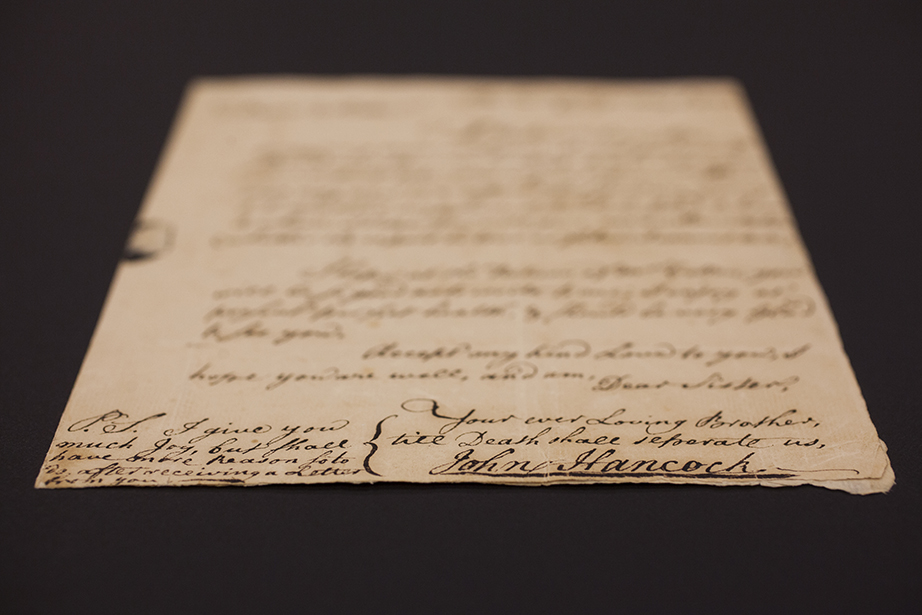

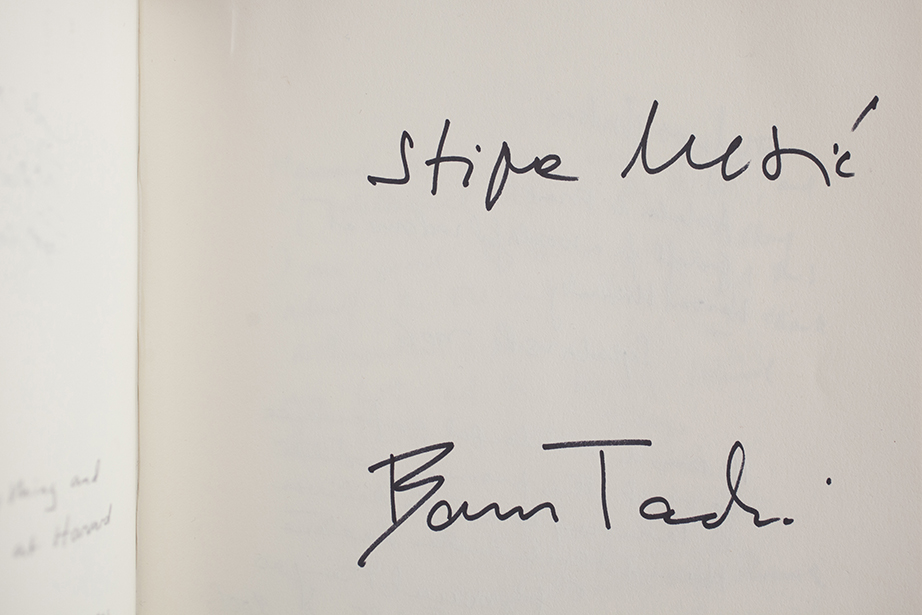

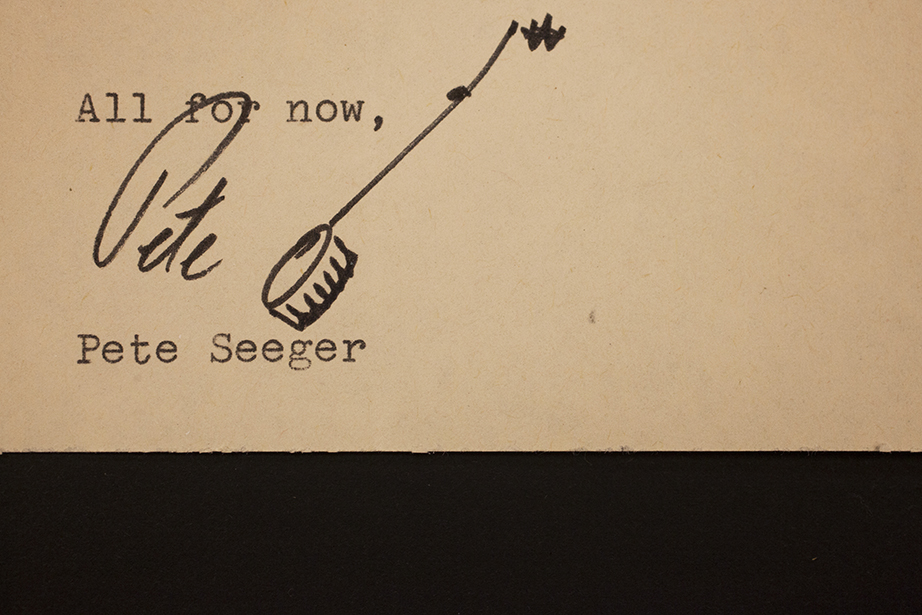

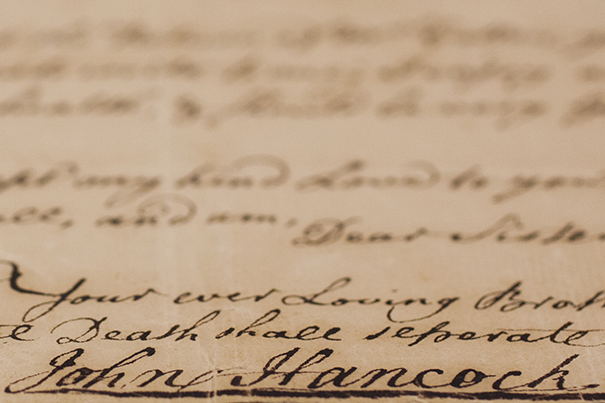

A signature by John Hancock is pictured from the collections at Harvard Archives at Harvard University. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Signature signatures

Harvard’s archives, guest albums contain signatures of the great, the known, the revered

