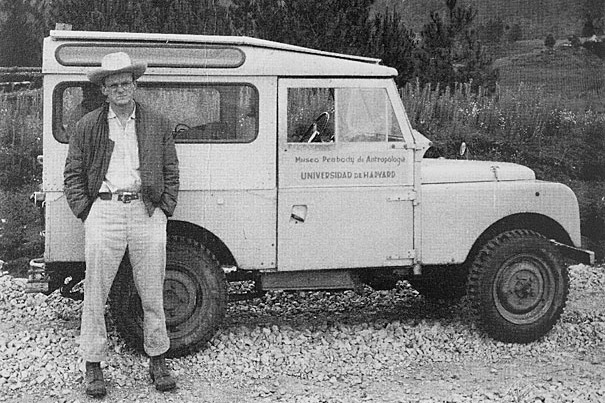

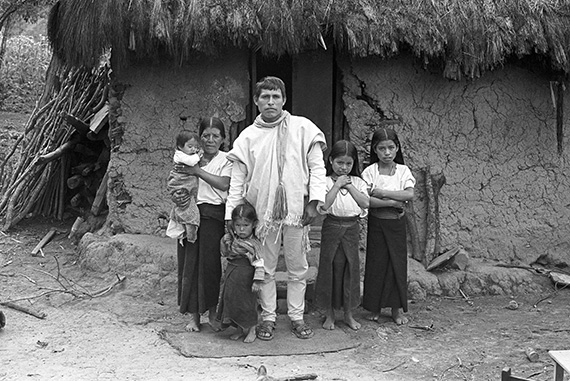

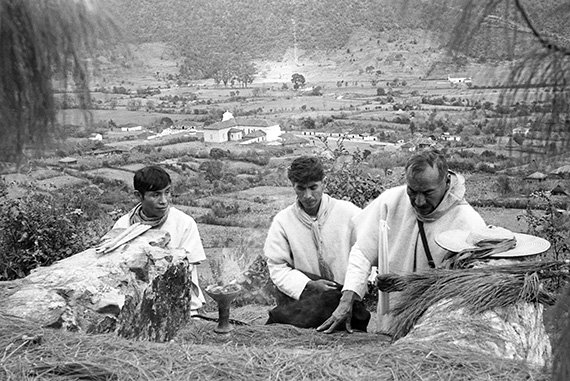

On the road in Chiapas in 1957 is Frank C. Miller, Ph.D. ’60, the first graduate student to join the Harvard Chiapas Project. (photo 1). Evon Z. Vogt (photo 2), dressed for fieldwork in Zinacantan in 1965, with his wife and collaborator Nan Vogt to his right and to her right future anthropologist Victoria Reifler Bricker, Ph.D. ’68. Summer 1960: The first undergraduates to join the Harvard Chiapas Project (photo 3). Seated in front, left and right, are future anthropologists (and spouses) Jane Fishburne Collier ’62 and George A. Collier ’63, Ph.D. ’68. Evon Vogt is second from left in the back row.

Courtesy of the Harvard Chiapas Project and the University of New Mexico Press

First model for Harvard in Mexico

Chiapas Project, led by charismatic Evon Vogt, studied Maya lifestyle, trained generations of anthropologists

The Hotel Geneve in Mexico City opened in 1907 and went on to host many firsts. It was the first hotel in Mexico with elevators, or a taxi service, or to serve sandwiches. And it was the hotel where, in 1957, Professor Evon Zartman Vogt met with Frank C. Miller, Ph.D. ’60, the first graduate student in what became the Harvard Chiapas Project.

The long-term ethnographic field study, which ran from 1957 to 1980, investigated how much Maya culture in the remote south changed under the pressures of modernity, and how much it stayed the same. The Maya had overlaid their ancient practices with a cunning veneer of modern influences, including the Roman Catholicism brought by the Spanish in the 1500s. Vogt and other anthropologists, eager to learn more, called this covert protection of old ways “cultural persistence.”

During the project’s 23 active years, Vogt — “Vogtie” to all his friends — helped to train two generations of Harvard anthropologists, inspired hundreds of publications, and established an extensive database on the rituals, economy, settlement patterns, and civic practices of the Maya in the rugged and stunning highlands of Chiapas.

