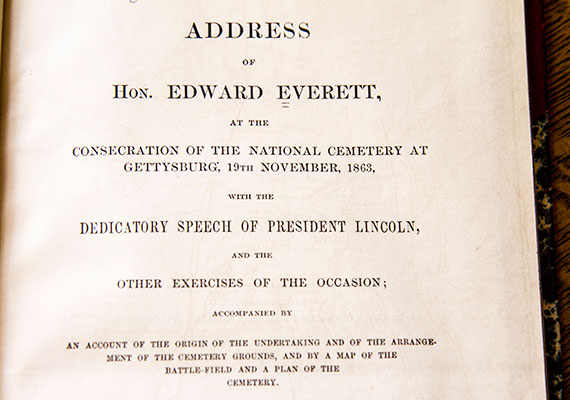

Former Harvard President Edward Everett was the main speaker on the dais that day. Lincoln’s remarks were considered something of a footnote, a short dedication near the end of the ceremony. Renowned for his oratory, Everett delivered a two-hour address, a sweeping, 13,000-word account of the history of the battle, peppered with comparisons to the wars of antiquity. Lincoln, in his high voice and strong Midwestern accent, delivered a brief talk in which the word “Gettysburg” was never uttered.

Like their speeches, the two men were different. Lincoln was an awkward, self-taught country lawyer from Kentucky. Everett was a Harvard-educated minister’s son who studied and traveled in Europe and became a professor of Greek literature at Harvard, and later its president.

But the Gettysburg speech that became woven into the country’s cultural fabric was Lincoln’s. He delivered just over 270 words in two minutes, and in the process helped a broken nation begin to heal.

In the run-up to the 150th anniversary of that famous address on Nov. 19, five Harvard scholars offered their views on its history, language, and legacy.

Harvard President Drew Faust, a Civil War scholar, said that the speech, like the battle, represented a turning point for the country. Historian John Stauffer reflected on how the address captured a fractured political climate. Political philosopher Meira Levinson called the address a “teaching tool” still robust after 15 decades. Shakespeare scholar Marjorie Garber pointed out echoes of the Bard in the text. And the Rev. Jonathan Walton proclaimed the speech one of the most “prophetic statements in American history.”

Faust: Words that marked a crossroads

Faust, whose seminal book “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War” explores how the country coped with the conflict’s unprecedented fatalities, said that Lincoln’s words that day marked a critical crossroads for a grieving nation. With his speech, the president linked the sacrifice of those on the battlefield to a higher cause, offering the living, including those in mourning, a sense of purpose and meaning.

“It ties a cost already paid with something that then must be delivered on, ” she said. “We’ve paid for our freedom, now we have to make sure we claim it.”

“If you’ve lost someone and you feel that the world is a better place in some way because of that, that’s consoling,” Faust added. “This is a statement of purpose for a nation. It’s also a statement of consolation for the people of a nation.”

Stauffer: A reflection of a moment

For John Stauffer, professor of English and African and African-American studies, the ambiguity of the speech — Lincoln did not explicitly mention slavery or emancipation — was a reflection of the moment in which it was given, as well as a cause of its enduring popularity in the North and, perhaps more surprisingly, in the former Confederate states.

“He gives this speech in a moment when he thinks he is going to lose re-election,” said Stauffer, author of nearly a dozen books set in the Civil War era.

The address endures in large part because of its beauty. “It’s a brilliant, lyrical speech,” said Stauffer, adding that the organizers’ request for “brief” remarks from the president encouraged Lincoln to cast his words “at the loftiest, most lyrical level that he could.”

Despite the Union victory — on Northern soil — at Gettysburg, the U.S. military effort appeared to be flagging after more than three years of long and, for the Northern electorate, unexpectedly brutal warfare. To Lincoln’s great disappointment, Union armies in the East had failed to capitalize on Gettysburg’s military success.

Meanwhile, conservative Democrats in the North — whom their critics derisively called Copperheads, or snakes — were increasingly challenging Lincoln’s war policies, including the rising profile of emancipation as a war aim, with many arguing instead for an immediate cessation of hostilities. With the presidential election of 1864 approaching, Northern Democrats hoped to use the war’s growing unpopularity to turn Lincoln out of office.

As a result, Stauffer argues, Lincoln was extremely measured in his Gettysburg remarks, avoiding detailed predictions about the war or its policies, instead opting for soaring rhetoric that might appeal more broadly to audiences, including those in the seceded states.