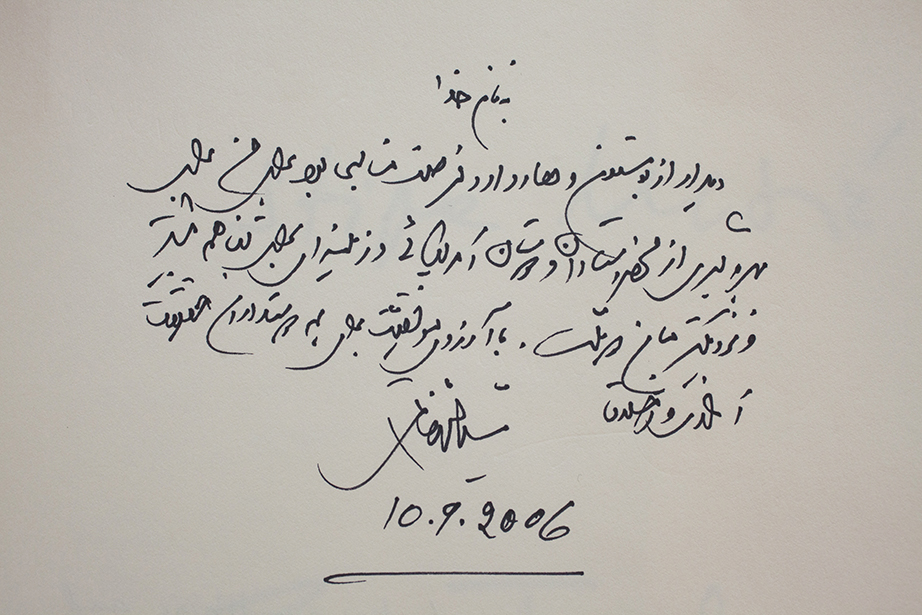

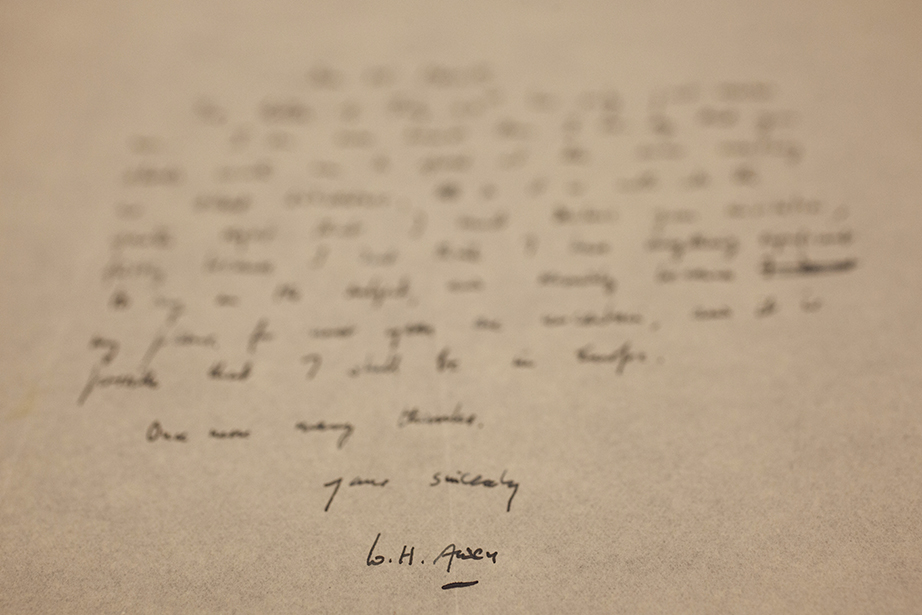

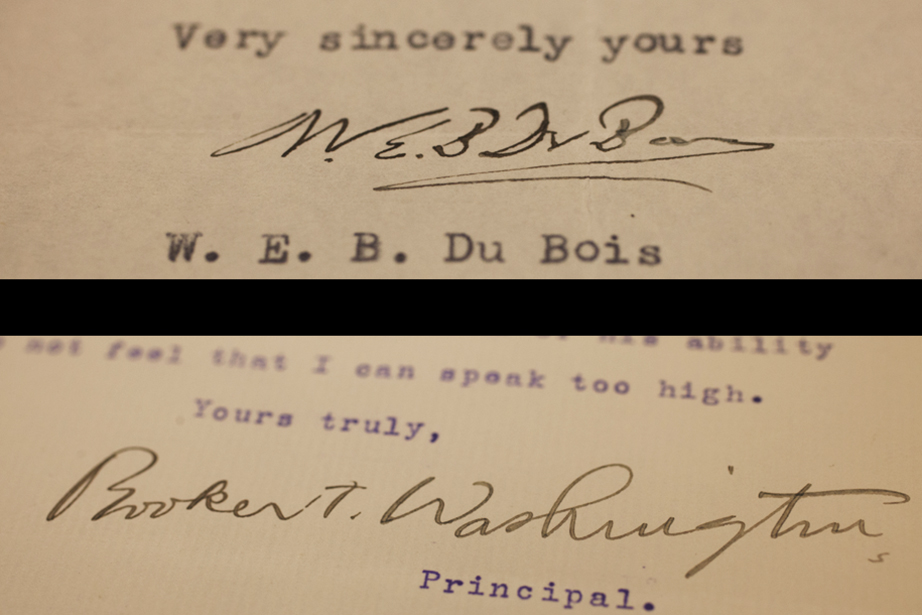

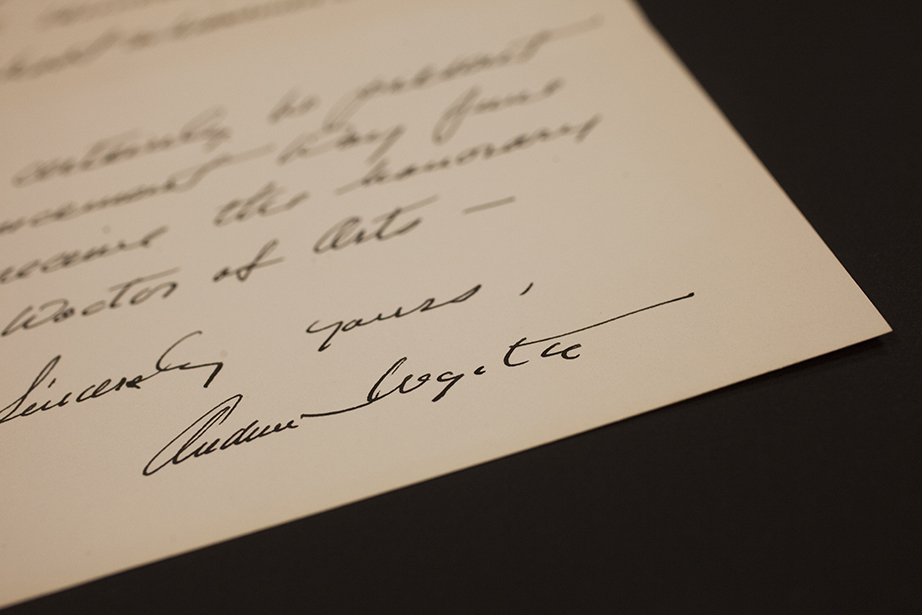

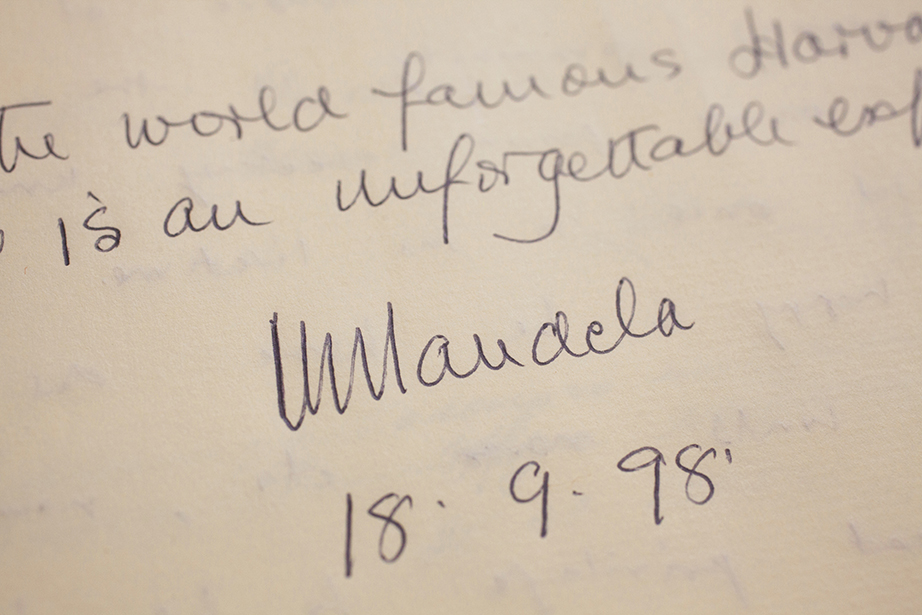

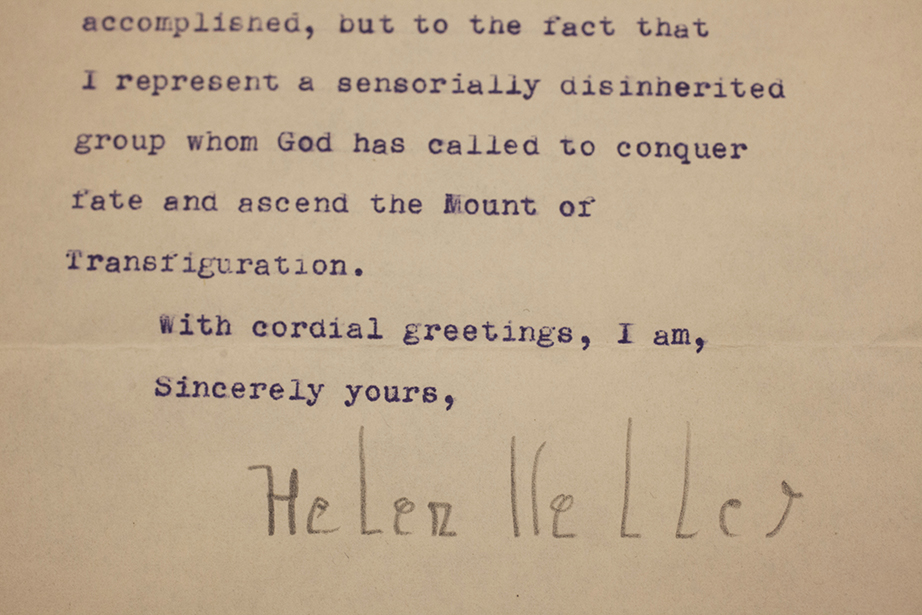

They loop and swoop and dip and dive. They jitter and circle and march in straight lines. Some are small, and some tall. Some are humble, others grand. These are the signatures of Harvard: the handwritten names of the famous who have visited the University.

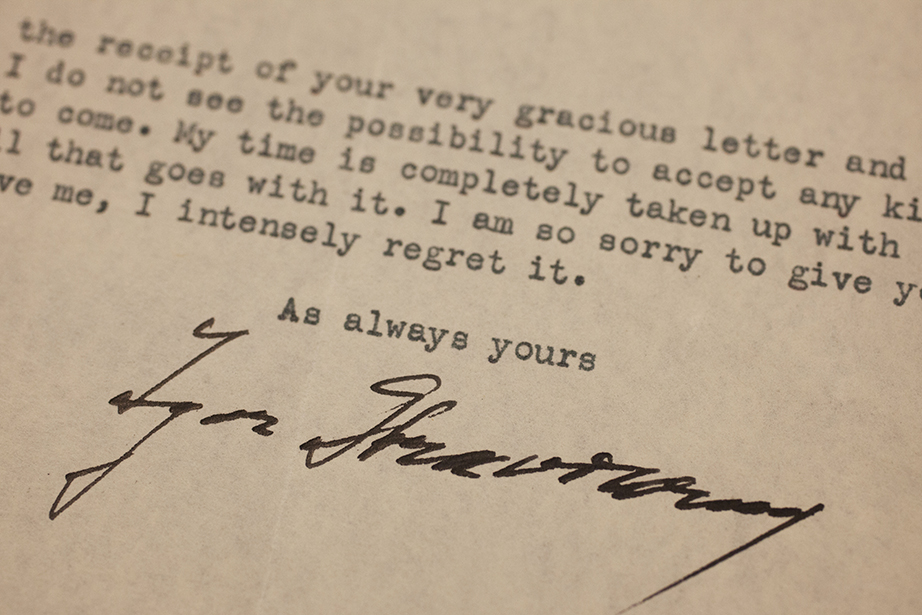

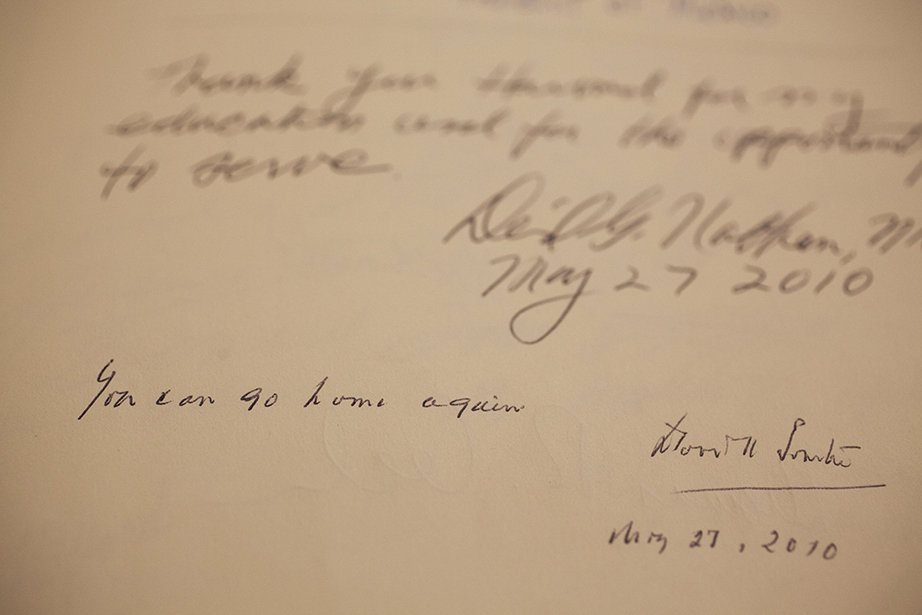

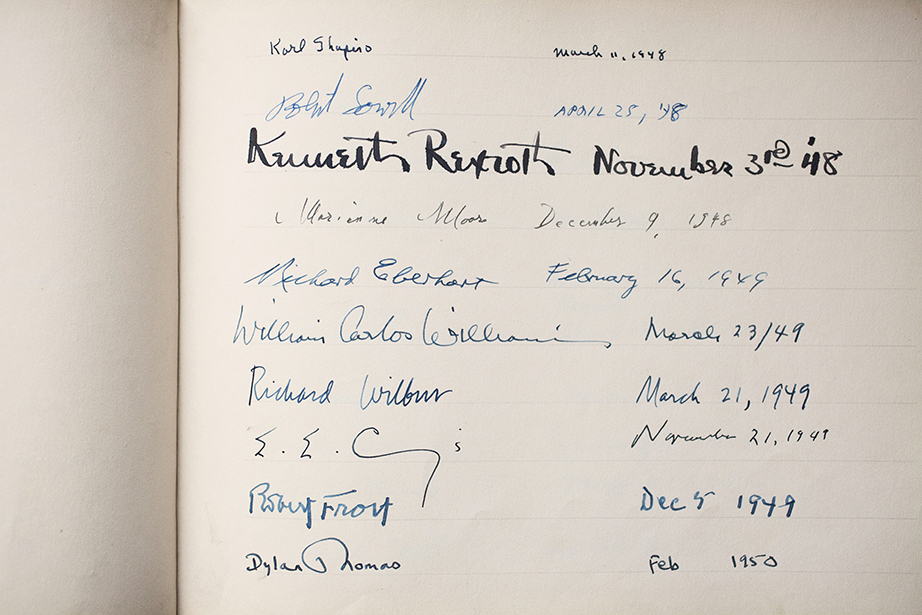

They are recorded in albums in places like Wadsworth House, a frequent stop for distinguished visitors, and the Department of English, which since 1939 has been collecting signatures from participants in its Morris Gray Lectures, including T.S. Eliot, Robert Penn Warren, Lillian Hellman, and Robert Frost.

“There’s a lot of power in a signature,” as well as the tremor of history, said special projects assistant Sean McCreery, who watches over the Gray album. When poets and writers add to it, he said, “no one skips a page. They’re colleagues, either in spirit or flesh.”

At the Harvard University Archives, there are millions of linear feet of correspondence and documents, often signed. “It’s not like we have a collection of signatures,” said archivist Barbara Meloni, who one November day lined up boxes of samples. “You will find them everywhere.”

