Sharyn Nolan (right) and Juliana Kuipers lead visitors through “Code Books to ‘Love Story’: Staff Selections from the Harvard University Archives’ Collections.” This inaugural staff exhibit, eccentric and surprising, is up through May 15.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Collectively peculiar

Ants, spikes, ‘squirrel food’ in staff-stocked Archives exhibit

In a quiet hallway outside the Harvard University Archives, it is jarring to encounter a giant black ant.

Well, OK: a picture of a giant black ant — glistening head, alitrunk, petiole, gaster. In the same glass case is a centuries-old wrought-iron gutter spike, retrieved from Massachusetts Hall after a fire 90 years ago. The spike, now displayed on a silk pillow, is the size of a bayonet, its head mashed flat by some colonial blacksmith.

Close by, also under glass, are a hand-written letter from John F. Kennedy ’40, an annotated almanac from 1775, protest photos from 1948, a first-edition Erich Segal novel, a vial of scent, and — on a 19th century memorial card — a weeping willow tree made of human hair.

“From Code Books to ‘Love Story’” is the inaugural exhibit in a new series at the Archives: periodic displays of the odd and the wonderful, all chosen by staffers. “We tried to pick stuff you wouldn’t expect,” said Juliana Kuipers, who otherwise processes new holdings to ready them for researchers.

Artifacts eccentric and exciting

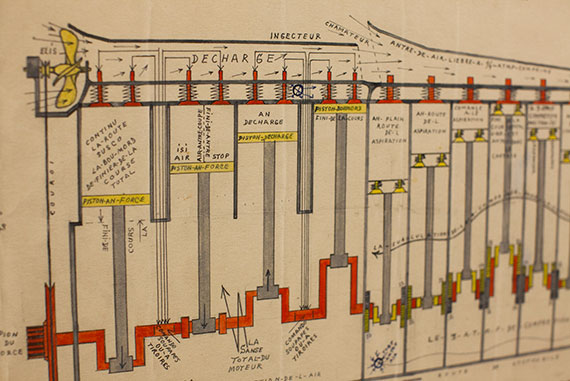

Plans for a purported perpetual-motion machine, from a Belgian inventor, were found in the papers of onetime Harvard astronomer Fred Whipple, who called such junk mail “squirrel food.” Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

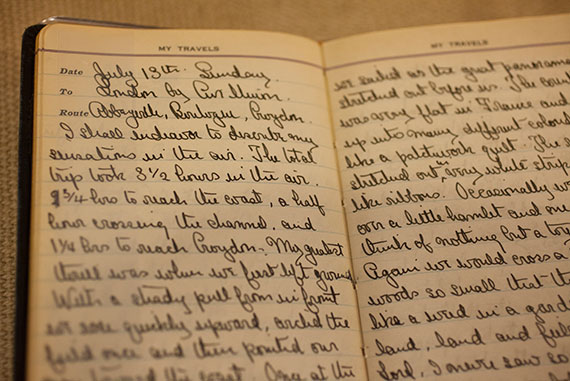

The 1924 European travel diary of William Worcester Cutler Jr. ’23, M.B.A. ’25, includes descriptions of his 3½-hour flight from France to England aboard a 12-seat passenger airliner.

Framed here is a “Memorial on the Death of C.S. Wheeler,” made in 1843 from the hair of the deceased, a history instructor at Harvard.

A wrought-iron gutter spike, circa 1720, recovered from Massachusetts Hall after a 1924 fire, was repurposed as a gift to a Harvard donor.

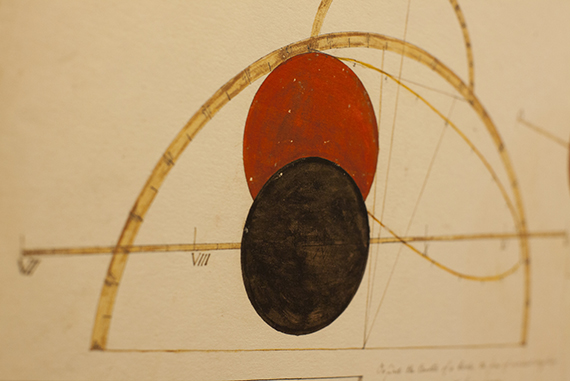

A detail from “Solar and Lunar Eclipse,” a mathematical thesis by Joel Giles, Class of 1829. It’s one of 406 such colorfully illustrated final papers in Harvard collections, most from between 1780 and 1830.