“The Harvard Chiapas Project represents a high point of modernist anthropology,” said Miller, now 82, who retired from the University of Minnesota 12 years ago. Postmodern practitioners later altered the field, he said, skeptical that objectivity was even possible.

The project was also likely the University’s first sustained bi-national academic collaboration with Mexico. As such, it was the progenitor of today’s dozens of diverse collaborations covering disciplines from medicine and public health to art history and education.

“Vogt was very, very careful — thoughtful — in developing cordial relations with all kinds of people,” a strategy that in Mexico resulted in novel and deep associations with Mexican academics, said George A. Collier ’63, Ph.D. ’68, a retired anthropologist who taught at Stanford University.

At the heart of those relations was Mexico’s official aid agency for its Indian populations, the Instituto Nacional Indigenista (INI). In the summer of 1955, by invitation, Vogt attended a two-week conference in Mexico City on the work of the INI, followed by a week of touring rural INI centers with prominent Mexican anthropologists.

One center was in San Cristóbal de las Casas, the cultural capital of the Chiapas region. The town of about 7,600 people was nestled in a fertile valley bounded by a mountainous landscape of limestone and volcanic rock, more than 7,000 feet above sea level, and shaded by forests of pine and oak. The region was both colorful and poor. In his memoir, Vogt recalled town streets “full of Tzotzil and Tzeltal Maya Indians, carrying maize, wood, and charcoal with tumplines, headed for the market.”

Beyond the town, a Maya culture thrived, centered on farming and ritual practices in widely dispersed hamlets called municipos. The inhabitants of the countryside, in their woven palm hats and homemade high-backed sandals, embraced ancient practices. But they lived in social equilibrium with the more prosperous Ladino inhabitants of San Cristóbal.

Vogt was awestruck by the region’s beauty, by its unstudied, crisscrossing cultures, and by the idea of investigating how INI — with its mission to absorb Indians into a Mexican national culture — might alter Maya ways. He wrote later, “It was love at first sight.”

Chiapas: 1961-71

Bridegroom Pedro Pérez con Dios (with Francesca Cancian), 1961. Images courtesy of Frank Cancian and University of California, Irvine, UCI Libraries Special Collections and Archives

A view from Domingo de la Torre’s house, 1961.

Carrying firewood along the Pan American Highway near Navenchauc, 1971.

Mariano Pérez Jiménez’s family in front of their house, 1971.

5.Chiapas_a0072-44570×381

Carrying firewood along the Pan American Highway near Navenchauc, 1971.

6.Chiapas_a0086-09_570x381

Shaman Juan Vásquez Shulhol praying at a cross on the sacred mountain Kalvario, 1961.

Ritual drinks served during a fiesta, Dec. 31, 1961.

A moment captured during the Fiesta of San Sebastian, 1962.

Earlier Harvard forays

Harvard had connected scientifically to Mexico in smaller ways even earlier. Starting in 1879, freelance botanists collecting specimens for the University roamed the country seeking plant samples. In 1901, Alfred Tozzer, Class of 1900 and the future director of Harvard’s Peabody Museum, began several years of ethnographic fieldwork among the Maya before turning to Mexican archaeology.

“Tozzer was the Vogt of his generation,” said Harvard Mesoamerican archaeologist William L. Fash Jr., Charles P. Bowditch Professor of Central American and Mexican Archaeology and Ethnology. “He started out blazing, and did some amazing things,” and he trained many students, but his work in Mexico a century ago was less sustained than Vogt’s, said Fash. “Vogtie was unique in that respect. Nobody else spent 30 years in one place, and brought that many students.”

Tozzer had intended to sustain and broaden the Mexican connection. In 1914, he agreed to direct the International School of American Archaeology. But an escalation of the Mexican Revolution that year interrupted the idea. Tozzer gave up fieldwork, returned to Harvard, and “never got back [to Mexico] in a sustained way,” said Fash.

The Chiapas Project also became a kind of long-term experiment in the benefit of foreign travel for study. It began in an era when Harvard had not yet fully embraced the idea that study abroad was rocket fuel for students who wanted a sense of the world beyond books. And Vogt’s work in remote Chiapas was far from the European stops that for generations of the well-heeled were the gold standard of cultural education.