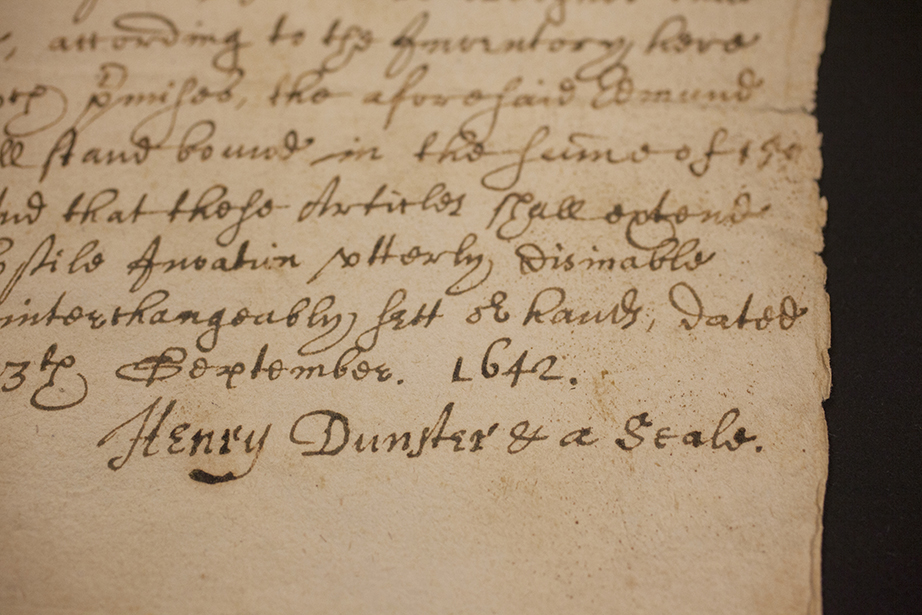

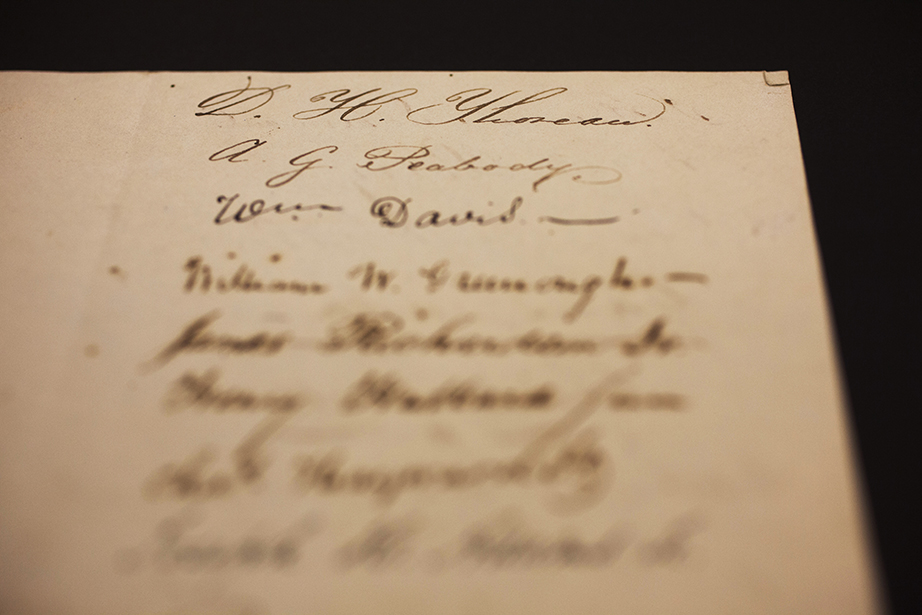

From 1642, on paper the color of heavy cream, the archives record the stately inked signature of Henry Dunster, Harvard’s first president. The archives also contain an early example of the most famous signature of colonial America, that of patriot leader John Hancock, then a College senior. (It appears on a 1754 letter scolding his sister Mary for not writing.)