As for staff putting it all together: “Everybody has a different knowledge base at the Archives,” said Sharyn K. Nolan, whose usual roles are in records management — “on the dry side,” she admitted — and collection development. “This was a chance for all of us to pick something and shine.” Letters, photos, prints, and other artifacts are all part of the show, set to run through at least May 15.

Staffer Dominic Grandinetti, who has been processing the papers of the late Harvard astronomer Fred Whipple, chose items for one of the wall displays: illustrations of a perpetual motion machine, circa 1953-1954, from an unknown Belgian inventor. Whipple (1906-2004) not only discovered six comets, he received a lot of what he called “squirrel food” — that is, junk mail. It was in those files that the Belgian’s whimsical plans appeared, brightly colored and captioned in French. “Strange French,” said Kuipers.

Staff assistant Emily Tordo provided the other wall display, Mathematical Thesis No. 351, completed in 1829 by Joel Giles, who graduated from Harvard that year. (Four-hundred and six such theses have been digitized, spanning the 1780s to the 1830s.) “They were created to show competence in math,” said Nolan, but “they have become wonderful artworks.”

“Artworks” begins to describe the life’s labor of Segal ’58, represented in the exhibit by a fairly new acquisition: letters, photographs, scrapbooks, and books donated by his longtime friend Bernard Ackerman. Segal died in 2010 and his own papers are still with his family. But the Ackerman collection reveals a zany, joyously profane side to the man who wrote the bestselling “Love Story” (1970), as well as the script for animated Beatles film “Yellow Submarine” (1968).

Inches away, the exhibit zigs back to the 19th century, in an 1808 letter from John Tudor Cooper (Class of 1811) to his father. The long missive in spidery script paints a portrait of Harvard College 200 years ago. Every student at mealtime should zealously guard his food from ravenous classmates, Cooper wrote, lest “his pudding & meats will be gone.” He also tells of dining hall unrest. “That’s one of the things about this letter,” said Kuipers, who chose it. “Whenever you read anything from students, it’s nothing new.”

Complaints about food endure, but art made of human hair is safely a thing of the 19th century past. A card in remembrance of C.S. Wheeler, a Harvard history instructor who died in 1843, includes an illustration created largely from the deceased’s own hair. “Finer than the point of a pen,” Nolan said. “I know a lot of people find it creepy. But I find it touching.”

Kuipers, too, cited a particularly stirring choice: a sampler done in 1735 by 14-year-old Ann Thomas, whose presence in the Archives is still a mystery. (Her work, a woven poem, was found among the records of a Harvard librarian from the era.) “This really speaks to me,” said Kuipers. “At that time, women did not have a lot of voice.

In 1945, Kennedy had plenty of voice, in a comedic fundraising letter to classmates. He poked fun at why their first reunion was delayed. (World War II got in the way.) And he joshed that the class might buy land in Nevada for “a large underground cellar capable of holding 972 men of Harvard,” a dark joke inspired by the just-unleashed atomic bomb. The future president was funny, but with a Cold War edge. To reference assistant Pamela Hopkins, the letter is also a detective story about the handwriting. Is it really Kennedy’s?

Another handwriting puzzle arises in two letters written (in several hands) by Booker T. Washington to then-Dean of Harvard College LeBaron Russell Briggs. The first asked for money; the second thanked Briggs for his $10 tuition donation to Washington’s Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. Both are partly typed.

The ants are no puzzle — at least not to a young Edward O. Wilson, pictured in an exhibit photograph from 1959. With a crew cut and dressed in a sport coat and thin tie, the future Pellegrino University Professor and Pulitzer winner is hunched over specimens in a Harvard laboratory. To reference assistant Michelle Gachette, her “Invisible Invaders” entry evokes Wilson’s real science, but also an era of science fiction in which overgrown ants prowled movie screens in search of mayhem. The photo of the big black ant from Wilson’s lab, she wrote, “invades the senses.”

Speaking of, the past even gets a smell (we guess), from a display by archivist Barbara Meloni of “Sandalwood and Carrion,” a dissertation by James Andrew McHugh, PhD ’08 (now a book) that was submitted along with a boxed set of bottled scents. It’s the only item in Harvard’s entire library catalog assigned the search term “Perfume (scent),” said Nolan. “This was a challenge for us.”