During those first two days in Mexico City in the summer of 1957, Vogt introduced Miller to a handful of Mexican anthropologists, planting the seeds of a cross-border collaboration that lasted for decades. He also taught his young charge, a Midwesterner who had been raised in a strict Methodist household, how to drink tequila: salt, salud!, shot (in one gulp), and then suck on a piece of lime. It was a Harvard seminar of sorts that “I recall with some pride,” Vogt wrote later in “Fieldwork Among the Maya” (1994), part memoir, part vehicle for praising former students, and part academic study.

“The problem was: Vogtie didn’t tell me how strong it was,” recalled Miller of his first drinking lesson. But Vogt’s bar-top seminar had meaning in the field, where potent alcohol was an entre into Maya culture. “They have ancient traditions of ritual drunkenness,” Miller said of the Maya, who drank a sugarcane concoction called posh.

The gregarious Vogt, a joyous New Mexico native and World War II veteran, loved to travel, talk, and dance. (His memorial service, in 2004, ended with a procession of friends snake-dancing behind a New Orleans-style band.)

“He had a sunny personality,” said Jorge I. Domínguez, who was a Harvard graduate student when he met Vogt. (Today he is the Antonio Madero Professor of the Study of Mexico, and Harvard’s vice provost for international affairs.) Along with that came a lack of pretension. “I don’t think I ever saw Vogtie with a briefcase,” said Domínguez. It was almost as if Vogt were saying, “If it’s good enough for Chiapas, it’s good enough for Harvard Yard.”

Developing students

Vogt’s warmth informed an attention to his students that is still legendary among veterans of the Chiapas project. “He was very unusual,” laid back and attentive, said Victoria Reifler Bricker, Ph.D. ’68, now a professor emerita at Tulane University. She had arrived at Harvard in 1962 as a graduate student eager to work with Vogt in Mexico. She recalled her surprise at his office in William James Hall, which was nearly empty. He had removed all the furniture except for the chairs — perches for visiting students — and a few bookcases. “He would sit and listen to what you would say,” added Bricker, still amazed.

Vogt “was a genius at developing students, an absolute genius,” said Frank Cancian, Ph.D. ’63, a retired anthropologist at the University of California at Irvine, who arrived in Chiapas as a graduate student in 1960 and was the project’s official photographer. He did fieldwork there until the early 1980s, wrote four related books, and still visits friends in Chiapas every summer. Vogt’s talent for tending his students, said Cancian, may be his truest legacy.

Next door to the office in William James Hall were voluminous files from the project, along with student papers and field notes. During his own nine months working in Chiapas, said Miller, Vogt insisted he send regular copies of his field notes. Miller tapped them out on an Olivetti portable typewriter. Vogt mailed back comments. “He was a wonderful mentor,” said Miller.

Starting in 1957, Vogt brought in at least one graduate student a year along for fieldwork in Chiapas, 42 by the project’s end. Most stayed for 12 months, but others returned for years. In 1960, Vogt began inviting at least six handpicked undergraduates to join in summer fieldwork each year. Most were from Harvard, though others came from Columbia, Cornell, the University of Illinois, Smith, and elsewhere.

Jonathan P. Hiatt ’70 was a social studies concentrator in those days and went on to law school. (Today he’s executive assistant to the president at the AFL-CIO.) Not sure what direction his life would take, Hiatt joined the Chiapas project in the summer of 1968 after spending the previous summer in Peru. Anthropology was not to be his career path, but the project “is how I learned Spanish,” he said, a valuable skill when he became a labor attorney. That summer also baited the hook for Hiatt’s lifelong interest in Latin America.

About 120 undergraduates summered in Chiapas from 1960 through 1980. They went on to write, teach, practice law or medicine, make films, study art history, and pursue careers in anthropology. Of the first Chiapas undergraduates, in 1960, all six went on to be anthropologists. Two of them even married, the first of a handful of such unions.

Collier is married to Jane Fishburne Collier ’62. Both are retired from Stanford, but during their careers they continued, in part, to study Chiapas. George Collier’s “Basta!” (1994) is an origin study of the Zapatista rebellion. Jane Collier, who earned her doctorate at Tulane, wrote “Law and Social Change in Zinacantán” (1973), based on a project started with Vogt. She also went on to be a pioneer in anthropological feminist theory.