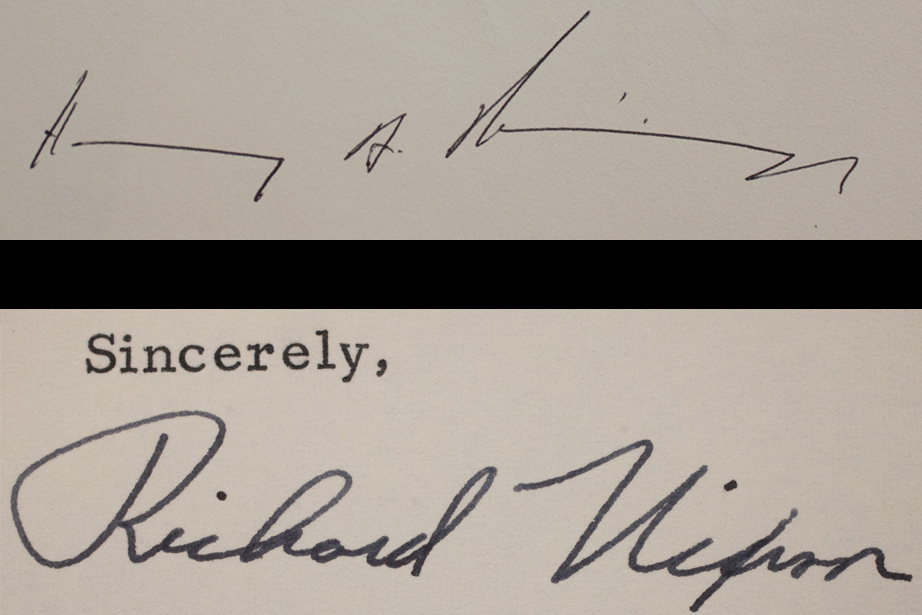

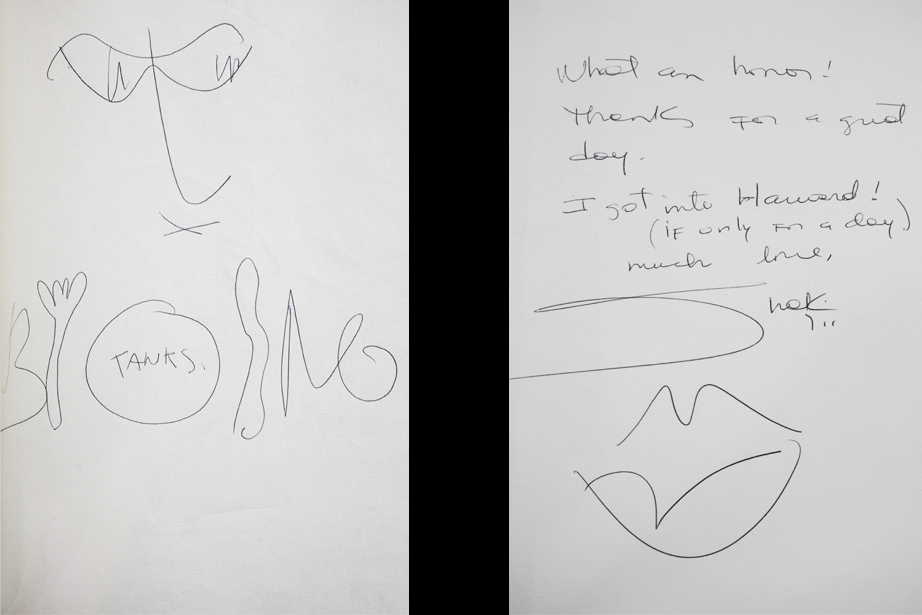

At Wadsworth House, University Marshal Jackie A. O’Neill keeps an eye on visitors’ albums dating back to 1979. (Many older ones are housed in the archives.) It’s a graphologist’s feast: Lawrence Fishburne’s signature is 6 inches tall, Henry Kissinger’s is inscrutable, and Bono’s includes a cartoon of a fork, knife, and plate. (One of his causes is world hunger.)

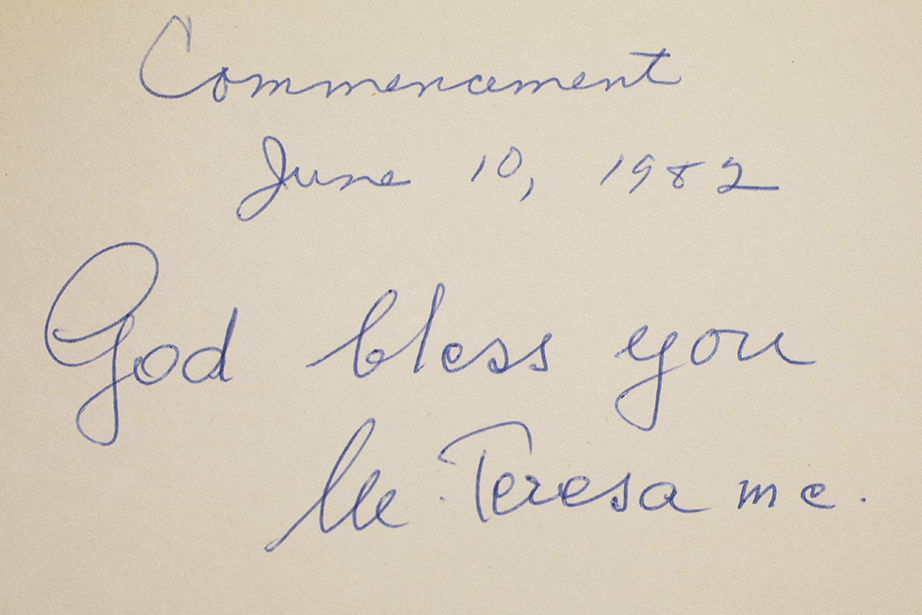

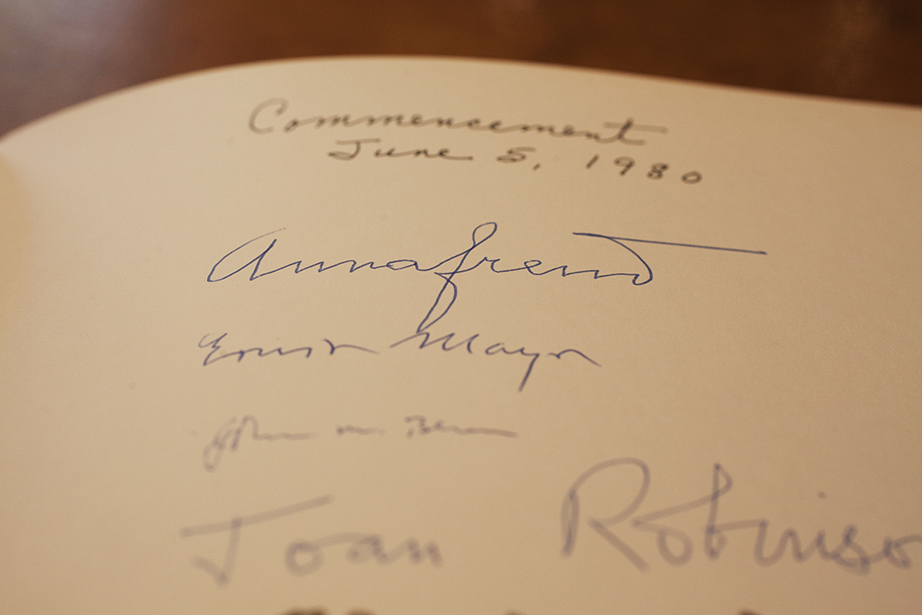

The Wadsworth albums include signatures from Jane Goodall, Ruby Dee, the Barenaked Ladies, Sinbad, and Mother Teresa (complete with a prefatory “God bless you”), as well as J.K. Rowling, Aga Khan, Gordon Brown, Doris Lessing, Queen Noor, and of that other Hancock, Herbie. The signature of James Gandolfini appears near that of Aung San Suu Kyi. Close by are Toni Morrison, Seamus Heaney, and Dan Aykroyd, who appended a few phony degrees. Anna Freud shares a page with Walter Cronkite. John Cheever included his address, as did Rodney Dangerfield.

