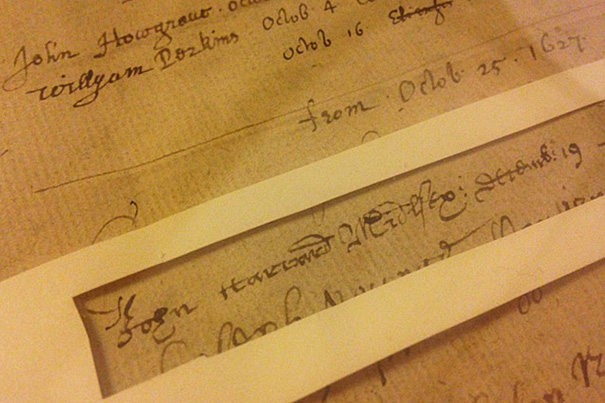

While at the University of Cambridge, Harvard President Drew Faust examined a 17th-century registration book bearing the only known signature of a 1624 Emmanuel College matriculant named John Harvard.

Photo courtesy of University of Cambridge

In the Civil War, roots of carnage

At University of Cambridge, Faust offers parallels between that conflict and World War I

World War I, whose guns opened fire just over a century ago, is often called the first modern large-scale war, when traditional fighting tactics gave way to the murderous innovations of industrial weaponry, including poison gas, tanks, long-range artillery, and armed aircraft. But Harvard President Drew Faust on Monday offered a different narrative.

Instead, she said, it was a conflict a half century earlier and an ocean away, the American Civil War, that first pitted the infantry charge and other traditional tactics against rapidly modernizing weaponry. It was the Civil War, whose increasingly sophisticated gunfire and artillery sent men desperately digging into the earth for shelter, that pioneered trench warfare, she said. It was the Civil War, and General William Tecumseh Sherman’s March to the Sea, that expanded the fight beyond battlefields to civilians supporting the war. It was the Civil War — still the bloodiest in U.S. history — whose 750,000 dead showed the world the carnage that modern weapons could produce, and prompted governments to honor and bury the fallen in national cemeteries.

In England, Faust delivered the prestigious Sir Robert Rede Lecture at the University of Cambridge’s historic Senate House. The hourlong speech drew a crowd of roughly 150 people — including more than a dozen Harvard alumni studying or teaching at Cambridge — to the neoclassical stone building completed in 1730 as a formal ceremonial venue.

In an introduction, Cambridge Vice-Chancellor Sir Leszek Borysiewicz praised the “historic connection and active links” between Harvard and Cambridge’s Emmanuel College, where Faust is an honorary fellow. One historic connection between the institutions was on display at the post-lecture reception: a 17th century registration book bearing the only known signature of a 1624 Emmanuel College matriculant named John Harvard.

The talk, the university’s oldest named lecture, was endowed in 1524 by Rede’s estate. Previous Rede lecturers have included English biologist and early evolution supporter Thomas Henry Huxley in 1883, Irish President Mary Robinson in 1996, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao in 2009, and Nobel Prize-winning scientist and National Cancer Institute Director Harold Varmus in 2011.

Faust, the Lincoln Professor of History, is an authority on the Civil War. Her 2008 book, “This Republic of Suffering,” examined the society-wide impact of the war’s dead and was a Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award finalist.

In her talk, titled “Two Wars and the Long Twentieth Century: The United States 1861-65; Britain, 1914-18,” Faust drew parallels between the impact of the American Civil War on the United States and World War I on the United Kingdom. Each took a similar toll in lives: 750,000 in the Civil War versus 722,785 British in World War I. Each drew the populace into an all-out effort that prompted new ideas of citizenship and freedoms, for American blacks after the Civil War, and in expanded suffrage in Britain after World War I.

Ideology played a role in both conflicts, Faust said, with nationalism and patriotism spurring enlistment. Further, when that failed to produce the needed numbers, each country embraced conscription for the first time.

The American Civil War, Faust said, kicked off what could be looked at as “the long 20th Century,” inaugurating an era of strife marked not just by innovations in the tools of war, but also in newly massive “citizen” armies and advances in communications, media, and transportation.

With all that firepower in play, those massive citizen armies produced massive numbers of dead. But those dead continued to change society even after their burials. Their sacrifices were honored in both nations, where national military cemeteries were created. In the United States, a major effort was undertaken to locate those buried on the battlefields, identify them, and rebury them properly. British cemeteries from World War I mingled those from different strata of England’s class-conscious society, holding firm to the principle that in death all are equal. The sacrifice of the ordinary soldier and the unknown dead was further honored by the burial of a single unidentified British soldier among the royalty in Westminster Abbey.

The understanding and acceptance of the widespread sacrifice demanded by each conflict — including by women, who manned factories and farms — gave power to movements to further democratize each society afterward. The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed voting rights to black men after the Civil War. In Britain after World War I, new laws tripled the number of voters, including women for the first time.

“I believe that the characteristics of modernity gripped us well before 1914, as the American Civil War introduced us to a new conception of carnage that human beings could and would inflict upon one another,” Faust said. “Humans had in one sense become cogs in the machinery of an increasingly industrialized warfare. Yet they were at the same time newly citizens and selves with bodies and names that had rights in life and in death.”

Faust reflected on the human capacity to ignore or forget even devastation described by witnesses as unforgettable. Europe’s military leaders missed any lessons the Civil War might have taught, despite evidence that the conflict represented a new, deadlier kind of strife.

“After Gettysburg, there should not have had to be the first day of the Somme,” Faust said, referring to the bloodiest day in British Army history, which left some 60,000 dead, wounded, or missing.

Despite the assurances of remembrance that came after World War I, World War II followed short years later. Henry James, whose brother was injured in the Civil War and who moved to London and lived long enough to witness the early years of World War I, echoed the disillusionment of many when he wrote that, “Reality is a world … capable of this.”

Viewed in hindsight, the wars offer parallels and contradictions that remain challenges today, Faust said.

“We still live amidst these contradictions and these ironies; we still struggle with the challenges to belief and meaning that these wars represented; we still seek to understand what it might have been like to be one of those who fought or those who died,” Faust said. “These wars have in profound ways defined us and our age.”