“There were very few projects of any kind … that developed quite the scope” of the Chiapas Project, said George Collier. Vogt brought in students and practitioners from other disciplines. Summertime sessions critiquing field research unfolded “regardless of rank or status.”

Hiatt recalled the same egalitarian feeling permeating the Chiapas experience for students, “whether they were anthropologists,” he said with a laugh, “or freeloaders like me.”

Equal opportunities

Vogt and his wife, Catherine (“Nan”) — who was his co-researcher, editor, and field collaborator — brought their four children to Chiapas every summer, sometimes after freewheeling, cross-country drives. Miller fondly remembered Nan for her contributions to Vogt’s scholarship, for being half-responsible for hosting “the best parties anywhere,” and for being “a den mother for all us graduate students.”

The egalitarian spirit of the project extended to gender as well. In 1960, two of the six undergraduates invited were women. Disregarding the gender norms in academic arenas back then, said Jane Collier, “Vogtie was very open to women.”

She mentioned two for whom Vogt opened professional doors. Bricker, author of the celebrated “The Indian Christ, The Indian King” (1981), became an expert in Mayan languages, Maya hieroglyphs, and archaeological clues to Precolumbian Maya astronomy. And Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo ’65, Ph.D. ’72, was well into a brilliant career at Stanford when she was killed in a 1981 field research accident.

Tolerance, agreed Miller, “was great training.” That was built into Vogt, he said, during his boyhood on a New Mexico sheep ranch where neighbors represented a diversity of languages and cultures. There were Zuni and Navajo Indians, Mexican-Americans, and Mormons, who were his earliest schoolteachers. Growing up, Vogt said there was a “rural microcosm of the United Nations lying within 40 miles of the Vogt ranch.”

To earn money to attend the University of Chicago, Vogt worked as a gold miner and a park ranger. Smitten with landscapes, he majored in geography, a first love that later contributed to his multi-university work, from 1963 to 1969, using aerial photography to study settlement and land-use patterns. These were abiding puzzles to anthropologists hampered by weather and the difficulties of rural census-taking.

In addition to his academic drive, Vogt remained at heart an affable, expansive Westerner who was not conventionally ambitious, said Jane Collier, but instead was “open to people of diverse backgrounds.” Miller remembered Vogt the same way. “He didn’t have any of the Harvard faculty pretensions. He was a down-to-earth ranch boy,” he said. “That was a part of him. He held onto it his whole life.”

Six times between 1965 and 1973, he brought three native Tzotzil speakers to Harvard. These “informants,” as Vogt called them, lent reality to the spring-semester language courses in Tzotzil that by then were required for summer fieldwork. One of Mexico’s 29 spoken Mayan languages, it was the lingua franca of the Chiapas highlands.

Getting good fieldwork

Over 12 years, by Vogt’s own account, the basic requirements for anthropology fieldwork came into focus. It had to be over the long term; it required multiple observers from a variety of disciplines; it required local language skills; and it required geographical focus. The first focus was the town of Zinacantán, which in 1960 had a population of fewer than 400. A neighboring community, Chamula, was added later, “for comparison and contrast,” said Vogt.

Good fieldwork required living with locals whenever possible, and Vogt arranged it. Students spent four days or more boarding with Maya families in Zinacantán or Chamula. Hiatt remembered using sleeping bags, and eating meals of beans, mustard greens, tortillas, and “sometimes an egg.” Then came a couple of days in San Cristóbal to get a shower and type up field notes. All in all, said Hiatt, “it was pretty spectacular.”

The project’s results were proving pretty spectacular, too. In 1969 Vogt published “Zinacantán: A Maya Community in the Highlands of Chiapas,” a comprehensive ethnography that won writing prizes both at Harvard and in Mexico.

The book — “a benchmark in cross-cultural studies,” one critic called it — was a synthesis of Vogt’s own work and his students’. That collaborative authorship, Cancian said, made it unique among the era’s “grand monographs,” an aspirational anthropological format usually written by just one person.

“It’s a richer book than any other I know about,” said Cancian. It was also among the last publications in the classic monograph format. Fash agreed that the days of voluminous field reporting are gone. “Big description is out,” he said.

But in 1977, results from the project seemed even more significant. A 1957-1977 bibliography assembled by Vogt mentioned hundreds of articles, 33 undergraduate honors theses, 27 monographs or books, 21 Ph.D. dissertations, two novels, and a documentary film.

The project created a lot of data, too, “grist for the anthropologist’s mill,” Vogt said in a 1995 speech, that could be mined for years. “Theories come and go,” he added, “but good data are timeless.”

Vogt’s voluminous work is a “remarkable legacy,” said Fash, but underappreciated in today’s “activist anthropology.” “Everybody’s out trying to change the world, whereas Vogtie was trying to do a natural history of Maya thought.”

Grasping Maya rituals

Vogt’s long-term study of the Tzotzil Maya, from 1957 to 1992, lasted longer than the project. But he had come to believe strongly that field projects in anthropology required at least 20 continuous years in order to be useful. The duration of his attention to one culture in one corner of rural Mexico made gaining local trust possible. And the duration created subtleties impossible to understand in the short term, such as Vogt’s grasp of rituals and religion.

In 1958, Vogt co-authored a book with William A. Lessa, “Reader in Comparative Religion: An Anthropological Approach,” which is still in print and used in classrooms. Forty years later he wrote a book chapter on Zinacanteco rituals. In between, Vogt taught a celebrated Harvard course in comparative religion and produced his masterwork, “Tortillas for the Gods: A Symbolic Analysis of Zinacanteco Rituals” (1976).

Being in the field long-term also revealed at least one idea that Vogt derived from the Maya proclivity for propelling the spiritual experience with rum. About a decade before he died, in a lecture at the University of California, Berkeley, he recounted an experience at the fiesta of San Lorenzo in 1959. For reasons of Zinacanteco etiquette, Vogt was required to drink rum early that morning. He then stumbled outside and suddenly realized that the towering sacred mountain looming nearby resembled the steep-sided Maya pyramids to the south.

Alcohol was the “trigger mechanism” for his insight, Vogt said. He introduced his hypothesis the following year at a conference in Paris: that the steep mountains of Chiapas, riven with sacred caves and altar-like clearings, prefigured the mountain-like ceremonial sites of those pyramids, with their tombs and altars. Twenty-five years later, archeological evidence confirmed the truth of his insight.

There yesterday, gone today

Today, said Fash, anything like the Chiapas Project would be impossible. “Those times are gone,” he said, and Chiapas itself is beset on all sides by “global influences.”

True, said Cancian, the Chiapas of 50 years ago is gone. The population of San Cristóbal has quadrupled, to about 30,000. A thriving transportation industry helps prop up the prosperous hothouse flower farms that have displaced traditional plots. Where once “there were a few bottles of Pepsi around,” said Cancian, there are Pepsi and Coca Cola distributors.

But has modern life made the Maya fade away? “I don’t know,” said Cancian doubtfully. “They’re modern now, but they’re still different than the people around them.”

Add in one more factor that would make Vogt’s project impossible today, said Jane Collier: “money, money, money.” Back then, Vogt sought and received grants from national foundations for his work. Today, said Miller, such funding “would be inconceivable.” Even Vogt’s funding eventually faded. For the last four years of the Harvard Chiapas Project, he used his own money.

On the heels of the Vietnam War came Marxist critics of Western anthropology. In Mexico, they took special aim at the Chiapas Project. By the 1980s there was growing critical pressure from postmodernist anthropologists, who saw the discipline as a humanities practice devoted to narrative and not a social science practice driven by quantitative data. Today, said Miller, “it’s a dramatically different field.”

In the end, Vogt recalled, “We came like the rains, every summer. We did no harm, but some good!”

And one legacy was that flowers sprouted from the Harvard Chiapas Project, in the many academic ties that have developed between the University and Mexico in recent years.

“The Harvard-Mexico collaboration was reinforced at Vogtie’s retirement party” in 1989 at the Harvard Club of Boston, recalled Miller in an email. “I took a break from dancing to mariachi music and went out into the hall, only to encounter two Mexican lawyers.” They had been drawn by sounds from their distant native land, jarringly present at a Harvard event. Such music, in such a place, said Miller, “they never expected to hear.”