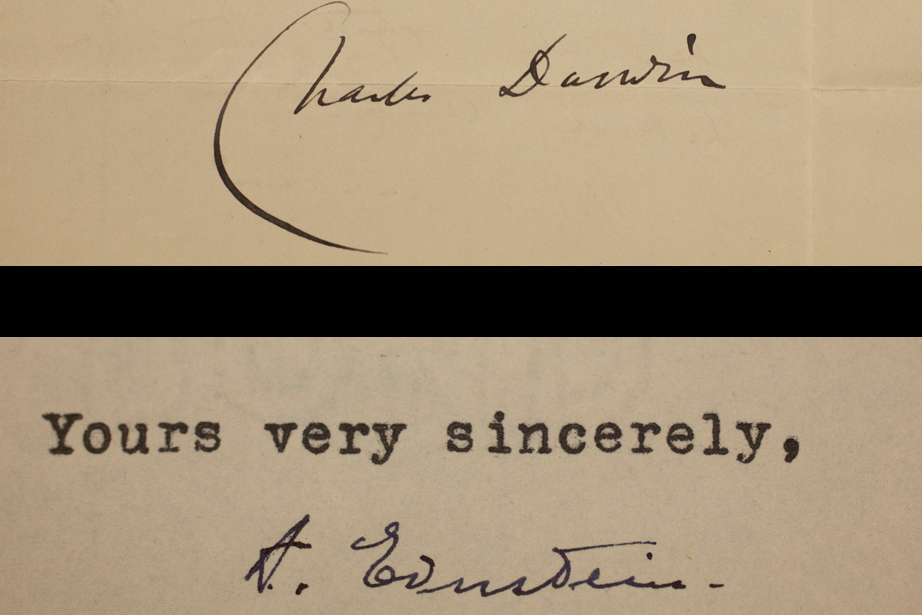

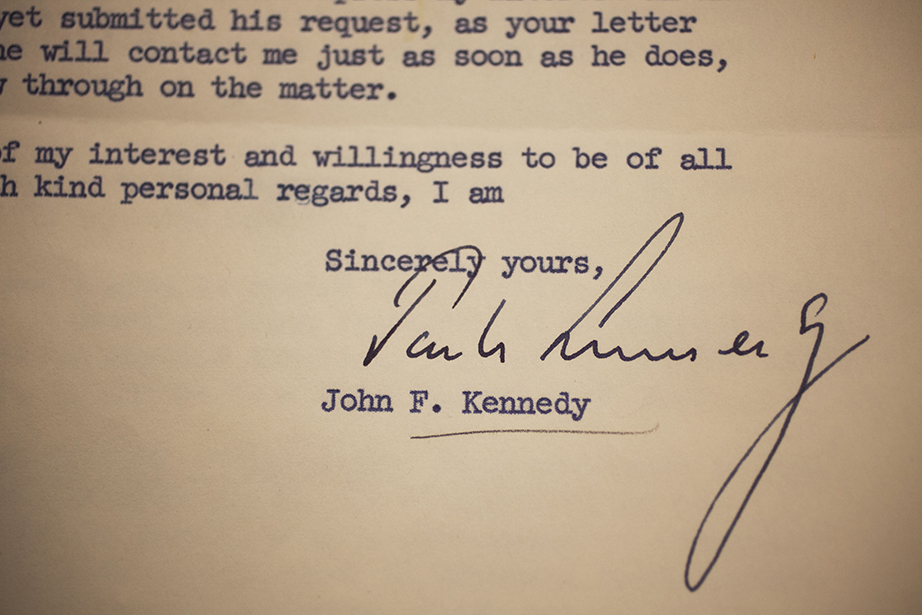

And there are surprises. In one 1915 Harvard class letter addressed to him, Robert Frost crosses out “Lee,” a middle name now lost to memory. In 1920, E.E. Cummings preferred “Edward Cummings.” Despite a brash reputation, Norman Mailer signed his name modestly small, as did Albert Einstein, whose influence has been immodestly large. W.H. Auden and Elizabeth Bishop had tiny signatures. Some signatures are impossible to decipher. Others are disarmingly clear. Richard Nixon signed in a cursive-clear, schoolboy hand.

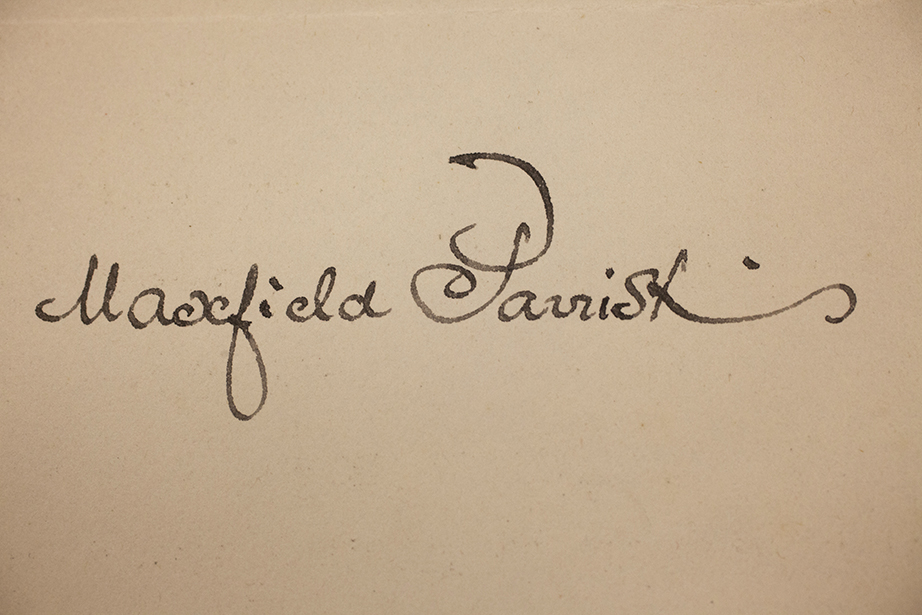

Both Andrew Wyeth and Maxfield Parrish signed bold and beautiful, as artists would. Nelson Mandela used just his last name, enough for a world that knows him well.

Every Harvard signature contains a story, O’Neill said, “a way of explaining the long history of this place.”