“He’s very uncertain about the future, which I think is part of the brilliance of the speech,” said Stauffer. “He’s proscriptive in encouraging soldiers to dedicate themselves to be willing to sacrifice themselves to honor the dead who are already there. But he doesn’t say we are going to win this war; he doesn’t say that victory is assured.”

Walton: A sense of “humility and sobriety”

Lincoln was well aware what he was asking of those soldiers. The staggering death toll weighed heavily on him, and he regularly visited wounded troops to comfort them.

Walton, Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church and Plummer Professor of Christian Morals, said Lincoln’s sense of “humility and sobriety” about the devastating cost of the war comes through in his words.

“He’s not beating his chest here. He’s not a champion of the cause of the Union, but rather, it’s through their noble sacrifice that this nation can begin to become what so many believe God had ordained for this nation.”

Garber: Moments of breath, moments of emphasis

While some people adhere to the notion that Lincoln quickly scribbled down the address en route to the ceremony, scholars agree that the man known for crafting carefully thought-out legal arguments worked on the speech in Washington before he left for Gettysburg, and continued to tinker with it after he arrived.

Lincoln usually worked tirelessly to perfect his prose. In his book “Lincoln at Gettysburg,” author Garry Wills wrote that Lincoln “would have agreed with Mark Twain that the difference between the right word and the nearly right one is that between the lightning and a lightning bug.”

The autodidact relied on his knowledge of classical tradition to model his address after Greek funeral orations, and called on his knowledge of the Bible and the Bard to help him refine and perfect his message.

“He knew his Shakespeare extraordinarily well and quoted from it, echoed it,” said Garber, the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of English and of Visual and Environmental Studies, “the cadences, the sense of repetition, the moments of pausing.” She added, “This is why it can be performed so well by amateurs as well as actors, because the moments of breath and the moments of emphasis and so forth are written into the language in a way that is very Shakespearean.”

Levinson: Myriad themes that can be fruitful

Associate Professor of Education Meira Levinson said that while Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” a defense of nonviolent resistance penned in 1963, and his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech delivered a few months later are the more standard texts in civics classes today, the Gettysburg Address remains a touchstone work in many classrooms.

Lincoln’s speech and its myriad themes of reconciliation, national identity, the demands of war and peace, honor, and sacrifice “can be incredibly fruitful and important when working with kids,” said Levinson, who is also co-founder of the Civic and Moral Education Initiative at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Many educators still teach the address. Over the summer as part of a three-week theater project, members of Harvard’s American Repertory Theater worked with local high school students to develop a performance piece inspired by the Gettysburg Address and the Emancipation Proclamation.

The speech figures prominently in the Common Core State Standards Initiative, a set of shared educational benchmarks for English and math that have been adopted in more than 40 states. As part of the English standards, a comprehensive, three-day module guides students through a close reading of the address. Students translate sections of the speech into their own words, and examine the meanings behind Lincoln’s arguments.

Levinson concluded that Lincoln’s famous speech “in fact, is probably being taught more this year in classrooms across the United States than it has been in decades.”

Yet the address, as profound as it remains today, does contain a clear error: “The world will little note nor long remember what we say here.” As the continuing discussion shows, Americans will remember.

Making history

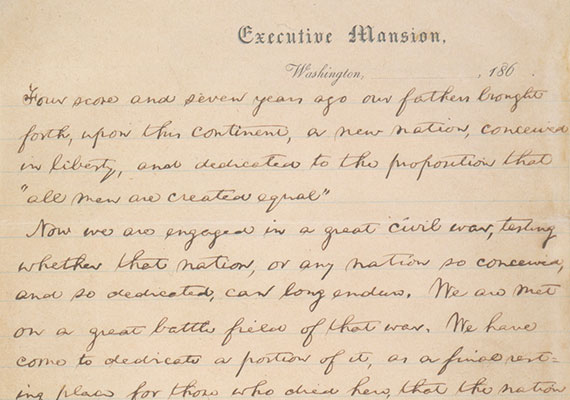

Of the five known manuscript copies of the Gettysburg Address, the Library of Congress has two. President Lincoln gave one of these to each of his two private secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay. This is called the “Nicolay Copy.”

A detail from a map of Gettysburg that includes the battlefield and hospitals. Both “Union and Rebel Hospitals” are represented. Image from the Andover-Harvard Theological Library. Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

President Abraham Lincoln standing on a platform at the dedication of Gettysburg, Nov. 19, 1863. This is a facsimile from a glass-plate negative. Courtesy of the Brady-Handy Collection/Library of Congress

Edward Everett, a former Harvard president, was the main speaker at the dedication. His speech lasted two hours. Image from the Andover-Harvard Theological Library. Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer